Kemp Mill, Maryland

Kemp Mill, Maryland | |

|---|---|

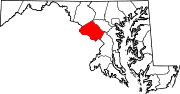

Location of Kemp Mill, Maryland | |

| Coordinates: 39°02′29″N 77°01′17″W / 39.04139°N 77.02139°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Settled | 1745 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Unincorporated |

| • County Council | Montgomery County Council |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.53 sq mi (6.57 km2) |

| • Land | 2.51 sq mi (6.50 km2) |

| • Water | 0.03 sq mi (0.07 km2) |

| Elevation | 351 ft (107 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 13,378 |

| • Density | 5,332/sq mi (2,058.36/km2) |

| Racial composition (2020)[3] | |

| • White | 59.5% |

| • Black or African American | 18.1% |

| • Asian | 8.3% |

| • Native American | 1.3% |

| • Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 13.5% |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Code | 20902, 20901 |

| Area code(s) | 301, 240 |

| FIPS code | 24-43200 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2389992[2] |

Kemp Mill is a census-designated place and an unincorporated census area in Montgomery County, Maryland, United States. It is known for its creekside walkways, calm suburban atmosphere, Brookside Gardens, and numerous hiking trails. Home to the largest Orthodox Jewish community on the East Coast between Baltimore and Miami,[4] Kemp Mill hosts more than half a dozen synagogues within its boundaries. It is commonly referred to by American Jews as a “shtetl”.[5] The population was 13,378 at the 2020 census.[6]

Kemp Mill census area consists of multiple subdivisions, including Kemp Mill Estates, Kemp Mill Farms, Kemp Mill Forest, and Springbrook Forest. The community also includes University Towers, with 523 condominium units, and the Warwick, with 393 rental units. The neighborhood has over 1,693 houses.[7]

History

Early history

Prior to the arrival of European settlers, the area that is now Kemp Mill was inhabited by Indigenous peoples, including the Piscataway and the Nacotchtank.[8] Captain John Smith of the English settlement at Jamestown was probably the first European to explore the area, during his travels along the Potomac River and throughout the Chesapeake region.[9]

Evan Thomas, a Quaker minister and political activist, settled the land and established a frame saw and grist mill in 1745, which he named Thomas’ Mill.[10] The mill was sold to Aaron Dyer in 1816, who sold it to Francis Valdenar in 1833. In the 1830s, a small settlement called Claysville sprang up around the mill. The settlement was renamed Kemp Mill in 1857 when George Kemp purchased the mill from Valdenar, and the Kemp family managed the mill until 1905. The mill eventually burned down in 1919, marking the end of 174 years of continuous operation.[11]

19th century

In the nineteenth century, much of eastern Montgomery County was dominated by agriculture. The area's rolling terrain was ideal for both small and large farms, while the surrounding woodlands provided essential lumber for homes. Early settlers also established mills along the Northwest Branch Anacostia River and Paint Branch, utilizing the streambed gradient to harness hydropower.[12]

In July 1864, during the Civil War, Silver Spring, Maryland (including Kemp Mill) experienced a significant incursion by Confederate forces. As General Jubal Early's troops spread across the fields and orchards, reactions among the residents varied, with some cheering, and others fleeing to the capital. The Confederate soldiers ransacked properties, including the estate of Montgomery Blair, Lincoln's postmaster general, which they set ablaze. Additionally, Early used the home of Blair's father as his headquarters to coordinate an assault on Washington's defenses.[13]

20th century

The first subdivisions in the greater Kemp Mill area broke ground in 1931.[10] During this era, the nearby Washington suburb of Silver Spring has been described as a sundown town.[14] Prior to the Second World War, racial covenants were used in Washington, D.C. and Silver Spring to exclude African Americans, Jews, and others.[15][16] In 1948, the Supreme Court Shelley v Kraemer decision rendered racial covenants legally unenforceable, but African Americans, Jews, and others in the Washington metropolitan area continued to be excluded under the covenants until the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968.[8][17]

In the early 1930’s, property owners in the Kemp Mill area began establishing very large lot subdivisions (five-acre lots) in various areas just outside the initial suburban ring. These developments were intended to be exclusive neighborhoods with a park-like ambiance. Gray's Estates in Kemp Mill was one such example. Yeatman Parkway, following a tributary to the Northwest Branch, was dedicated as part of Gray's Estates. Today, the parkway is the only remnant of this type of development in Kemp Mill.[12]

A few years after World War II, developers plotted subdivisions with one to five-acre lots near the stream valley parks, anticipating future access to planned sewer systems, as noted on the record plats. Springbrook Forest in Kemp Mill, adjacent to the future Northwest Branch Park, dates back to this phase of suburban expansion.[12]

Kemp Mill Farms and Kemp Mill Estates were first developed in the late 1950s,[18] approximately a decade after the 1948 Supreme Court Shelley v Kraemer decision. The neighborhood was among several communities in Montgomery County's Silver Spring area that were built by Jewish real estate developers catering to Jews moving to the suburbs from Washington, D.C.[16] The majority of residences in Kemp Mill are single family homes dating to the 1950s, although newer homes were built in the 1980s and 1990s on Yeatman, Bromley, and Kersey roads.[19]

Kemp Mill Estates was developed by Jack Kay and Harold Greenberg of the Kay Construction Company, the son and son-in-law of real estate developer Abraham S. Kay.[18] At the time of its development, it was located outside of an area of Silver Spring that had been historically closed to Jews.[20] According to the historian David Rotenstein, some Jewish developers in Silver Spring, including the Kays, used anti-Black covenants prior to the Fair Housing Act of 1968. As he said, “to be sure, Jews were barred from many places, too, but our shared Judaism doesn’t immunize us from racism.” However, Rotenstein acknowledged that some Jewish developers also built integrated housing. For example, Morris Milgram began purchasing existing apartments in Silver Spring and integrating them during the early and mid-1960s, and Jewish organizations such as Jews for Urban Justice formed to protest alongside civil rights groups, advocating for equal access to housing.[21]

In the late 1970s, the average price of a home in Kemp Mill was between $85,000 and $90,000. In 1978, a black DC school official living in Kemp Mill was the target of a hate crime when the N-word and "KKK" were painted on her house and her tires were slashed.[22]

Orthodox Jews began moving to Kemp Mill in 1961, when the Young Israel Shomrai Emunah synagogue relocated from Washington, D.C.[23] In 1989, 25% of the 2,000 families in Kemp Mill were Orthodox Jews.[24] A 2005 Washington Post article stated that half of the community's 10,000 residents were Orthodox Jews.[23]

To support their religious practices, Orthodox Jews in Kemp Mill developed tight-knit communities and constructed eruvim, ritual boundaries that allow for the carrying of objects on Shabbat. These eruvim were creatively made using utility poles, freeway barriers, fences, and strings. An eruv inspector, often seen in tzitzit, kippah, and an orange vest, checks the eruv on Thursdays or Fridays to ensure it is kosher. According to historian David Rotenstein, “there are signs of Jewish adaptations to the landscape everywhere if you know where to look”.[21]

In March 1989, a young Asian man was beaten in nearby Sligo Creek Park by a group of youths and young adults shouting anti-Asian racial slurs. Ten individuals were arrested related to the crime. That same year, there was a spate of antisemitic incidents rumored to be due to skinheads. Swastikas were painted on several vehicles, 40 cars had their windows shot in with BB guns, the graffiti "All Jews Must Die Now" was painted on a sidewalk, and an Orthodox Jewish school was vandalized.[24] A suspect was tried for vandalizing the Orthodox Jewish school after he confessed to the crime to ten people over several months, according to trial testimony. However, police found no physical evidence linking the suspect to the crime, and nobody was convicted. At the time, authorities described the incident at the school as "extraordinarily destructive."[25]

A community meeting was held and the local police claimed that "youths" were to blame for the antisemitic incidents and that there were no organized neo-Nazis or skinheads in the region. However, a man living in Kemp Mill had recently been convicted for antisemitic vandalism of the Kemp Mill Urban Park, an act the police claimed was inspired by the 1988 film Betrayed, which follows the actions of a white supremacist organization.[24]

21st century

During the summer of 2020, multiple Black Lives Matter rallies were held at Northwood High School in Kemp Mill as part of the nationwide protests against racism and police brutality. [26] A 2020 statement of solidarity with African Americans issued by the Jewish Community Relations Council of Greater Washington was signed by Kemp Mill Synagogue.[27]

In June 2022, shortly before the Shavuot holiday, antisemitic fliers advertising neo-Nazi websites were placed at several locations in Kemp Mill, including at a bus shelter located in front of the Young Israel Shomrai Emunah synagogue and on an ice chest outside of the Shalom Kosher grocery store. The fliers used antisemitic slurs, denied the Holocaust, and called for genocide against the Jewish People.[28][29][30]

In February 2023, Northwood High School's outdoor facilities were closed to the public due to repeated targeting by an unknown hate group with antisemitic fliers. The fliers were found on the school's athletic fields four times, prompting Principal Jonathan Garrick to announce the closure of the facilities, including the athletic fields, track, tennis courts, and other outdoor areas. Although the perpetrators were not apprehended, the GDL had recently been caught vandalizing Jewish properties in nearby Kensington, Maryland.[31] A month later, the ADL reported a 261% spike in antisemitic incidents across Montgomery County over the year, with a concentration of these incidents occurring in Kemp Mill. The county accounted for nearly 60% of antisemitic incidents reported in the state of Maryland in 2022.[32]

In September 2023, multiple reports surfaced of blue-eyed Himalayan cats being found in the Kemp Mill area. The sudden appearance of these rare cats, many of which were in poor health, led to a state-wide media frenzy. The exact origin of the cats was never uncovered, and animal welfare organizations were called upon to help manage the influx.[33]

Following the Simchat Torah Massacre in Israel on October 7, 2023, after a notable uptick in anti-Semitic vandalism was seen in Kemp Mill, the Montgomery County police announced on October 9, 2023, that they were stepping up patrols around synagogues and Jewish schools in the county.[34]

Culture

The Kemp Mill area, with its small size and the frequent use of local amenities by residents, has developed into a pedestrian-friendly community. Many people walk to nearby shops, schools, religious institutions, and recreational spots. Each sub-neighborhood within Kemp Mill has its unique character, shaped by similar housing styles and separated by local streets.[35] Most of the residential streets of Kemp Mill consist of winding roads ending in cul-de-sacs. The area features a mix of midcentury split-level homes, 1980s colonials, and ramblers, all set behind sidewalks and grassy front lawns, shaded by oak trees. In 2024, home prices in the neighborhood ranged from $480,000 to $1.3 million.[36]

To the north are Kemp Mill Forest and Springbrook Forest. Kemp Mill Forest, developed in the 1980s using a cluster design, includes both single-family homes and townhouses. Springbrook Forest, one of the oldest neighborhoods, features large lots, narrow streets, and numerous mature trees. The central Kemp Mill neighborhood dates back to the 1950s and 1960s, characterized by traditional suburban development with lots ranging from 6,000 to 9,000 square feet, featuring brick houses.[35]

Kemp Mill is home to the largest Orthodox Jewish community on the East Coast between Baltimore and Miami.[4] It hosts a number of synagogues serving Orthodox Jews (Modern Orthodox, Hasidic, and Yeshivish) including Young Israel Shomrai Emunah, the Yeshiva of Greater Washington (Tiferes Gedaliah), Chabad of Silver Spring, Kemp Mill Synagogue, Silver Spring Jewish Center, Kehillas Ohr Hatorah and Minchas Yitzhak. Additionally, there are many smaller Orthodox Jewish minyanim (prayer groups) throughout the neighborhood including a Sephardic Minyan that meets at Shomrai Emunah and the Lower Lamberton Minyan.

There are also a number families in the area who are served by a Conservative synagogue, Har Tzeon Agudath Achim.

Several Jewish parochial schools are located in Kemp Mill including the Silver Spring Learning Center, the Jewish Montessori School, and the boys division of the Yeshiva of Greater Washington. The yeshiva also hosts a kollel (Zichron Amram) and a yeshiva gedolah, which offers a Bachelor's degree in Talmudic Law through its fully accredited college program, Yeshiva College of the Nation's Capital.

Three public schools are also situated in the area, including Northwood High School, Odessa Shannon Middle School (Renamed from Colonel E. Brooke Lee Middle School in July 2021), and Kemp Mill Elementary School. The former Spring Mill Elementary school is now the Yeshiva Middle School and an administrative office.[37]

Kemp Mill Shopping Center, along with the public amenities of Kemp Mill Urban Park, collectively function as the community's town center. Sidewalks from the neighboring residential developments lead to the shopping center, and a paved trail from Sligo Creek Park also terminates at this central location.[35]

The shopping center is the commerce hub of the neighborhood. It was long anchored by Giant Food, which operated there until September 27, 2007. On November 7, 2007, Magruder's, a local grocery chain, opened in its place but closed in July 2012 when Shalom Kosher purchased it. Shalom Kosher opened on October 31, 2012. Besides the grocery store, Kemp Mill Center includes Ben Yehuda Cafe and Pizzeria, The Kosher Pastry Oven, CVS Pharmacy, MVA - Kemp Mill, Nova Europa Restaurant, Holy Chow!, MoneyGram, Truist, Cartronics ATM, Kemp Mill Beer & Wine, U-Haul Neighborhood Dealer, Bright Star Nails, Kemp Mill Dry Cleaners, and Kemp Mill Optical.[38]

A Kemp Mill Village is being formed to serve the needs of elderly and disabled residents. Montgomery County has established the position of Village Coordinator to assist communities with establishing villages.

Crime

Kemp Mill has a crime rate of 12.24 incidents per 1,000 residents annually, making it safer than 90% of U.S. cities. Violent crime is low, with a rate of 1.56 per 1,000 residents, while property crime, albeit rare, is slightly more common, at 6.91 per 1,000 residents. The northeast part of Kemp Mill is generally considered the safest, while the southwest has slightly higher crime rates.[39]

In comparison to nearby areas, Kemp Mill has a lower crime rate than the majority of neighborhoods, including Four Corners, White Oak, Woodside and Wheaton. This means residents of Kemp Mill experience fewer incidents of both violent and property crimes relative to many surrounding communities.[39]

Recreation

The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission's Kemp Mill Recreation Center offers users baseball diamonds, basketball and tennis courts, an indoor ice-skating rink, a meeting space, a playground, and a dog park. Sligo Creek rises in Kemp Mill, and the hiker-biker trail that runs alongside the creek from Wheaton Regional Park to the Anacostia River passes through the community. There is also a trail for riding horses. Equestrians can board their horses, ride and take lessons.

The eastern end of Kemp Mill is bounded by the Northwest Branch Anacostia River, which also flows south to the Anacostia and is a popular hiking trail to Route 29 Colesville Road or Brookside Gardens.

Deer are a frequent sight in the neighborhood, along with red foxes. Numerous bird species nest in the CDP and along the Northwest Branch, including red-shouldered hawks, owls, northern cardinals, blue jays, black rails (endangered), american robins, northern mockingbirds, sedge wrens (endangered), baltimore orioles, mourning warblers (endangered), gray catbirds, carolina chickadees, carolina wrens, white-breasted nuthatches, swainson's warblers (endangered), tufted titmuoses, loggerhead shrikes (endangered), and northern flickers. American crows and turkey vultures are also present.

Kemp Mill Urban Park sits on 2.7 acres of centrally-located land directly off of Arcola Avenue, wedged between the Yeshiva of Greater Washington, Young Israel Shomrai Emunah, and the Kemp Mill Shopping Center. It provides a playground, basketball court, and meeting place. It includes a large water feature that is traversed by flocks of geese, ducks, and swans. Originally developed in the 1960s, the park was temporarily closed in February 2016 for renovations and reopened in May 2017.

Wheaton Library and Recreation Center, commissioned by the Montgomery County Public Libraries (MCPL), is just a two-minute drive up Arcola Avenue, on the corner of Georgia Avenue.

Two private swimming pools, Parkland Pool and Kemp Mill Swim Club, serve the community.

Geography

Large parks border Kemp Mill on both the east and west sides. A defining feature of Kemp Mill is its abundant open space and greenery. Extensive stretches along both sides of Kemp Mill Road are filled with lush greenery. Northwest Branch Anacostia River lies to the east, while Wheaton Regional Park is to the west. The Kemp Mill area contains around 6,000 acres of forest, most of which is situated within parkland.[10]

As an unincorporated area, Kemp Mill does not have officially defined boundaries. However, Kemp Mill is recognized by the United States Census Bureau and by the United States Geological Survey as a census-designated place.[40]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the neighborhood has a total area of 2.54 square miles (6.2 km2), nearly all land.

Kemp Mill is considered by many of its residents to be part of unincorporated Silver Spring.[41] It is served by the Wheaton Post Office.

There is a very large eruv that encompasses Kemp Mill and the other Jewish communities of Silver Spring.[42]

Climate

Kemp Mill experiences a humid subtropical climate, characterized by hot, humid summers and mild winters. Summer temperatures typically reach the mid-80s Fahrenheit, while winter temperatures seldom drop below freezing. The area receives an average of 44 inches of rain annually, surpassing the U.S. average of 38 inches per year. Precipitation is distributed relatively evenly throughout the year, with slightly drier conditions during the summer months.[43]

Snowfall in Kemp Mill averages 14 inches per year, which is lower than the national average of 28 inches. Precipitation of some form occurs approximately 110 days per year.[43]

July is the hottest month in Kemp Mill, with an average high temperature of 87.5°F, making it warmer than most locations in Maryland. The area enjoys three particularly comfortable months—September, May, and June—where high temperatures range between 70-85°F.[43]

The summer months in Kemp Mill can bring uncomfortable levels of humidity, with July being the most humid. However, humidity levels remain low for much of the year, with July, August, and June being the most humid months.[43]

Transportation

Kemp Mill is serviced by Ride On bus numbers 8, 9 and during rush hours, number 31, as well as Metrobus numbers C2 and C4. Washington Metro service on the Red Line is also available in the nearby Wheaton Metro Station and Silver Spring Metro Station.

Education

Montgomery County Public Schools operates public schools.

Kemp Mill Elementary School, Odessa Shannon Middle School and Northwood High School are all within the Kemp Mill CDP.[44]

Kemp Mill is a highly educated community, with 92.5% of the population having a high-school diploma or higher and 60.2% holding a bachelor's degree or higher (as of 2020).

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 9,956 | — | |

| 2010 | 12,564 | 26.2% | |

| 2020 | 13,378 | 6.5% | |

| source:[45][46] 2010–2020[6] | |||

2020 Census

As of the 2020 United States Census,[6] there were 13,378 persons residing in the area. Persons under 18 years of age made up 24.9% of the area, while those over 65 years of age accounted for 16.1%. The population density was 5,332 inhabitants per square mile. The racial makeup of the area was 59.5% White, 18.1% Black, 8.3% Asian, and 1.3% American Indian. Hispanics and Latinos of any race were 13.5% of the population. Non-Hispanic Whites were 55.1% of the population. Foreign-born persons accounted for 27.1% of the population, and 34.8% spoke a language other than English at home, including Russian, Ukrainian, Hebrew, Yiddish, and Spanish.

In 2020, there were 4,713 households, of which 83.7% was owner-occupied. The median value of owner-occupied housing units was $518,100. Median household income in the CDP was $151,943 and per capita income was $60,348. 69.6% of the population aged 16 or older was in the civilian labor force. The poverty level was 6.9% of the population.

2010 Census

As of the 2010 United States Census,[47] there were 12,564 people and 4,430 households residing in the area. The population density was 4,952.3 inhabitants per square mile (1,912.1/km2). The racial makeup of the area was 61.7% White, 19.5% African American, 1% Native American, 5% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, and 3.7% of mixed race. Hispanics and Latinos of any race were 18.6% of the population. Non-Hispanic whites were 54.8% of the population.

There were 3,386 households, out of which 33.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 65.3% were married couples living together, 9.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 21.6% were non-families. 17.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.89 and the average family size was 3.22. Twenty-seven percent of Kemp Mill residents hold a graduate degree.

In the area, the population was spread out, with 25.1% under the age of 18, 5.6% from 18 to 24, 25.9% from 25 to 44, 24.7% from 45 to 64, and 18.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 41 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 91.5 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $89,294, and the median income for a family was $111,985. Males had a median income of $52,244 versus $41,285 for females. The per capita income for the area was $34,570. About 2.3% of families and 4.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 2.6% of those under age 18 and 1.7% of those age 65 or over.

A large number of Russian-Jewish immigrants have settled in Kemp Mill, particularly since the 1980s.[48] Due to the large Ethiopian and Jewish populations in Silver Spring and Washington, D.C.,[49] Kemp Mill is home to a sizeable community of Beta Israel (Ethiopian Jews).

Notable people

A

- HaRav Gedaliah Anemer (1932–2010), founder of the Yeshiva of Greater Washington, posek

- Michael Auslin (b. 1967), historian, columnist, author

B

- Jonathan Banks (b. 1947), television and film actor

- Alex Bazzie (b. 1990), NFL player

- Erica Brown (b. 1966), writer and educator

C

- Jerry Ceppos (1946-2022), journalist and academic

- Norman Chad (b. 1958), sportswriter, poker broadcaster, columnist for ESPN

- Eliot A. Cohen (b. 1956), political scientist, counselor in the United States Department of State (2007-2009)

D

- George Daly, music executive

- Matt Drudge (b. 1966), creator and editor of the Drudge Report, author

G

- Shlomo Gaisin, singer and songwriter

H

- Josh Hart (b. 1995), NBA Player

J

- Richard Joel (b. 1950), president of Yeshiva University

K

- Jan Rose Kasmir, cultural icon, subject of historic picture at 1967 March on the Pentagon

- Samuel Kotz (1930–2010), mathematician and statistician

- H. David Kotz (b. 1966), Inspector General of the Peace Corps (2006–2007), Inspector General for the Securities and Exchange Commission (2007–2012)

- Benjamin F. Kramer (b. 1957), politician

- Rona E. Kramer (b. 1954), politician

- Sidney Kramer (1925–2002), politician, businessman, and philanthropist

- Daniel Kurtzer (b. 1949), U.S. Ambassador to Egypt (1997–2001), U.S. Ambassador to Israel (2001–2005)

- Yehuda Kurtzer (b. 1977), President of the Shalom Hartman Institute

L

- Annie Leibovitz (b. 1949), photographer and visual artist

- Dov Lipman (b. 1971), member of the Knesset (2013–2015)

- Rav Aaron Lopiansky, Rosh HaYeshiva of Tiferes Gedaliah (YGW), Jewish scholar, author, and educator

M

- David Makovsky (b. 1960), foreign policy scholar, author, journalist

- Louis Mayberg, entrepreneur and philanthropist

- Rabbi Yitzchok Merkin, leader of Torah Umesorah – National Society for Hebrew Day Schools

- Nicolas Muzin, political strategist

P

- George Pelecanos (b. 1957), author (detective and noir fiction), television producer and a television writer (The Wire)

R

- Evelyn Rosenberg (b. 1948), international artist, creator of the detonography method

- Azriel Rosenfeld (1931–2004), computer scientist and mathematician, pioneer of computer image analysis

S

- Saul Jay Singer (b. 1951), legal ethicist and The Jewish Press columnist

- Matthew H. Solomson (b. 1974), judge of the United States Court of Federal Claims (2020–present)

T

- Tevi Troy (b. 1967), U.S. Deputy Secretary of Health and Human Services (2007–2009)

Z

- Dov S. Zakheim (b. 1948), businessman, writer, Comptroller of the Department of Defense (2001–2004)

References

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Kemp Mill, Maryland

- ^ "QuickFacts Kemp Mill CDP, Maryland".

- ^ a b "Tightly knit Kemp Mill". The Washington Examiner. May 26, 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ [1], Kemp Mill Synagogue Gala Banquet 2020

- ^ a b c "QuickFacts: Kemp Mill CDP, Maryland". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- ^ "Where We Live: Kemp Mill". Washington Post. April 15, 2023. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved October 4, 2024.

- ^ a b "University Boulevard Corridor Plan" (PDF). Montgomery Planning. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ Sween, Jane C.; Offutt, William (1999). Montgomery County: Centuries of Change : An Illustrated History. American Historical Press. ISBN 978-1-892724-05-2.

- ^ a b c Kemp Mill Master Plan Introduction (PDF), retrieved July 3, 2024

- ^ [2], The Historical Marker Database

- ^ a b c MNCPPC Report, retrieved July 3, 2024

- ^ Available Now - Silver Spring and the Civil War - Maryland's Digital Library - OverDrive, retrieved June 20, 2024

- ^ Rotenstein, David S. (June 23, 2017). "Protesting Invisibility in Silver Spring, Maryland". The Activist History Review. Retrieved October 4, 2024.

- ^ Shaver, Katherine (December 20, 2022). "Was your home once off-limits to non-Whites? These maps can tell you". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved October 4, 2024.

- ^ a b "Exodus: Why DC's Jewish community left the central corridors, then came back". Greater Greater Washington. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ [3], MOCO 360

- ^ a b ""Jack Kay, 87, D.C. area home builder and philanthropist"". The Washington Post. April 24, 2014.

- ^ "'50s flashback: Kemp Mill houses have artifacts within their walls". July 7, 2021.

- ^ "Downtown Silver Spring: Inclusivity Examined since 1940". December 3, 2019.

- ^ a b Monicken, Hannah (November 10, 2017). "Silver Spring's Jewish history 'long and complicated'". Washington Jewish Week. Archived from the original on August 25, 2018. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ^ "Racial Epithets Painted Upon Officials' House". Washington Post. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- ^ a b Rathner, Janet (October 14, 2005). "An Orthodox Destination". Washington Post. Retrieved April 20, 2024.

- ^ a b c Pressley, Sue Anne (September 16, 1989). "Hatred Intrudes on Community". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- ^ Kyriakos, Marianne (December 26, 1992). "Kemp Mill: Neighborhood Holds To Religious Past". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 4, 2024.

- ^ "Hundreds gather at Northwood High for peaceful protest of police brutality". Bethesda Magazine. June 4, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- ^ "Solidarity Statement Sign On". Jewish Community Relations Council of Greater Washington. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ "Antisemitic flyers discovered at bus stop in Kemp Mill". Bethesda Magazine. Retrieved May 3, 2022.

- ^ "Swastika flier found at bus stop across from Maryland synagogue". Jewish News Syndicate. June 2, 2022.

- ^ "Swastika Posted at Bus Stop by Silver Spring Synagogue". Montgomery County Media. Retrieved May 3, 2022.

- ^ "Antisemitism in Montgomery County Schools". The Washington Post. March 2, 2023.

- ^ [4], MoCo360

- ^ Gray, Anita (September 16, 2023). "Waves of Lost Blue-Eyed Himalayan House Cats Keep Flooding Into Maryland Neighborhoods". Cole and Marmalade. Retrieved September 12, 2024.

- ^ Roussey, Tom (October 9, 2023). "Montgomery County police increase patrols around Jewish institutions amid Israel, Hamas conflict". wjla.com. Retrieved October 4, 2024.

- ^ a b c Kemp Mill Master Plan 2001 (PDF), retrieved July 3, 2024

- ^ "Kemp Mill Neighborhood Guide". Homes.com. Retrieved August 30, 2024.

- ^ "Boys Education, Mesivta, Dual Curriculum". www.yeshiva.edu. Retrieved October 4, 2024.

- ^ "Kemp Mill, MD: History, Population and Facts About the Area". bkinjurylawyers.com/. May 30, 2021. Retrieved October 4, 2024.

- ^ a b "Safest Places in Kemp Mill, MD". CrimeGrade.org. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Jewish Silver Spring". Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ^ [Kemp Mill Synagogue], [5]

- ^ a b c d Kemp Mill, MD Climate. BestPlaces. Retrieved August 13, 2024.

- ^ "2010 CENSUS - CENSUS BLOCK MAP: Kemp Mill CDP, MD" (Archive). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on June 22, 2015.

- ^ "CENSUS OF POPULATION AND HOUSING (1790-2000)". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- ^ Community not enumerated separately in 1980 & 1990. Kemp Mill was part of Silver Spring's census area.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Richburg, Keith B. (November 14, 1981). "Silver Spring: Home of Ethnic Diversity". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ Belitsky, Helen Mintz (September 10, 1993). "Ethiopian Jews Find a Home in Northwest". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

External links

- Kemp Mill, Maryland

- Ashkenazi Jewish culture in Maryland

- Census-designated places in Maryland

- Census-designated places in Montgomery County, Maryland

- Ethiopian-Jewish culture in the United States

- Haredi Judaism in the United States

- Hasidic Judaism in the United States

- Israeli-American history

- Modern Orthodox Judaism in Maryland

- Neighborhoods in Montgomery County, Maryland

- Orthodox Jewish communities

- Orthodox Judaism in Maryland

- Russian-Jewish culture in Maryland

- Polish-Jewish culture in Maryland

- Lithuanian-Jewish culture in Maryland

- Ukrainian-Jewish culture in Maryland

- Sephardi Jewish culture in Maryland

- Wheaton, Maryland

- Yiddish culture in Maryland