Greg Abbott

Greg Abbott | |

|---|---|

Abbott in 2015 | |

| 48th Governor of Texas | |

| Assumed office January 20, 2015 | |

| Lieutenant | Dan Patrick |

| Preceded by | Rick Perry |

| Chair of the Republican Governors Association | |

| In office November 21, 2019 – December 9, 2020 | |

| Preceded by | Pete Ricketts |

| Succeeded by | Doug Ducey |

| 50th Attorney General of Texas | |

| In office December 2, 2002 – January 5, 2015 | |

| Governor | Rick Perry |

| Preceded by | John Cornyn |

| Succeeded by | Ken Paxton |

| Justice of the Supreme Court of Texas | |

| In office January 2, 1996 – June 6, 2001[1] | |

| Appointed by | George W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Jack Hightower |

| Succeeded by | Xavier Rodriguez |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Gregory Wayne Abbott November 13, 1957 Wichita Falls, Texas, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 1 |

| Residence | Governor's Mansion |

| Education | University of Texas at Austin (BBA) Vanderbilt University (JD) |

| Signature | |

Gregory Wayne Abbott (born November 13, 1957) is an American politician, attorney, and jurist serving as the 48th governor of Texas since 2015. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the 50th attorney general of Texas from 2002 to 2015 and as a justice of the Texas Supreme Court from 1996 to 2001.

Abbott was the third Republican to serve as attorney general of Texas since the Reconstruction era. He was elected to that office with 57% of the vote in 2002 and reelected with 60% in 2006 and 64% in 2010, becoming the longest-serving Texas attorney general in state history, with 12 years of service. Before becoming attorney general, Abbott was a justice of the Texas Supreme Court, a position to which he was appointed in 1995 by then-governor George W. Bush. Abbott won a full term in 1998 with 60% of the vote. As attorney general, he successfully advocated for the Texas State Capitol to display the Ten Commandments in the 2005 U.S. Supreme Court case Van Orden v. Perry, and unsuccessfully defended the state's ban on same-sex marriage. He was involved in numerous lawsuits against the Barack Obama administration, seeking to invalidate the Affordable Care Act and the administration's environmental regulations.

Elected in 2014, Abbott is the first Texas governor and third governor of a U.S. state to use a wheelchair, the others being Franklin D. Roosevelt and George Wallace. As governor, Abbott supported the Donald Trump administration and has promoted a conservative agenda, including measures against abortion such as the Texas Heartbeat Act, lenient gun laws, opposition to illegal immigration, support for law enforcement funding, and election reform. In response to the power crisis following a February 2021 winter storm, Abbott called for reforms to Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) and signed a bill requiring power plant weatherization. During the COVID-19 pandemic in Texas, Abbott opposed implementing face mask and vaccine mandates, while blocking local governments, businesses, and other organizations from implementing their own. He has also made a priority of fighting illegal immigration, starting Operation Lone Star in 2021.

Early life, education, and legal career

Abbott was born on November 13, 1957, in Wichita Falls, Texas, of English descent.[2] His mother, Doris Lechristia Jacks Abbott, was a housewife and his father, Calvin Rodger Abbott, was a stockbroker and insurance agent.[3][4] When he was six years old, they moved to Longview; the family lived there for six years.[3] When he was 12, Abbott's family moved to Duncanville. In his sophomore year in high school, his father died of a heart attack; his mother went to work in a real estate office.[3] Abbott graduated from Duncanville High School,[5] where he was on the track team,[6] in the National Honor Society and was voted "Most Likely to Succeed".[6]

In 1981, Abbott earned a Bachelor of Business Administration in finance from the University of Texas at Austin, where he was a member of the Delta Tau Delta fraternity and the Young Republicans Club. He met his wife, Cecilia Phalen, while attending UT Austin.[3] The two married in 1981.[7] In 1984, he earned his Juris Doctor degree from the Vanderbilt University Law School.[3]

Abbott went into private practice, working for Butler and Binion, LLP between 1984 and 1992.[8]

Judicial career

Abbott's judicial career began in Houston, where he served as a state trial judge in the 129th District Court for three years.[8] Then-Governor George W. Bush appointed Abbott to the Texas Supreme Court; he was then twice elected to the state's highest civil court—in 1996 (two-year term) and in 1998 (six-year term). In 1996, Abbott had no Democratic opponent but was challenged by Libertarian John B. Hawley of Dallas. Abbott defeated Hawley, 84% to 16%.[9] In 1998, Abbott defeated Democrat David Van Os, 60% to 40%.[10]

In 2001, after resigning from the Supreme Court, Abbott returned to private practice and worked for Bracewell & Giuliani LLC.[11] He was also an adjunct professor at University of Texas School of Law.[12]

Attorney General of Texas (2002–2015)

2002 election

Abbott resigned from the Texas Supreme Court in 2001 to run for lieutenant governor of Texas.[3] He had been campaigning for several months when the previous attorney general, John Cornyn, vacated the post to run for the U.S. Senate.[3] Abbott then switched his campaign to the open attorney general's position in 2002. He defeated the Democratic nominee, former Austin mayor and former state senator[13] Kirk Watson, 57% to 41%.[14] Abbott was sworn in on December 2, 2002, following Cornyn's election to the Senate.[citation needed]

Tenure

Abbott expanded the attorney general's office's law enforcement division from about 30 people to more than 100.[3] He also created a new division, the Fugitive Unit, to track down convicted sex offenders in violation of their paroles or probations.[3]

In 2003, Abbott supported the Texas Legislature's move to cap non-economic damages for medical malpractice cases at $250,000, with no built-in increases for rising cost of living.[15]

In a 2013 speech to fellow Republicans, when asked what his job entails, Abbott said: "I go into the office in the morning, I sue Barack Obama, and then I go home."[16] Abbott filed 31 lawsuits against the Obama administration,[17] including suits against the Environmental Protection Agency; the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, including challenges to the Affordable Care Act ("Obamacare"); and the U.S. Department of Education, among many others.[3] According to The Wall Street Journal, from Abbott's tenure as attorney general through his first term as governor, Texas sued the Obama administration at least 44 times, more than any other state over the same period; court challenges included carbon-emission standards, health-care reform, transgender rights, and others.[18] The Dallas Morning News compared Abbott to Scott Pruitt, noting that both attorneys general had repeatedly sued the federal government over its environmental regulations.[19] The Houston Chronicle noted that Abbott "led the charge against Obama-era climate regulations".[20]

Abbott has said that the state must not release Tier II Chemical Inventory Reports for security reasons, but that Texans "can ask every facility whether they have chemicals or not".[21] Koch Industries has denied that its contributions to Abbott's campaign had anything to do with his ruling against releasing the safety information.[22]

In March 2014, Abbott filed a motion to intervene on behalf of Baylor Scott & White Medical Center – Plano in three federal lawsuits against the hospital, brought by patients who alleged that the hospital allowed Christopher Duntsch to perform neurosurgery despite knowing that he was a dangerous physician.[23] Abbott cited the Texas legislature's cap on malpractice cases and the statute's removal of the term "gross negligence" from the definition of legal malice as reasons for defending Baylor.[24]

In the late 2000s, Abbott established a unit in the attorney general's office to pursue voter-fraud prosecutions, using a $1.4 million federal grant; the unit prosecuted a few dozen cases, resulting "in small fines and little or no jail time".[25] The office found no large-scale fraud that could change the outcome of any election.[25]

Lawsuit against Sony BMG

In late 2005, Abbott sued Sony BMG.[26][27] Texas was the first state in the nation to bring legal action against Sony BMG for illegal spyware.[26][27] The suit is also the first filed under the state's spyware law of 2005.[26][27] It alleges the company surreptitiously installed the spyware on millions of compact music discs (CDs) that consumers inserted into their computers when they played the CDs, which can compromise the systems.[27][28] On December 21, 2005, Abbott added new allegations to his lawsuit against Sony-BMG. He said the MediaMax copy protection technology violated Texas's spyware and deceptive trade practices laws.[26][29] Sony-BMG offered consumers a licensing agreement when they bought CDs and played them on their computers;[26][29] in the lawsuit, brought under the Consumer Protection Against Computer Spyware Act of 2005 and other laws, Abbott alleged that even if consumers rejected that agreement, spyware was secretly installed on their computers, posing security risks for music buyers and deceiving Texas purchasers.[26][29][30] Sony settled the Texas lawsuit, as well as a similar suit brought by California's attorney general, for $1.5 million.[31]

Separation of church and state

In March 2005, Abbott delivered oral argument before the United States Supreme Court on behalf of Texas, defending a Ten Commandments monument on grounds of the Texas State Capitol. Thousands of similar monuments were donated to cities and towns across the nation by the Fraternal Order of Eagles, who were inspired by the Cecil B. DeMille film The Ten Commandments (1956) in following years.[32] In his deposition, Abbott said, "The Ten Commandments are a historically recognized system of law."[33] The Supreme Court held in a 5–4 decision that the Texas display did not violate the First Amendment's Establishment Clause and was constitutional.[34] After Abbott's oral arguments in Van Orden v. Perry, Justice John Paul Stevens commented upon Abbott's performance while in a wheelchair, "I want to thank you [...] for demonstrating that it's not necessary to stand at the lectern in order to do a fine job."[6]

Firearms

As attorney general, Abbott opposed gun control legislation. In 2013, he criticized legislation enacted by New York State strengthening its gun regulation laws by expanding an assault weapons ban and creating a high-capacity magazine ban; he also said he would sue if Congress enacted a new gun-control bill.[35] After the law passed, Abbott's political campaign placed Internet ads to users with Albany and Manhattan ZIP codes suggesting that New York gun owners should move to Texas. One ad read, "Is Gov. Cuomo looking to take your guns?", and the other read, "Wanted: Law abiding New York gun owners looking for lower taxes and greater opportunity." The ads linked to a letter on Facebook in which Abbott wrote that such a move would enable citizens "to keep more of what you earn and use some of that extra money to buy more ammo".[36]

In February 2014, Abbott argued against a lawsuit brought by the National Rifle Association of America (NRA) to allow more people access to concealed carry of firearms, as he felt this would disrupt public safety.[37]

Tort reform

Abbott backed legislation in Texas to limit "punitive damages stemming from noneconomic losses" and "noneconomic damages in medical malpractice cases" at $750,000 and $250,000, respectively.[38] While the settlement in his own paralysis case was a "nonmedical liability lawsuit", which remains uncapped, Abbott has faced criticism, generally from Democrats who oppose the Republican-backed lawsuit curbs, for "tilt[ing] the judicial scales toward civil defendants."[38]

Support for ban on sex toys

As attorney general, Abbott unsuccessfully defended Texas's ban on sex toys.[39] He said Texas had a legitimate interest in "discouraging prurient interests in autonomous sex and the pursuit of sexual gratification unrelated to procreation."[39]

Opposition to same-sex marriage

As attorney general, Abbott defended the state's ban on same-sex marriage from a constitutional challenge.[40] In 2014, he argued in court that Texas should be allowed to prohibit same-sex marriage because LGBT individuals cannot procreate. He said that as "same-sex relationships do not naturally produce children, recognizing same-sex marriage does not further these goals to the same extent that recognizing opposite-sex marriage does."[39] He also argued that gay people are still free to marry, saying they are "as free to marry an opposite-sex spouse as anyone else".[39] He suggested that same-sex marriage led to a slippery slope in which "any conduct that has been traditionally prohibited can become a constitutional right simply by redefining it at a higher level of abstraction."[39]

In 2016, Abbott urged the Texas Supreme Court to limit the impact of the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 case that held that the 14th Amendment requires all states to recognize same-sex marriages and made same-sex couples eligible for state and federal benefits tied to marriage, including the right to be listed on a birth certificate and the right to adopt.[41][42]

2006 election

In the November 7, 2006, general election, Abbott was challenged by civil rights attorney David Van Os, who had been his Democratic opponent in the 1998 election for state Supreme Court. He was reelected to a second term with 60% to Van Os's 37%.[43]

2010 election

Abbott ran for a third term in 2010. He defeated the Democratic nominee, attorney Barbara Ann Radnofsky, with 64% of the vote to her 34%.[44] He was the longest-serving Texas attorney general in Texas history.[45]

In July 2013, the Houston Chronicle alleged improper ties and oversight between many of Abbott's largest donors and the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas, of which he was a director.[46]

Gubernatorial elections

2014 election

- >90%

- 80–90%

- 70–80%

- 60–70%

- 50–60%

- 40–50%

- 70–80%

- 60–70%

- 50–60%

- 40–50%

In July 2013, shortly after Governor Rick Perry announced that he would not seek a fourth full term,[47] Abbott announced his candidacy for governor of Texas in the 2014 election.[48] In the first six months of 2011, he raised more money for his campaign than any other previous Texas politician, reaching $1.6 million. The next-highest fundraiser among state officeholders was Texas comptroller Susan Combs, with $611,700.[49]

Abbott won the Republican primary on March 4, 2014, with 91.5% of the vote. He faced State Senator Wendy Davis in the general election.[50]

Abbott promised to "tie outcomes to funding" for pre-K programs if elected,[51] but said he would not require government standardized testing for 4-year-olds, as Davis accused him of suggesting.[52] When defending his education plan, Abbott cited Charles Murray: "Family background has the most decisive effect on student achievement, contributing to a large performance gap between children from economically disadvantaged families and those from middle class homes."[53] A spokesman for Abbott's campaign pointed out that the biggest difference in spending was that Davis had proposed universal pre-K education while Abbott wanted to limit state funding to programs that meet certain standards.[53] Davis's plan could reach $750 million in cost and Abbott said that her plan was a "budget buster", whereas his education plan would cost no more than $118 million.[53] Overall, Abbott said the reforms he envisioned would "level the playing field for all students [and] target schools which don't have access to the best resources." He called for greater access to technology in the classroom and mathematics instruction for kindergarten pupils.[54]

Abbott received $1.4 million in campaign contributions from recipients of the Texas Enterprise Fund, some of whose members submitted the proper paperwork for grants.[55] Elliot Nagin of the Union of Concerned Scientists observed that Abbott was the recipient of large support from the fossil fuels industries, such as NuStar Energy, Koch Industries, Valero Energy, ExxonMobil, Chevron, and ConocoPhillips.[56] Abbott was endorsed by the Fort Worth Star-Telegram,[57] the Dallas Morning News,[58] the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal[59] and the Tyler Morning Telegraph.[60] He and Dan Patrick, the Republican nominee for lieutenant governor, were endorsed by the NRA Political Victory Fund and given an "A" rating.[61][62]

Abbott defeated Davis by over 20 percentage points in the November general election.[63][64][65][66]

2018 election

- >90%

- 80–90%

- 70–80%

- 60–70%

- 50–60%

- 40–50%

- 70–80%

- 60–70%

- 50–60%

- 40–50%

In January 2017, Abbott was reportedly raising funds for a 2018 reelection bid as governor; as of December 2016[update], he had $34.4 million on hand for his campaign, of which he had raised $9 million during the second half of 2016.[67][68] Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick had been mentioned as a potential challenger, but confirmed that he would run for reelection as lieutenant governor.[68] During the weekend of January 21, 2017, Abbott said that he intended to run for reelection.[69] He confirmed this on March 28, 2017.[70]

Abbott formally announced his reelection campaign on July 14, 2017.[71][72] This came four days before the start of a special legislative session that could split the Republican Party into factions favoring Abbott and Patrick on one hand and House speaker Joe Straus on the other. Straus represented the Moderate Republican faction, which opposes much of the social conservative agenda Abbott and Patrick pursued.

In the November 6 general election, Abbott defeated Democratic nominee Lupe Valdez with about 56% of the vote,[73][74][75][76] having outraised her 18 to 1.[77] He received 42% of the Hispanic and 16% of the African American vote.[78]

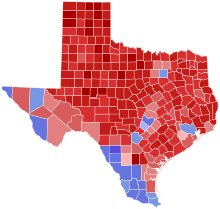

2022 election

- >90%

- 80–90%

- 70–80%

- 60–70%

- 50–60%

- 40–50%

- 70–80%

- 60–70%

- 50–60%

Abbott ran for a third term and faced challengers from within his own party,[79][80] including former Texas Republican Party chair Allen West and Don Huffines.[81][82] On March 1, he won the primary with over 66% of the vote. He was challenged by the Democratic nominee, former U.S. Representative Beto O'Rourke.[83] Abbott began with a large campaign funding advantage over his opponents, but was outraised by O'Rourke, who raised $81.6 million to Abbott's $78.5 million.[84][85]

Abbott defeated O'Rourke, 54% to 43%, becoming the fifth Texas governor to serve three terms, after Allan Shivers, Price Daniel, John Connally and Rick Perry.[86] He won 68% of Anglos, 18% of African Americans, and 42% of Latinos.[87]

2026 election

According to the Austin American Statesman, advisers close to Abbott have said he has not ruled out running for a fourth term in 2026, which would make him the longest-serving governor in state history with 16 years of service by January 21, 2031, surpassing former governor Rick Perry's 14 years.[88]

On March 1, 2024, Abbott announced his candidacy for reelection to a fourth term.[89]

Tenure as governor (2015–present)

Abbott was sworn in as governor of Texas on January 20, 2015, succeeding Rick Perry.[90][91] He is the first governor of Texas and the third elected governor of a U.S. state to use a wheelchair, after Franklin D. Roosevelt of New York (1929–1932) and George Wallace of Alabama (1963–1967, 1971–1979; 1983–1987).[92][93][94]

Abbott held his first meeting as governor with a foreign prime minister when he met with the Irish Taoiseach Enda Kenny on March 15, 2015, to discuss trade and economic relations.[95]

During the 2015 legislative session, initiated by officials at the Texas Health and Human Services Commission, the Texas legislature placed a rider to cut $150 million from its budget by ending payments and coverage for various developmental therapies for children on Medicaid. A lawsuit was filed against the state on behalf of affected families and therapy providers, claiming the cut could cause irreparable damage to the affected children's development.[96] The litigation obtained a temporary injunction order on September 25, 2015, barring THHSC from implementing therapy rate cuts.[97]

During Donald Trump's presidency, Abbott ardently supported Trump.[98] The Trump administration appointed several former Abbott appointees to federal courts, which some media outlets attributed to Abbott's influence on the administration.[99] In 2021, Trump endorsed Abbott for reelection, choosing him over several Republican primary rivals who also positioned themselves as pro-Trump.[100]

Abbott's book Broken But Unbowed (2016) recounted Abbott's personal story and views on politics.[101]

In October 2016, explosive packages were mailed to Abbott, President Obama, and the Commissioner of the Social Security Administration. Abbott's package did not explode when he opened it because "he did not open [the package] as intended".[102]

On June 6, 2017, Abbott called for a special legislative session in order to pass several of his legislative priorities,[103][104] an agenda supported by Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick.[105] Abbott vetoed 50 bills in the regular 2017 session, the most in a session since 2007.[106][107]

Abbott appointed multiple judges to various judgeships, including several GOP-affiliated judges who had recently lost local judicial elections.[108]

After the regular 2021 session, The New York Times called Abbott and Patrick "the driving force behind one of the hardest right turns in recent state history".[109] Other sources said Abbott and other state officials advanced strongly conservative policies.[110][111][112] By his 2022 reelection campaign, Abbott more prominently emphasized "culture war" issues.[113] He had been compared to Florida Governor Ron DeSantis in promoting conservative policies.[114][115]

According to a report by The Texas Tribune and ProPublica, Abbott centralized power under the governor's office during his tenure.[116]

Abortion

In November 2016, the State of Texas, at Abbott's request, approved new rules that require facilities that perform abortions either to bury or cremate the aborted, rather than dispose of the remains in a sanitary landfill.[117][118] The rules were intended to go into effect on December 19,[117] but on December 15 a federal judge blocked them from going into effect for at least one month after the Center for Reproductive Rights and other advocacy groups filed a lawsuit.[119] On January 27, 2017, a federal judge ruled against the law, but the State of Texas vowed to appeal the ruling.[120]

On June 6, 2017, Abbott signed a bill into law banning dismemberment and partial-birth abortions and requiring either burial or cremation of the aborted.[121][122][123] That law was also blocked by a federal judge; the state said it would appeal.[124][125]

On May 18, 2021, Abbott signed the Texas Heartbeat Act, a six-week abortion ban, into law.[126][127] In September 2021, he signed into law a bill preventing women from mail-ordering abortion medication seven weeks into pregnancy.[128]

Convention of States proposal

In 2016, Abbott spoke to the Texas Public Policy Foundation, calling for a Convention of States to amend the U.S. Constitution. In his speech, he proposed the Texas Plan, a series of nine new amendments to "unravel the federal government's decades-long power grab "to impose fiscal restraints on the federal government and limit the federal government's power and jurisdiction." The plan would limit the power of the federal government and expand states' rights, allowing the states to nullify federal law under some circumstances.[129][130]

On January 8, 2016, Abbott called for a national constitutional convention to address what he saw as abuses by justices of the United States Supreme Court in "abandoning the Constitution."[131] Speaking to the Texas Public Policy Foundation, Abbott said, "We the people have to take the lead to restore the rule of law in the United States."[132] Abbott elaborated on his proposal in a public seminar at the Hoover Institute on May 17, 2016.[133]

Criminal justice

In the wake of the George Floyd protests, Abbott called on candidates in the 2020 elections to "back the blue."[134] In response to actions by some Texas cities to redirect funding from police to social services and emergency response, he threatened that the state of Texas would seize control of the local police departments.[135][134] In 2021, Abbott spearheaded legislative efforts to financially penalize cities in Texas that reduce spending on police.[136]

In 2021, Abbott vetoed a bipartisan criminal justice bill that would have made people convicted of certain crimes before the age of 18 eligible for early parole and created panels to consider inmates' age and mental status at the time of their crimes when evaluating parole eligibility.[137] He also vetoed legislation to prohibit police from using statements made under hypnosis in criminal court.[137] He also vetoed an animal protection bill that would have made it illegal to chain up dogs without giving them access to drinkable water and shade or shelter.[137]

In May 2024, Abbott granted a full pardon to former Army Sergeant Daniel Perry after the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles unanimously recommended a pardon.[138] Perry was sentenced to 25 years in prison in 2023 for fatally shooting Air Force veteran Garrett Foster during a Black Lives Matter protest. In 2023, Abbott said he would work swiftly for a pardon after a jury convicted Perry of murder.[139]

Firearms

In 2015, Abbott signed the campus carry (SB 11) and the open carry (HB 910) bills into law.[140] The campus carry law came into effect later that year, allowing licensed carry of a concealed handgun on public college campuses, with private colleges able to opt out.[140][141] The open carry bill went into effect in 2016, allowing licensed open carry of a handgun in public areas and private businesses unless they display a "30.07" sign, referring to state penal code 30.07, which states that a handgun may not be carried openly even by a licensed gun carrier. To do so is considered trespassing.[140][141][142] Texas is the 45th state to have open carry.[143] In 2017, Abbott signed into law a bill lowering handgun carry license fees.[144] In 2021, he signed into law a bill that allowed Texans to carry guns without a license.[145]

In an interview with Fox News following the November 5, 2017, Sutherland Springs church shooting, Abbott urged historical reflection and the consideration that evil had been present in earlier "horrific events" during the Nazi era, the Middle Ages and biblical times.[146] The Anti-Defamation League called his comparison of the shooting "to the victims of the Holocaust" "deeply offensive" and "insensitive".[147][148]

After the 2018 Santa Fe High School shooting, Abbott said that he would consult across Texas in an attempt to prevent gun violence in schools.[149] A series of round-table discussions followed at the state capitol.[150] In a speech at an NRA convention in Dallas almost two weeks after the shooting, Abbott said, "The problem is not guns, it's hearts without God".[151] In June 2019, he signed a bill allowing for more armed teachers, with school districts unrestricted as to the number they allow.[152] The creation of "threat assessment teams", included in the bill, is intended to identify potentially violent students.[153] Although the state legislature passed measures for students services to deal with related mental health issues, proposals to adopt a red flag law failed. Abbott said such a law was "not necessary in the state of Texas."[152]

In August 2019, a gunman who had written a racist manifesto killed 22 people in a mass shooting at a Wal-Mart in El Paso, saying he had targeted "Mexicans".[154] After the shooting, Abbott convened a domestic terrorism task force to look into domestic extremism, but reiterated his opposition to a red-flag law and rejected calls to convene a special session of the state legislature to address gun violence.[154]

In June 2021, Abbott signed into law a permitless carry bill allowing Texans to carry handguns without a license or training beginning in September 2021.[155]

On May 24, 2022, Abbott said that an 18-year-old carrying a handgun and possibly a rifle (later identified as a Daniel Defense DDM4, an AR-15 style rifle)[156] killed 19 students and 2 teachers at the Robb Elementary School in Uvalde.[157] On May 25, Abbott held a news conference to give further information on the shooting. Abbott said that mental health in the community was the root cause of the event. Beto O'Rourke, who was running for the Democratic nomination for governor in 2022, approached the stage and said, "The time to stop the next shooting is right now and you are doing nothing." Abbott responded that it was a time for "healing and hope" for the victim's families, not "our agendas."[158] Rather than attend the annual NRA meeting on May 27, Abbott published a YouTube message. He said that gun laws have not been effective, noting that the shooter broke two gun laws the day he committed the multiple murders. It is a felony to possess a gun on school property, and "what he did on campus is capital murder. That's a crime that would have subjected him to the death penalty in Texas".[159]

Jade Helm 15

In April 2015, Abbott asked the State Guard to monitor the military training exercise Jade Helm 15, amid Internet-fueled suspicions that the war simulation was really a hostile military takeover.[160][161][162][163] In 2018, former director of the CIA and NSA Michael Hayden said that Russian intelligence organizations had propagated the conspiracy theory and that Abbott's response convinced them of the power such a misinformation campaign could have in the United States.[164]

Religion

In 2015, Abbott signed the Pastor Protection Act, which allows members of the clergy to refuse to marry same-sex couples if they feel doing so violates their beliefs.[165]

In 2017, Abbott signed into law Senate Bill 24, preventing state or local governments from subpoenaing pastors' sermons.[166][167] The bill was inspired by an anti-discrimination ordinance in Houston, where five pastors' sermons were subpoenaed.[166]

Also in 2017, Abbott signed House Bill 3859, which allows faith-based groups working with the Texas child welfare system to deny services "under circumstances that conflict with the provider's sincerely held religious beliefs." Democrats and civil rights advocates said the adoption bill could allow such groups to discriminate against those who practice a different religion or who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender, and LGBT rights groups said they would challenge the bill in court.[168][169] In response, California added Texas to a list of states to which it banned official government travel.[170]

Immigration and border security

In June 2015, Abbott signed a bill bolstering Texas's border security operations, including hiring additional state police, expanding the use of technology, and creating intelligence operations units.[171] In November 2015, he announced that Texas would refuse Syrian refugees following the Paris terrorist attack earlier that month. In December 2015, Abbott ordered the Texas Health and Human Services Commission to sue the federal government and the International Rescue Committee to block refugee settlement, but a federal district court struck the lawsuit down.[172]

In February 2017, Abbott blocked funding to Travis County, Texas, due to its recently implemented sanctuary city policy.[173][174] In May 2017, he signed into law Texas Senate Bill 4, targeting sanctuary cities by charging county or city officials who refuse to work with federal officials and allowing police officers to check the immigration status of those they detain.[175][176]

In January 2020, Abbott made Texas the first state to decline refugee resettlement under a new rule implemented by the Trump administration.[177] In a joint statement, all sixteen Catholic bishops of Texas condemned the move.[178]

In 2021, Abbott said that illegal immigrants were invading homes.[179] In March 2021, he tweeted, "The Biden Administration is recklessly releasing hundreds of illegal immigrants who have COVID into Texas communities." PolitiFact rated Abbott's claim "Mostly False", since those being released were asylum seekers with a legal right to remain in the U.S., and the number was well below "hundreds", only 108, at the time of the tweet.[180]

In June 2021, Abbott ordered Texas child-care regulators to take the licenses of child-care facilities that housed unaccompanied migrant minors. He said that housing unaccompanied minors in child-care facilities had a negative impact on facilities housing Texan children in foster care.[181] Later that month, he announced plans to build a border wall with Mexico, saying that the state would provide $250 million and that direct donations from the public would be solicited.[182][183]

In July 2021, Abbott advised state law enforcement officers to begin arresting illegal migrants for trespassing.[184][185] On July 27, 2021, he ordered the National Guard to begin helping arrest migrants,[186][187] and the next day he signed an order to restrict the ground transportation of migrants.[188][189][190] Migrants arrested under Abbott's policy were imprisoned for weeks without legal help or formal charges.[191] By December 2023, nearly 10,000 migrants had been arrested on trespassing charges.[192][193]

In September 2021, Abbott signed legislation spending nearly $2 billion on Texas's border security operations, including $750 million for border wall construction.[194] This was a significant increase, and supplemented $1 billion already appropriated for border security in the two-year state budget.[194][195] In December 2021, Abbott announced that Texas would continue the U.S. Border Wall started by Donald Trump.[196] The wall has the same design as Trump's and is under construction.

In April 2022, Abbott announced in a press conference a plan to direct the Texas Division of Emergency Management to bus illegal immigrants with 900 charter buses from Texas to Washington D.C, citing the potential surge of immigrants who would cross the border after Title 42 provisions regarding communicable disease were set to be rolled back by President Biden the next month.[197] Any mayor, county judge, or city could request buses for immigrants who had been released from federal custody.[198] After initial criticism, Abbott clarified that the trip would be voluntary for immigrants.[199] Later in April the first bus, carrying 24 immigrants, arrived in Washington D.C after a 30-hour trip.[200] A second bus arrived the next day.[201] Abbott came under fire for both buses, with one American Enterprise Institute scholar suggesting he be federally prosecuted for human trafficking. Senator Ted Cruz supported Abbott's actions and advocated that more immigrants be bused into other predominantly Democratic areas.[202] In a press conference, White House press secretary Jen Psaki said it was "nice" that Texas was "helping them get to their final destination as they await the outcome of their immigration proceedings".[203] Washington D.C. mayor Muriel Bowser responded to the influx of migrants from Texas by requesting National Guard support for what she termed a "migrant crisis".[204]

On September 15, 2022, Abbott sent two buses with 101 mostly Venezuelan migrants detained after crossing the U.S. border with Mexico to the residence of Vice President Kamala Harris, at the Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C.[205] On September 17, Abbott sent another bus with 50 migrants to Harris's residence.[206]

In June 2023, Abbott deployed floating barriers in the Rio Grande in an effort to deter illegal border crossings.[207] The U.S. Justice Department sued Abbott and the state of Texas after Abbott refused to remove the barriers.[208]

In December 2023, Abbott signed three border-security-related bills into law, including a bill making illegal immigration a state crime.[209][210][211]

Border inspections

In early April 2022, Abbott announced that Texas would increase inspections of commercial trucks entering from Mexico with the goal of seizing illegal drugs and illegal migrants.[212] Shortly thereafter, the inspections caused a multi-mile backup of commercial vehicles carrying produce, auto parts, household goods and many other items. A spokesman for the Fresh Produce Association of the Americas said that up to 80% of perishable fruits and vegetables had been unable to cross and in some cases were in danger of spoiling. The president of the Texas Trucking Association said the delays were affecting every kind of trucking and being felt across the country.[213] Mexican truckers blockaded several bridges in protest.[214] Under heavy pressure from Texas business owners, who strongly criticized the "secondary inspections", Abbott canceled the policy on April 15. He said the reversal was because the governors of adjacent Mexican states had agreed to exercise stronger vigilance against human trafficking, drugs, and guns.[215]

Abbott's truck inspections ultimately cost Texas an estimated $4.2 billion and led to no apprehensions of drugs or illegal migrants.[216]

Environment

As of 2018[update], Abbott rejects the scientific consensus on climate change. He has said that the climate is changing, but does not accept the consensus that human activity is the main reason.[217][218]

In early 2014, Abbott participated in sessions held at the headquarters of the United States Chamber of Commerce to devise a legal strategy to dismantle climate change regulations.[219] In 2016, he supported Scott Pruitt's appointment as head of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), saying, "He and I teamed up on many lawsuits against the EPA."[220] As Texas attorney general, Abbott often sued the federal government over environmental regulations.[221]

After Joe Biden was elected president, Abbott vowed to pursue an aggressive legal strategy against the Biden administration's environmental regulations.[222]

Voting rights

Abbott pressed for a purge of nearly 100,000 registered voters from Texas voter rolls. Texas officials initially claimed that the voters to be purged were not American citizens. The purge was canceled in April 2018 after voting rights groups challenged the purge, and officials at the Office of the Texas Secretary of State admitted that tens of thousands of legal voters (naturalized citizens) were wrongly flagged for removal. Abbott claimed that he played no role in the voter purge, but emails released in June 2019 showed that he was the driving force behind the effort.[223]

In September 2020, Abbott issued a proclamation that each Texas county could have only one location where voters could drop off early voting ballots. He justified the decision by claiming it would prevent "illegal voting" but cited no examples of voter fraud. Election security experts say voter fraud is extremely rare.[224][225] Also in September 2020, Abbott extended the early voting period for that year's general election due to COVID-19; the Republican Party of Texas opposed his decision.[226]

Abbott made "election integrity" a legislative priority after President Trump's failed attempts to overturn the election results of 2020 United States presidential election by using baseless claims that the results were fraudulent.[227] Voting rights advocates and civil rights groups denounced the resulting legislation, saying it disproportionately affected voters of color and people with disabilities.[228]

In July 2021, Democratic lawmakers in the Texas legislature fled the state on a chartered flight to Washington, D.C., in an effort to block the passage of a bill that would reform the state election procedures.[229] Abbott threatened to have the lawmakers arrested upon their return to Texas.[230] In August, the Supreme Court of Texas made a ruling allowing for the arrest of the absent lawmakers, so they could be brought to the state capitol.[231]

In October 2021, Abbott appointed John Scott as Texas Secretary of State, putting him in a position to oversee Texas elections. Scott aided Trump in his failed efforts to throw out election results in the 2020 presidential election.[232][233]

LGBT rights

In 2014, Abbott defended Texas's ban on same-sex marriage, which a federal court ruled unconstitutional.[234] As attorney general of Texas, he argued that the prohibition on same-sex marriage incentivized that children would be born "in the context of stable, lasting relationships."[234]

Abbott condemned Obergefell v. Hodges, the Supreme Court ruling that same-sex marriage bans are unconstitutional.[235] He said, "the Supreme Court has abandoned its role as an impartial judicial arbiter."[235] Shortly thereafter, Abbott filed a lawsuit to stop same-sex spouses of city employees from being covered by benefit policies.[236]

In a letter dated May 27, 2017, the CEOs of 14 large technology companies, including Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon, urged Abbott not to pass what came to be known as the "bathroom bill":[237] legislation requiring people to use the bathroom of the sex listed on their birth certificates, not the one of their choice. The bill was revived by Abbott and supported by Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick.[238] In March 2018, Byron Cook, the chairman of the House State Affairs committee who blocked the bill, claimed that Abbott privately opposed the bill.[239] The bill was never signed; Abbott later said, "it's not on my agenda" in a debate with Lupe Valdez, the Democratic nominee for governor in 2018.[240]

In 2017, Abbott signed legislation to allow taxpayer-funded adoption agencies to refuse same-sex families from adopting children for religious reasons.[241]

In 2021, a Republican primary challenger criticized Abbott because Texas's child welfare agency included content regarding LGBTQ youths. Shortly thereafter, the agency, whose members Abbott appoints, removed the webpage that included a suicide prevention hotline and other resources for LGBT youths.[242]

In 2022, Abbott instructed Texas state agencies to treat gender-affirming medical treatments (such as puberty blockers or hormone treatments) for transgender youths as child abuse.[243][244][245]

Homelessness

In June 2019, the city of Austin introduced an ordinance that repealed a 25-year-old ban on homeless people camping, lying, or sleeping in public.[246] In October 2019, Abbott sent a widely publicized letter to Austin Mayor Steve Adler criticizing the camping ban repeal and threatened to deploy state resources to combat homelessness.[247]

In November 2019, Abbott directed the State of Texas to open a temporary homeless encampment on a former vehicle storage yard owned by the Texas Department of Transportation, which camp residents dubbed "Abbottville".[248]

Marijuana

In 2019, when numerous local prosecutors announced that they would stop prosecuting low-level marijuana offenses, Abbott instructed them to continue enforcing marijuana laws.[249][250][251] The prosecutors cited recently passed legislation that legalized hemp. As hemp contains the same chemical as marijuana, THC, tests at law enforcement's disposal cannot distinguish between marijuana usage and hemp usage.[250] Abbott has said that legal hemp products come with a "hemp certificate".[250]

In 2022, a poll of Texas voters found that 55% of Texans either support or strongly support legalizing cannabis.[252]

COVID-19 pandemic

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Abbott issued a stay-at-home order from April 2 to May 1, 2020.[253][254] This was one of the shortest stay-at-home orders implemented by any governor.[254] After Texas started to reopen, COVID-19 surged, leading Abbott to pause the reopening.[254] On June 24, Texas broke its record of new COVID-19 cases in a day.[254] Critics described Abbott's pause as a half-measure and argued that he should reverse the reopening in full to limit the virus's spread.[254]

According to The New York Times, Abbott's response to the pandemic has been contradictory, as he has said that Texans should stay at home while also saying that Texas is open for business.[254] He also said that Texans should wear face masks but refused to issue a statewide mandate.[254] Abbott's response to the pandemic has been criticized on both sides of the political spectrum.[254] In July 2020, he directed counties with more than 20 COVID-19 cases to wear masks in public places; he had previously prohibited local governments from implementing required face masks.[255]

In December 2020, Abbott directed Texas restaurants to ignore local curfews that had been imposed to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Localities had implemented restrictions on indoor dining and drinking late at night on New Years weekend amid a surge in COVID-19 cases.[256][257]

On March 2, 2021, Abbott lifted all COVID-19 restrictions in Texas, which included ending a mask mandate and allowing businesses to reopen "100 percent."[258]

In April 2021, Abbott signed an executive order banning state agencies and corporations that take public funding from requiring proof of vaccination against COVID-19.[259] In June 2021, he signed a bill that would punish businesses that require customers to have proof of COVID-19 vaccination for services.[260]

On May 18, 2021, Abbott issued an executive order banning mask mandates in public schools and governmental entities, with up to a $1,000 fine for non-compliers.[261]

On August 17, 2021, Abbott's office announced that he had tested positive for COVID-19. According to his office, Abbott was "in good health and experiencing no symptoms".[262] He received Regeneron's monoclonal antibody treatment.[263]

Abbott emphasized personal responsibility over government restrictions, and resolutely opposed government mandates in August 2021.[264] On July 29, 2021, during an again worsening pandemic,[265][266] he issued a superseding executive order (GA-38) that reinstated earlier orders and imposed additional prohibitions on local governmental officials, state agencies, public universities,[267] and businesses doing business with the state, to prohibit them from adopting measures such as requiring face masks or proof of vaccination status as a condition of service. The order also provides for a $1,000 fine for local officials who adopt inconsistent policies.[268][269][270] President Biden criticized Abbott for these measures.[271] The ban on mask mandates led to a score of legal challenges between Abbott and local governments, including school districts.[272] In justifying the ban on local government mandates in August 2021, an Abbott spokesperson said, "Private businesses don't need government running their business."[273] In October 2021, Abbott issued an executive order that banned any entity, including a private business, from implementing a vaccine requirement for its employees.[274]

February 2021 North American ice storm

During the February 13–17, 2021 North American winter storm, power-plant failures across Texas left four million households in Texas without power.[275] Abbott called for investigation and reform of the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), the electric grid operator for most of Texas.[276]

On February 16, on Hannity, Abbott said, "This shows how the Green New Deal would be a deadly deal for the United States of America ... Our wind and our solar got shut down, and they were collectively more than 10 percent of our power grid, and that thrust Texas into a situation where it was lacking power on a statewide basis... It just shows that fossil fuel is necessary." The Texas energy department[clarification needed] clarified that a failure to winterize the state's power grid caused most of the losses.[277][276] Most power plants in Texas are gas-fired, with wind generators providing about 10% during the winter.[276]

By February 18, Abbott had ordered Texas natural gas to sell exclusively to power generators in Texas, which had an immediate and direct impact on Mexico, where gas-fired plants generate two-thirds of all energy.[278] In June 2021, Abbott signed a bill requiring power companies to be more prepared for extreme weather events.[279]

College diversity, equity, and inclusion

In the summer of 2023, Abbott signed into law Senate Bill 17, which prohibits Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) offices at Texas's public colleges and universities.

The bill, passed largely along party lines, garnered both support and criticism, with proponents arguing it would save taxpayer funds and promote a merit-based approach to education and critics expressing concern about discrimination and hindrance to diversity efforts.[280]

As a result of Senate Bill 17 and similar legislation, universities have been compelled to reevaluate their diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, often leading to significant restructuring and reallocation of resources.[281] At the University of Texas-Austin, Senate Bill 17's implementation led to the layoff of approximately 60 employees and the closure of the Division of Campus and Community Engagement, which was formerly the Division of Diversity and Community Engagement.[282]

Personal life

Abbott, a Catholic, is married to Cecilia Phalen Abbott, the granddaughter of Mexican immigrants.[283][284][285] They were married in San Antonio in 1981.[3] His election as governor of Texas made her the first Latina to be First Lady of Texas since Texas joined the union.[284][286] They have one adopted daughter, Audrey.[11][283][284] Cecilia is a former schoolteacher and principal.[8]

Wheelchair use

On July 14, 1984, at age 26, Abbott was paralyzed below the waist when an oak tree fell on him while he was jogging after a storm.[8][287] Two steel rods were implanted in his spine, and he underwent extensive rehabilitation at TIRR Memorial Hermann in Houston and has used a wheelchair ever since.[288][289] He sued the homeowner and a tree service company, resulting in an insurance settlement that provided him with lump sum payments every three years until 2022 along with monthly payments for life, both of which were adjusted for inflation.[290] As of August 2013, the monthly payment was US$14,000 and the three-year lump sum payment was US$400,000, all tax-free.[update] Abbott has said he relied on the money to pay for nearly three decades of medical expenses and other costs.[290]

Electoral history

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Greg Abbott | 4,437,099 | 54.8 | ||

| Democratic | Beto O'Rourke | 3,553,656 | 43.9 | ||

| Libertarian | Mark Tippets | 44,805 | 1.0 | ||

| Green | Delilah Barrios | 28,584 | 0.3 | ||

| Republican hold | |||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Greg Abbott | 4,656,196 | 55.8 | ||

| Democratic | Lupe Valdez | 3,546,615 | 42.5 | ||

| Libertarian | Mark Tippets | 140,632 | 1.7 | ||

| Republican hold | |||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Greg Abbott | 2,790,227 | 59.3 | ||

| Democratic | Wendy Davis | 1,832,254 | 38.9 | ||

| Libertarian | Kathie Glass | 66,413 | 1.1 | ||

| Green | Brandon Parmer | 18,494 | 0.4 | ||

| Independent | Sarah M. Pavitt | 1,168 | <0.1 | ||

| Republican hold | |||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Greg Abbott | 3,151,064 | 64.1 | ||

| Democratic | Barbara Ann Radnofsky | 1,655,859 | 33.7 | ||

| Libertarian | Jon Roland | 112,118 | 2.3 | ||

| Republican hold | |||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Greg Abbott | 2,556,063 | 59.5 | ||

| Democratic | David Van Os | 1,599,069 | 37.2 | ||

| Libertarian | Jon Roland | 139,668 | 3.3 | ||

| Republican hold | |||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Greg Abbott | 2,542,184 | 56.7 | ||

| Democratic | Kirk Watson | 1,841,359 | 41.1 | ||

| Libertarian | Jon Roland | 56,880 | 1.3 | ||

| Green | David Keith Cobb | 41,560 | 0.9 | ||

| Republican hold | |||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Greg Abbott | 2,104,828 | 60.1 | ||

| Democratic | David Van Os | 1,396,924 | 39.9 | ||

| Republican hold | |||||

References

- ^ "TJB | SC | About the Court | Court History | Justices Since 1945 | Justices, Place 5". txcourts.gov. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ "Biography of Greg Abbott". Texapedia. Retrieved April 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Sweany, Brian D. (October 2013). "The Overcomer". Texas Monthly. Austin, Texas. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ "Person Details for Gregory Wayne Abbott, "Texas, Birth Index, 1903–1997"". FamilySearch.org. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ^ vote-smart.org. Archived October 23, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Wilson, Reid (October 30, 2014). "The likely next governor of Texas is full of Lone Star swagger. Don't be surprised if he runs for president". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ "Texas Governor Greg Abbott". Retrieved April 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "oag.state.tx.us". oag.state.tx.us. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ^ "Race Summary Report - 1996 General Election". Texas Secretary of State. November 5, 1996. Archived from the original on June 9, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ "Race Summary Report - 1998 General Election". Texas Secretary of State. November 3, 1998. Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ a b Mildenberg, David and Laurel Brubaker Calkins. Grit Drives Abbott to Follow Perry as Texas Governor, Bloomberg Businessweek, September 19, 2013.[dead link]

- ^ "Attorney General Greg Abbott's Biography". Project VoteSmart.org. November 13, 1957. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ^ Goudeau, Ashley (April 30, 2020). "State Sen. Kirk Watson headed to University of Houston". KVUE. Archived from the original on May 6, 2020. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- ^ "Race Summary Report - 2002 General Election". Texas Secretary of State. November 5, 2002. Archived from the original on February 27, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ Root, Jay (August 4, 2013). "Abbott Faces Questions on Settlement and His Advocacy of Tort Laws". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- ^ "Greg Abbott shares views with local Republicans". SAST. February 19, 2013. Archived from the original on April 24, 2013. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ Satija, Neena; Carbonell, Lindsay; McCrimmon, Ryan (January 17, 2017). "Texas vs. the Feds — A Look at the Lawsuits". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ^ Frosch, Dan; Gershman, Jacob (June 24, 2016). "Abbott's Strategy in Texas: 44 Lawsuits, One Opponent: Obama Administration; Former Attorney General, Now Governor, has Led a Red-State Revolt Against the White House". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ "Trump's EPA pick sued Obama's agency early and often with anti-climate change ally Greg Abbott". dallasnews.com. December 7, 2016. Retrieved February 18, 2018.

- ^ "Why the blue states' climate alliance may not work". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved February 18, 2018.

- ^ Root, Jay (July 1, 2014). "Abbott: Ask Chemical Plants What's Inside". The Texas Tribune. texastribune.org. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ Slater, Wayne (July 3, 2014). "Koch Industries says gifts, Abbott's chemical ruling not linked". The Dallas Morning News. The Dallas Morning News Inc. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ Solomon, Dan (March 27, 2014). "Greg Abbott Enters Fray in Lawsuits Involving "Sociopath" Doctor". Texas Monthly. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- ^ Swanson, Doug J. (March 2014). "Abbott sides with Baylor hospital in neurosurgeon lawsuit". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- ^ a b Robert T. Garrett, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott says tighter restrictions on mail-in ballot procedures will deter voter fraud, Dallas Morning News (February 2, 2020).

- ^ a b c d e f "Texas Sues Sony BMG Alleging Violation of Texas Spyware Statute". Tech Law Journal. November 20, 2005. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Texas Attorney General's Office (November 21, 2014). "Attorney General Abbott Brings First Enforcement Action In Nation Against Sony BMG For Spyware Violations". State of Texas. Austin, Texas. Archived from the original on January 1, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ "News | Office of the Attorney General". Archived from the original on November 20, 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2013., oag.state.tx.us.

- ^ a b c "AG throws more allegations at Sony BMG". The Business Journals. December 21, 2005. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ^ "Attorney General ups the ante in lawsuit against Sony BMG". The Business Journals. December 22, 2005. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ^ Robert McMillan, Sony pays $1.5M to settle Texas, CA rootkit suits, IDG News Service (December 19, 2005).

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda (February 28, 2005). "The Ten Commandments Reach the Supreme Court". The New York Times. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

- ^ Mears, Bill. "Supreme Court weighs Ten Commandments cases". CNN. Archived from the original on March 4, 2005.

- ^ Curry, Tom (August 27, 2005). "Breyer Cast Decisive Vote on Religious Displays". NBC News. Archived from the original on January 24, 2015. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- ^ Jim Forsyth (January 17, 2013). "Y'all come to Texas, state official tells New York gun owners". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 12, 2019.

- ^ Fernandez, Manny (January 20, 2013). "Texas Attorney General to New Yorkers: Come on Down, With Guns". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- ^ Poppe, Ryan (February 26, 2014). "Supreme Court Won't Hear NRA's Case For Lowering Conceal-Carry Age Limit". tpr.org. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Root, Jay (August 4, 2013). "Abbott Faces Questions on Settlement and His Advocacy of Tort Laws". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "A Closer Look at Greg Abbott's Anti-Gay Marriage Arguments". The Texas Observer. July 30, 2014. Retrieved June 8, 2019.

- ^ "Texas attorney general: 'ban on same-sex marriage promotes childbirth'". The Guardian. Associated Press. July 29, 2014. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved June 8, 2019.

- ^ Lindell, Chuck. "Greg Abbott presses Texas Supreme Court to limit gay-marriage ruling". Austin American-Statesman. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- ^ Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584 (2015).

- ^ "Race Summary Report - 2006 General Election". Race Summary Report - 2006 General Election. November 7, 2007. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ "Race Summary Report - 2010 General Election". Texas Secretary of State. November 2, 2010. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ Root, Jay (November 4, 2014). "Greg Abbott Crushes Wendy Davis in GOP Sweep". The Texas Tribune. Austin, Texas. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ^ Ackerman, Todd; Berger, Eric (July 29, 2013). "Abbott's role at cancer agency under fire". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ "Rick Perry Won't Run for Re-election". The Texas Tribune. July 8, 2013. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ^ "Texas AG Abbott kicks off gubernatorial run". Archived from the original on July 14, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ "Greg Abbott and the Quiet Spot at the Top". The Texas Tribune. August 12, 2011. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ^ "Republican primary election returns, March 4, 2014". team1.sos.state.tx.us. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ^ Alexander, Kate (March 31, 2014). "Greg Abbott promotes improving quality of pre-K over expanding access, full-day classes". statesman.com. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ^ Smith, Morgan; Ura, Alexa (April 8, 2014). "Abbott Campaign: Pre-K Plan Does Not Mean More Tests". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c Hoppe, Christy (April 1, 2014). "Greg Abbott's education plan cites controversial thinker on race, gender". The Dallas Morning News. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- ^ "Texas Gubernatorial Candidate: Greg Abbott speaks about state issues, Laredo Morning Times, May 16, 2014, pp. 1, 14A

- ^ Slater, Wayne (September 28, 2014). "Greg Abbott shielded problem-plagued business fund by withholding applications that didn't even exist". The Dallas Morning News. The Dallas Morning News Inc. Archived from the original on October 3, 2014. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ^ Negin, Elliott (June 9, 2016). "After the Deluge: Texas and France Split on Climate Science". huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved February 18, 2018.

- ^ "For governor, Abbott holds promise". Editorial Board. Fort Worth Star-Telegram. October 19, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ "Editorial: We recommend Greg Abbott for Texas governor". Dallas Morning News. Dallas, Texas. October 16, 2014.

- ^ "Our View: Attorney General Greg Abbott is the best gubernatorial candidate". Editorial Board. Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. Lubbock, Texas. October 18, 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ "Greg Abbott ready to be our governor". Editorial Board. Tyler Morning Telegraph. Tyler, Texas. October 18, 2014.

- ^ "NRA-PVF | Texas". NRA-PVF. Archived from the original on November 4, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Reynolds, John (September 18, 2014). "NRA Endorses Abbott, Patrick". The Texas Tribune. Archived from the original on May 19, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- ^ Root, Jay (November 4, 2014). "Abbott Crushes Davis in GOP Sweep". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ Hoppe, Christy (November 5, 2014). "Greg Abbott Tops Wendy Davis in Texas Governor's Race". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ Herskovitz, Jon (November 4, 2014). "Republican Greg Abbott Wins Texas Governor's Race". Reuters. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ Root, Jay (November 6, 2014). "Wendy Davis Lost Badly. Here's How it Happened". The Washington Post. The Texas Tribune. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ Svitek, Patrick (January 12, 2017). "Greg Abbott Builds Big War Chest Ahead of 2018". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- ^ a b Peggy Fikac, "Abbott adds $9 million to campaign war chest", San Antonio Express-News, January 13, 2017, p. A4

- ^ Whitely, Jason (January 22, 2017). "Abbott to Run for Re-Election, Explains Position on Bathroom Bill". WFAA. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- ^ Jeffers, Gromer Jr. (March 28, 2017). "Gov. Greg Abbott Remains Coy About 'Bathroom Bill,' Says He'll Run for Re-Election". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- ^ Root, Jay (July 14, 2017). "With No Opposition in Sight, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott Formally Launches 2018 Re-Election Bid". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- ^ Peggy Fikac, "Abbott to seek second term: Governor says in S.A. he's ready to fight liberals," San Antonio Express-News, July 15, 2017, pp 1, A2.

- ^ Zdun, Matt; Collier, Kiah (November 6, 2018). "Gov. Greg Abbott clinches second term as GOP wins closest statewide races in 20 years". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ Samuels, Brett (November 6, 2018). "Texas governor Greg Abbott wins reelection". The Hill. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ Garrett, Robert T. (November 6, 2018). "For Gov. Greg Abbott, a victory, though not the towering one he'd hoped for over Lupe Valdez". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ Weber, Paul J. (November 6, 2018). "No surprise here: Greg Abbott easily defeats Lupe Valdez, re-elected as Texas governor". Fort Worth Star-Telegram (from the Associated Press). Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ Sanchez, Carlos (November 6, 2018). "Greg Abbott Wins a Second Term as Governor". Texas Monthly. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- ^ Manuel, Obed (April 29, 2019). "More Texas Latinos voted in 2018, but so did everyone else, census data shows". Dallas Morning News. Dallas, Texas. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

'In spite of the Democrats increasing their election turnout, we were able to grow our turnout as well, and do so enough that for the 12th election in a row, every single statewide office was retained by Republicans,' James Dickey said. He added that Latino voters, 42 percent of whom voted for Abbott, will continue playing a key role for the Texas GOP.

- ^ Tilove, Jonathan (June 14, 2019). "Tilove: Abbott says Biden will fade and Trump will win Texas". Austin American-Statesman. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

He said he plans to run for a third term in 2022.

- ^ Svitek, Patrick (May 10, 2021). "Republican former state Sen. Don Huffines launches primary challenge to Gov. Greg Abbott". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ^ Svitek, Patrick (March 2, 2022). "Greg Abbott, Beto O'Rourke easily win gubernatorial primaries, setting up November race". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- ^ Svitek, Patrick (July 4, 2021). "Allen West announces he is running against Gov. Greg Abbott in Republican primary". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ^ Svitek, Partick (November 15, 2021). "Beto O'Rourke says he's running for Texas governor". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved January 6, 2022.

- ^ Svitek, Patrick (July 8, 2021). "Texas Gov. Greg Abbott has colossal $55 million war chest for 2022 reelection bid". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ^ Lau, Carla Astudillo, Caroline Covington and Eric (July 20, 2022). "Greg Abbott and Beto O'Rourke broke fundraising records in their race for Texas governor. Here's how much". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "2022 US Governor Election Results: Live Map". ABC News. November 9, 2022. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

- ^ "Fox News Voter Analysis". Fox News.

- ^ "Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick will seek fourth term as conservative priorities take shape in Senate".

- ^ Watkins, Matthew (March 1, 2024). "Donald Trump says Greg Abbott is "absolutely" on vice president short list". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ Fernandez, Manny (January 20, 2015). "Texas' New Governor Echoes the Plans of Perry". The New York Times. Retrieved January 24, 2015.

- ^ Whitely, Jason (January 20, 2015). "Abbott, Patrick Sworn in as new Texas Leaders" Archived January 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. WFAA.com. Retrieved January 24, 2015.

- ^ "Greg Abbott's election in Texas opens possibilities for disabled". USA Today. November 5, 2014. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ "Greg Abbott and the new politics of disability". Austin American-Statesman. September 24, 2016. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ Root, Jay (November 5, 2014). "Abbott Crushes Davis in GOP Sweep". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ "Abbott Discusses Trade With Irish Prime Minister". Texas Tribune. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ "Texas to Move Forward With Cuts to Children's Therapy". The Texas Tribune. August 26, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ^ "Citing 'irreparable injury' to kids, judge blocks deep..." mystatesman.com. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ^ "Texas Republicans finalize bill that would enact stiff new voting restrictions and make it easier to overturn election results". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ Platoff, Emma (April 3, 2018). ""A Friendly Vote on the Court": How Greg Abbott's Former Employees Could Help Texas from the Federal Bench". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ^ Patrick Svitek, Donald Trump endorses Gov. Greg Abbott for reelection, Texas Tribune (June 1, 2021).

- ^ Abbott, Greg (2016). Broken But Unbowed. Threshold Editions. ISBN 978-1-5011-4489-9.

- ^ Helmore, Edward (November 24, 2017). "Would-be Obama assassin identified by cat hairs, authorities say". theguardian.com. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- ^ Grinberg, Emanuella (June 6, 2017). "Texas Special Legislative Session: What's on the Agenda". CNN. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ^ "Greg Abbott: Texas Governor Revives 'Bathroom Bill' for Special Session". Fox News (from the Associated Press). June 6, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ^ Svitek, Patrick (June 6, 2017). "Gov. Abbott Calls Special Session on Bathrooms, Abortion, School Finance". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ^ McGaughy, Lauren (June 15, 2017). "Gov. Greg Abbott Vetoes 50 Bills, the Most Killed by a Texas Governor in a Decade". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ^ Svitek, Patrick (June 15, 2017). "Abbott Vetoes 50 Bills Passed by Legislature". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ^ Vertuno, Jim (March 10, 2019). "Abbott fills courts with GOP judges voters rejected". Austin American-Statesman. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Epstein, Reid J. (July 17, 2021). "In Texas, Top Two Republicans Steer Ship of State Hard to the Right". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ^ Ax, Joseph; Harte, Julia (October 13, 2021). "Texas governor moves state sharply to the right ahead of 2022 election". Reuters. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Martinez, Marissa (September 28, 2021). "Texas politics takes over American politics". Politico. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Wallace, Jeremy (January 2, 2022). "In 2021, Texas politics took a sharp right turn". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ Wallace, Jeremy (October 13, 2022). "How Gov. Abbott transformed into a culture warrior as he seeks his third term". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ Mooney, Michael (June 8, 2023). "How Ron DeSantis has outshined Greg Abbott". Axios. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ Svitek, Patrick; Barragán, James (February 28, 2023). "As 2024 nears, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis looms large over Gov. Greg Abbott in Texas". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ Trevizo, Perla; Thompson, Marilyn W. (October 25, 2022). "Greg Abbott ran as a small-government conservative. But the governor's office now has more power than ever". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Stack, Liam (November 30, 2016). "Texas Will Require Burial of Aborted Fetuses". The New York Times. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ^ Perchick, Michael (December 1, 2016). "New Texas Provisions Require Burial or Cremation of Aborted Fetuses". USA Today. KVUE. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ^ "Judge Blocks Texas Rules Requiring Burial of Fetal Remains". Fox News. December 15, 2016. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ^ Evans, Marissa (January 27, 2017). "Federal Court Blocks Texas Fetal Remains Burial Rule". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ Mekelburg, Madlin (May 26, 2017). "Sweeping Anti-Abortion Bill Heads to Gov. Greg Abbott's Desk". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ^ Grasso, Samantha (June 7, 2017). "Texas Bans Common Abortion Procedure, Requires Fetal Remains Burial with New Law". The Daily Dot. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ^ Gryboski, Michael (June 7, 2017). "Texas Governor Signs Abortion Dismemberment Ban Into Law". The Christian Post. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ^ Young, Stephen (January 30, 2018). "Federal Judge Blocks Texas' Controversial Fetal Burial Requirement". The Dallas Observer. Retrieved February 18, 2018.

- ^ "Judge halts Texas law requiring burial or cremation of fetal tissue". Reuters. January 29, 2018. Retrieved February 18, 2018.

- ^ "Abortion: Texas governor signs restrictive new law". BBC News. May 19, 2021. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ Mekelburg, Madlin. "Gov. Greg Abbott signs 'fetal heartbeat' bill banning most abortions in Texas". USA Today. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ Schreiber, Melody (September 22, 2021). "New Texas law bans abortion-inducing drugs after seven weeks pregnancy". The Guardian. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ Grissom, Brandi (January 8, 2016). "Texas Gov. Greg Abbott calls for Convention of States to take back states' rights". Dallas News.

- ^ Walters, Edgar (January 8, 2016). "Abbott Calls on States to Amend U.S. Constitution". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ "Texas Gov. Abbott Calls for Convention on Constitution, Proposes Amendments". Fox News. January 9, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ Peggy Fikac, "Governor seeks to crimp high court: Abbott wants constitutional convention," San Antonio Express-News, January 10, 2016, pp. A3, A4

- ^ Robinson, Peter (May 17, 2016). "The Texas Plan With Governor Greg Abbott". Uncommon Knowledge. Hoover Institution. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ a b McCullough, Jolie (September 9, 2020). "Gov. Greg Abbott calls on all Texas candidates to sign pledge against police budget cuts". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ McCullough, Jolie (September 3, 2020). "Gov. Greg Abbott considering legislation to put Austin police under state control after budget cut". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Garnham, Jolie McCullough and Juan Pablo (May 6, 2021). "Texas' larger cities would face financial penalties for cutting police budgets under bill approved by House". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c Eltohamy, Heidi Pérez-Moreno and Farah (June 21, 2021). "Gov. Greg Abbott vetoes criminal justice bills, legislation to protect dogs, teach kids about domestic violence". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ "Texas governor pardons former Army sergeant convicted of killing Air Force veteran during protest". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved May 18, 2024.

- ^ Hutchinson, Bill. "Soldier who killed BLM protester called 'evil' as he is sentenced to 25 years". ABC News. Retrieved May 18, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Gov. Abbott signs open carry, campus carry into law". Kvue.com. June 16, 2015. Archived from the original on January 6, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ^ a b "At Shooting Range, Abbott Signs "Open Carry" Bill". The Texas Tribune. June 13, 2015. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ^ Fernandez, Manny; Montgomery, David (December 31, 2015). "Texas Open Carry Gun Law". The New York Times. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ^ "Texas becomes 45th state to pass open carry law". Abc13.com. June 8, 2015. Archived from the original on January 4, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ^ Samuels, Alex (May 26, 2017). "Texas Governor Jokes About Shooting Reporters After Signing Gun Bill". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- ^ Siders, David (June 21, 2021). "'Tip of the spear': Texas governor leads revolt against Biden". POLITICO. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ Bowden, John (November 7, 2017). "Texas governor says church shooting should be put in context of Nazism, other horrific events". The Hill. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- ^ Feldman, Ari (November 9, 2017). "ADL Slams Texas Gov For Saying Mass Shooting Not As Bad As Hitler". Forward. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- ^ Ward, Mike (November 9, 2017). "Anti-Defamation League criticizes Abbott over 'Hitler' remark". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- ^ Greenwood, Max (May 18, 2018). "Texas gov calls for action after shooting: 'We need to do more than just pray'". Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ Montgomery, Dave; Fernandez, Manny (May 22, 2018). "Texas Governor Gathers Leaders to Talk Gun Violence: 'What Are We Going to Do to Prevent This?'". The New York Times. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- ^ Oppel, Richard A. Jr (May 30, 2018). "Texas Governor's School Safety Plan: More Armed Guards, No Big Gun Controls". The New York Times. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- ^ a b Vertuno, Jim (June 6, 2019). "Texas governor signs bill allowing more armed teachers". Associated Press. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- ^ McArdle, Mairead (June 6, 2019). "Texas Governor Signs Bill Allowing More Armed Teachers". National Review. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- ^ a b Alex Samuels, Gov. Greg Abbott lays out response to El Paso shooting but won't commit to special session, Texas Tribune (August 15, 2019).

- ^ "Texans can carry handguns without a license or training starting Sept. 1, after Gov. Greg Abbott signs permitless carry bill into law". Texas Tribune. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ "Where AR-15-style rifles fit in America's tragic history of mass shootings". NPR.org. May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ "Texas school shooting: Gunman walked in 'with handgun, possibly a rifle'; Biden was aboard Air Force One when rampage happened". Sky News. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Hooper, Kelly (May 25, 2022). "'You are doing nothing': O'Rourke accosts Abbott at press conference on shooting". Politico. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ "Gov. Greg Abbott delivers remarks at 2022 NRA Convention in Houston". Fox 26 Youtube. May 27, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ "Texas Republican decries 'pandering to idiots'". MSNBC. May 2015.

- ^ "Greg Abbott Tells Texas National Guard to Monitor U.S. Military Exercises". U.S. News & World Report.

- ^ "Texas Governor Deploys State Guard To Stave Off Obama Takeover". NPR. May 2, 2015.

- ^ "Former GOP lawmaker blisters Abbott for 'pandering to idiots' over military exercises". Trail Blazers Blog. Archived from the original on August 25, 2016. Retrieved February 3, 2017.