Stephenson's Rocket

| Rocket | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

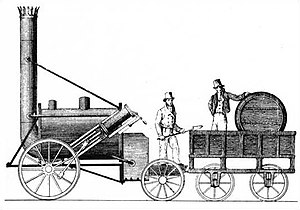

A contemporary drawing of Rocket | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stephenson's Rocket is an early steam locomotive of 0-2-2 wheel arrangement. It was built for and won the Rainhill Trials of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&MR), held in October 1829 to show that improved locomotives would be more efficient than stationary steam engines.[7]

Rocket was designed and built by Robert Stephenson in 1829, and built at the Forth Street Works of his company in Newcastle upon Tyne.

Though Rocket was by no means the first steam locomotive, it was the first to bring together several innovations to produce the most advanced locomotive of its day. It is the most famous example of an evolving design of locomotives by Stephenson that became the template for most steam engines in the following 150 years.

The locomotive was preserved and displayed in the Science Museum in London until 2018, after which it was briefly exhibited at various sites around the U.K. until it came to rest at the National Railway Museum in York. Since 2023, it has been based at the Locomotion Museum in Shildon.[8]

History

[edit]Prior developments

[edit]Rocket was built at a time of rapid development of steam engine technology. It was based on experience gained from earlier designs by George and Robert Stephenson, including the Killingworth locomotive Blücher (1814); Locomotion (1825); and the Lancashire Witch (1828).

Conception

[edit]There have been differences in opinion on who should be given the credit for designing Rocket. George Stephenson had designed several locomotives before but none as advanced as Rocket. At the time that Rocket was being designed and built at the Forth Banks Works, he was living in Liverpool overseeing the building of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. His son Robert had recently returned from a stint working in South America and resumed as managing director of Robert Stephenson and Company. He was in daily charge of designing and constructing the new locomotive. Although he was in frequent contact with his father in Liverpool and probably received advice from him, it is difficult not to give the majority of the credit for the design to Robert. A third person who may deserve a significant amount of credit is Henry Booth, the treasurer of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. He is believed to have suggested to Robert Stephenson that a multi-tube boiler should be used.[9][10]

Stephenson designed Rocket for the Rainhill trials, and the specific rules of that contest. As the first railway intended for passengers more than freight, the rules emphasised speed and would require reliability, but the weight of the locomotive was also tightly restricted. Six-wheeled locomotives were limited to six tons, four-wheeled locomotives to four and a half tons. In particular, the weight of the train expected to be hauled was to be no more than three times the actual weight of the locomotive. Stephenson realised that whatever the size of previously successful locomotives, this new contest would favour a fast, light locomotive of only moderate hauling power.[11]

Rainhill trials

[edit]On 20 April 1829, the board of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway project passed a resolution for a competition to be held to prove their railway could be reliably operated by steam locomotives, there being advice from eminent engineers of the age that stationary engines would be required.[12] A prize of £500 was offered as an incentive to the winner, with strict conditions a locomotive would need to meet to enter the trial.[13] Robert Stephenson was able to report to Henry Booth on 5 September 1829 that Rocket[a] had performed initial manufacturer tests with flying colours at Killingworth. Rocket was dismantled at Newcastle and began the long trip to Rainhill: by horse wagon to Carlisle; lighter to Port Carlisle then by the Cumberland steamer to Liverpool for re-assembly on 18 September 1829.[15][16] Rocket passed the trial requirement of achieving an average speed of 10 mph (16 km/h) over 70 miles (110 km) by over 40 percent.[17] Demonstrations also saw Rocket consistently and easily haul a carriage with over 20 persons up the Whiston Incline at over 15 mph (24 km/h), and light engine running of around 30 mph (48 km/h).[17] No other locomotive at the trials was able to achieve anything like the level of performance reliably, with partners Booth and Stephensons sharing the £500 winnings, and perhaps more importantly the need for stationary engines being demonstrated as unnecessary with sceptics such as Rastrick on the way to conversion.[18]

Operation

[edit]

The opening ceremony of the L&MR on 15 September 1830 was a considerable event, drawing luminaries from the government and industry, including the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington. The day started with a procession of eight trains setting out from Liverpool for Manchester. The parade was led by Northumbrian driven by George Stephenson, and included Phoenix driven by his son Robert, North Star driven by his brother Robert Sr. and Rocket driven by assistant engineer Joseph Locke. The day was marred by the death of William Huskisson, the Member of Parliament for Liverpool, who was struck and killed by Rocket at Parkside.[9]

History between 1830 and 1840 is only vaguely documented. From 1830 to 1834, Rocket served on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway.

After service on the L&MR, Rocket was used between 1836 and 1840 on Lord Carlisle's Railway near Brampton, in Cumberland (now Cumbria), England.[19][20]

Built as a prototype to win a speed trial, the engine was soon superseded by improved designs, such as Stephenson's Northumbrian and Planet designs, both of 1830.

Within a few years, the Rocket itself had been much modified to be similar to the Northumbrian class. The cylinders were altered to a near-horizontal position, compared to the angled arrangement as new; the firebox capacity was enlarged and the shape simplified; and the locomotive was given a drum smokebox.[21] These arrangements can be seen in the engine today. Such are the changes in the engine from 1829 that The Engineer magazine, circa 1884, concluded that "it seems to us indisputable that the Rocket of 1829 and 1830 were totally different engines".[22]

In 1834, the engine was selected for further (unsuccessful) modifications to test a newly developed rotary steam engine designed by Admiral The 10th Earl of Dundonald.[23] At a cost of nearly £80, Rocket's cylinders and driving rods were removed and two of the engines were installed directly on its driving axle with a feedwater pump in between. On 22 October, of that year, an operational trial was held with disappointing results; one witness observing, that "the engine could not be made to draw a train of empty carriages". Due to inherent flaws and engineering difficulties associated with their design, Lord Dundonald's engines were simply too underpowered for the task.[24]

In 1836, Rocket was sold for £300 and began service on the Brampton Railway, a mineral railway in Cumberland that had recently converted to Stephenson gauge.[25] It remained here at Tindale, after service, until 1862 and its donation to the Patent Office Museum, London.

Preservation

[edit]In 1862, Rocket was donated to the Patent Office Museum in London (now the Science Museum)[1] by the Thompsons of Milton Hall, near Brampton.[26]

The locomotive still exists, though it has not been operated since becoming a museum exhibit. It was displayed at the Science Museum for 150 years, although in a form much modified from its state at the Rainhill Trials. In 2018, it was displayed first in Newcastle[27] and then in Manchester at the Science and Industry Museum from 25 September 2018 to 8 September 2019.[28] From 2019, it was displayed at the National Railway Museum, York,[27][29] and is currently housed at Locomotion Museum in Shildon, County Durham, since 2023.

Design

[edit]

The locomotive had a tall 16 ft smokestack chimney at the front, a cylindrical boiler in the middle, and a separate firebox at the rear. The large front pair of wooden wheels was driven by two external cylinders set at an angle of 38°. The smaller rear wheels were not coupled to the driving wheels, giving an 0-2-2 wheel arrangement.[9] One of the cylinders drove a small 1.25 inch diameter feedwater pump which pumped water from the tender to the boiler, a valve could be adjusted to control the amount of water needed.

Driving wheels

[edit]Stephenson's most visible decision was to use a single pair of driving wheels, with a small carrying axle behind. This was the first 0-2-2 and first single driver locomotive.[b][30] The use of single drivers gave several advantages. The weight of coupling rods was avoided and the second axle could be smaller and lightweight, as it only carried a small portion of the weight. Rocket placed just over 2+1⁄2 tons of its 4+1⁄2 ton total weight onto its driving wheels,[31] a higher axle load than Sans Pareil, even though the 0-4-0 was heavier overall at 5 ton, and officially disqualified by being over the 4+1⁄2 ton limit.[30] Early locomotive designers had been concerned that the adhesion of a locomotive's driving wheels would be inadequate, but Stephenson's past experience convinced him that this would not be a problem, particularly with the light trains of the trials contest.

Boiler

[edit]Rocket uses a multi-tubular boiler design. Previous locomotive boilers consisted of a single pipe surrounded by water (though the Lancashire Witch did have twin flues). Rocket had 25 copper[32] fire-tubes that carried the hot exhaust gas from the firebox, through the wet boiler to the blast pipe and chimney. This arrangement resulted in a greatly increased surface contact area of hot pipe with boiler water when compared to a single large flue. Additionally, radiant heating from the enlarged separate firebox helped deliver a further increase in steaming and hence boiler efficiency.

The original innovator of multiple fire-tubes is unclear, between Stephenson and Marc Seguin. It is known that Seguin visited Stephenson to observe Locomotion and that he also built two multi-tubular locomotives of his own design for the Saint-Étienne–Lyon railway before Rocket. Rocket's boiler was of the more highly developed form, with the separate firebox and a blastpipe for draught, rather than Seguin's cumbersome fans, but Rocket was not the first multi-tubular boiler, although it remains unclear just whose invention it was.

The benefits of increasing the fire-tube area had also been attempted with Ericsson and Braithwaite's Novelty at Rainhill. Their design though used a single fire-tube, folded in three. This offered an increased surface area, but only at the cost of a proportionately increased length and so poor draught on the fire. Its arrangement also made tube cleaning impractical.

The advantages of the multiple-tube boiler were quickly recognised, even for heavy, slow freight locomotives. By 1830, Stephenson's past employee Timothy Hackworth had re-designed his return-flued Royal George as the return-tubed Wilberforce class.[33]

Blastpipe

[edit]Rocket also used a blastpipe, feeding the exhaust steam from the cylinders into the base of the chimney so as to induce a partial vacuum and pull air through the fire. Credit for the invention of the blastpipe is disputed, though Stephenson used it as early as 1814.[34] The blastpipe worked well on the multi-tube boiler of Rocket but on earlier designs with a single flue through the boiler it had created so much suction that it tended to rip the top off the fire and throw burning cinders out of the chimney, vastly increasing the fuel consumption.[9]

Cylinders and pistons

[edit]

Like the Lancashire Witch, Rocket had two cylinders set at angle from the horizontal, with the pistons driving a pair of 4 feet 8.5 inches (1.435 m) diameter wheels.[35] Most previous designs had the cylinders positioned vertically, which gave the engines an uneven swaying motion as they progressed along the track. Subsequently, Rocket was modified so that the cylinders were set close to horizontal, a layout that influenced nearly all designs that followed.

Again like the Lancashire Witch, the pistons were connected directly to the driving wheels, an arrangement which is found in subsequent steam locomotives.[1]

Firebox

[edit]The firebox was separate from the boiler and was double walled, with a water jacket between them. Stephenson recognised that the hottest part of the boiler, and thus the most effective for evaporating water, was that surrounding the fire itself. This firebox was heated by radiant heat from the glowing coke, not just convection from the hot exhaust gas.

Locomotives of Rocket's era were fired by coke rather than coal. Local landowners were already familiar with the dark clouds of smoke from coal-fired stationary engines and had imposed regulations on most new railways that locomotives would 'consume their own smoke'.[11] The smoke from a burning coke fire was much cleaner than that from coal. It was not until 30 years later and the development of the long firebox and brick arch that locomotives would be effectively able to burn coal directly.

Rocket's first firebox was of copper sheet and of a somewhat rectangular shape from the side.[36] The throatplate was of firebrick, possibly the backhead too.[37] When rebuilt around 1831,[37] this was replaced by a wrought iron backhead and throatplate, with a drum wrapper (now missing), presumed to be of copper, between them. This gave a larger internal volume and encouraged better combustion within the firebox, rather than inside the tubes. These early fireboxes formed a separate water space from the boiler drum and were connected by prominent external copper pipes.

Other Rocket-type locomotives

[edit]Rocket was followed by a number of other engines of similar 0-2-2 layout with rear-mounted cylinders built for the L&MR before it opened on 15 September 1830, culminating in the Northumbrian (1830), by which time the cylinders were horizontal. Other engines of the Rocket design which were delivered to the Liverpool and Manchester railway included Arrow, Comet, Dart and Meteor, all being delivered to the railway during 1830.

Subsequent designs

[edit]At around the same time, Stephenson experimented with front-mounted cylinders. The unsuccessful 0-4-0 Invicta, built in 1829 immediately after Rocket, still had them at an angle. The successful 2-2-0 locomotive Planet (1830) had internal front-mounted cylinders set to the horizontal.

Engines built to the Planet design and the subsequent 2-2-2 Patentee design of 1833 made the design of Rocket obsolete.

Replicas

[edit]

In 1923, Buster Keaton had a functioning replica built for the film Our Hospitality.[38] Two years later, the replica was used again in the Al St. John film, The Iron Mule, directed by Keaton's mentor, Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle.[39] The subsequent whereabouts of the replica are unknown. There are, however, at least two other replicas of Rocket in the US,[40] both built by Robert Stephenson and Hawthorns in 1929; one is at the Henry Ford Museum in the Metro Detroit suburb of Dearborn, Michigan,[41] the other at the Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago.[42]

The earliest full-size replica of Rocket seems to have been one depicted on a London and North Western Railway postcard (therefore pre-1923).[43][44]

A cut-away static replica was built in 1935 and displayed for many years next to the original at London's Science Museum. In 1979, a further, working replica Rocket was built by Locomotion Enterprises in the Springwell workshops at the Bowes Railway for the 150th anniversary celebrations.[45] It first worked in public on a short length of track in front of the Albert Memorial in Kensington Gardens from 25 August to 2 September 1979, before going to Newcastle on 9 September, York on 16 October[46] and running the measured mile, between Lea Green and Rainhill, on the last two days at the Rocket 150 celebrations from 24 to 26 May 1980.[47] It has a shorter chimney than the original to clear the bridge at Rainhill: successive additions of ballast and heavier rail have raised the track, leaving less headroom than in the 19th century. As of 2022, both of these replicas were based at the National Railway Museum, York, with the original Rocket.

Models

[edit]In 1963, Tri-ang Railways released a 00 Gauge model of Rocket containing three coaches and crew members. It was produced until 1969 by Tri-ang Hornby. It was re-introduced to the Hornby range in 1982 until 1983 in Hornby Railways packaging. However this 1982 re-introduced model was un-catalogued, and it was only available through exclusive retailers and from Hornby directly.[48]

In 1980, as part of the Rocket 150 anniversary, Hornby launched a 3+1⁄2 in (89 mm) gauge live steam Rocket locomotive, with additional track and coaches available separately.

In 2020, Hornby announced a newly tooled 00 Gauge model of Stephenson's Rocket with three coaches and crew members as part of their Centenary range. It was available as a standard model and a limited edition with commemorative certificate of authentication in retro 1963 Hornby Centenary Tri-ang Railways packaging.[49]

See also

[edit]- Locomotive Seguin – Seguin tubular steam locomotive (1829)

- John Bull (locomotive) – British-built railroad steam locomotive

- LMR 57 Lion – Liverpool and Manchester Railway steam locomotive

- Stourbridge Lion – Railroad steam locomotive built in 1829

- Tom Thumb (locomotive) – 1830 American-built steam locomotive

Notes

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c "Rocket" (PDF). Rainhilltrials.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Engineering Timelines – Rocket, Stephenson's locomotive".

- ^ a b Dawson, Anthony. Locomotives of the Victorian Railway: The Early Days of Steam. United Kingdom, Amberley Publishing, 2019.

- ^ Smiles, Samuel. The Story of the Life of George Stephenson: Including a Memoir of His Son Robert Stephenson. United Kingdom, John Murray, 1873.

- ^ Richard, Gibbon. Stephenson's Rocket Manual: 1829 Onwards. United Kingdom, Haynes Publishing UK, 2016.

- ^ "Stephenson's Rocket". The Science Museum Group. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ Carlson (1969), pp. 214–215, 219, 223.

- ^ "Stephenson's iconic Rocket to be displayed at Locomotion in Shildon | National Railway Museum". 2 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d Burton, Anthony (1980). The Rainhill Story. BBC. ISBN 0-563-17841-8.

- ^ Ross, David (2004). The Willing Servant. Tempus. pp. 32–33. ISBN 0-7524-2986-8.

- ^ a b Snell (1973), p. 59.

- ^ Ferneyhough (1980), p. 44.

- ^ Ferneyhough (1980), p. 46.

- ^ Ferneyhough (1980), p. 48.

- ^ Ferneyhough (1980), p. 49.

- ^ Thomas (1980), p. 66.

- ^ a b Ferneyhough (1980), p. 55.

- ^ Ferneyhough (1980), p. 56–57.

- ^ Webb, Brian; Gordon, David A. (1978). Lord Carlisle's Railways. Lichfield, Staffordshire: RCTS. p. 101. ISBN 0-901115-43-6.

- ^ Mel Draper. "Engineering and History of Robert Stephenson's Rocket". Retrieved 16 November 2010. [dead link]

- ^ The Project Gutenberg EBook of Scientific American Supplement, No. 460, 25 October 1884, by Various

- ^ Bailey, Michael R; Glithero, John P (2002). The Stephensons' Rocket. York: National Railway Museum/Science Museum. ISBN 978-1-900747-49-3.

- ^ Bailey; Glithero (2000: 35–37)

- ^ Douglas Self. "Cochrane's Rotary Steam Engines". Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ "Brampton Railway".

- ^ Liffen, John (2003). "The Patent Office Museum and the beginnings of railway locomotive preservation". In Lewis, M. J. T. (ed.). Early Railways 2. London: Newcomen Society. pp. 202–220. ISBN 0-904685-13-6.

- ^ a b Brown, Mark (23 July 2018). "'Our Elgin marbles': Stephenson's Rocket returns to north". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ^ "Stephenson's Rocket returns to Manchester for first time in 180 years". 23 May 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ Brown, Mark (8 August 2019). "'Stephenson Rocket at NRM': Stephenson's Rocket to be exhibited at National Railway Museum". NRM on Instagram. Archived from the original on 26 December 2021.

- ^ a b Snell (1973), p. 60.

- ^ Bailey, Michael R.; Glithero, John P. (2000). The Engineering and History of Rocket: A Survey Report. London: Science Museum. p. 17. ISBN 1-900-747-18-9.

- ^ Snell (1973), p. 84.

- ^ Snell (1973), pp. 55–56.

- ^ Smiles, Samuel (1862), "ch 5", The lives of the engineers, vol. 3, BoD – Books on Demand, ISBN 9783867412681

- ^ Bailey, Michael (2000), The Engineering and History of "Rocket": A Survey Report, National Railway Museum, ISBN 9781900747189

- ^ Richard, Gibbon. Stephenson's Rocket Manual: 1829 Onwards. United Kingdom, Haynes Publishing UK, 2016.

- ^ a b Snell (1973), p. 61.

- ^ Buster Keaton: Interviews, by Buster Keaton, Kevin W. Sweeney

- ^ "The Iron Mule". IMDb. 12 April 1925. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ "Surviving Steam Locomotive Search". steamlocomotive.com. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011.

- ^ "Robert Stephenson Stephensons Hawthorn Darlington Rocket". enuii.com. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ "Chicago Area Steam". steamlocomotive.com. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ "Stephenoson's Rocket 1829 Image". Archived from the original on 25 August 2011.

- ^ "Rocket" (JPG). Archived from the original on 5 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Satow, M. G. (October 1979). Slater, J.N. (ed.). "Rocket reborn". Railway Magazine. Vol. 125, no. 942. London: IPC Transport Press. pp. 472–474.

- ^ Slater, J.N., ed. (October 1979). "Notes + News". Railway Magazine. Vol. 125, no. 942. London: IPC Transport Press. p. 508.

- ^ Slater, J.N., ed. (May 1980). "Rocket 150". Railway Magazine. Vol. 126, no. 949. London: IPC Transport Press. pp. 226–227.

- ^ "Hornby Collectors Guide Rocket". Hornby Railways Collector Guide. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ "Hornby 'Stephenson's Rocket'". Hornby.com. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

References

[edit]- Carlson, Robert (1969). The Liverpool and Manchester Railway Project 1821–1831. Newton Abbot: David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4646-6. OCLC 468636235. OL 4538910W.

- Ferneyhough, Frank (1980). Liverpool & Manchester Railway 1830–1980. England: Book Club Associates. OCLC 656128257. OL 5644661W.

- Snell, J.B. (1973) [1971]. Railways: Mechanical Engineering. Arrow. ISBN 0-09-908170-9.

- Thomas, R. G. H. (1980). The Liverpool & Manchester Railway. London: B. T. Batsford. ISBN 0713405376. OCLC 6355432. OL 6395958W.

External links

[edit]- The Science Museum – Stephenson's Rocket locomotive, 1829

- The Engineer magazine examines the differences between the 1829 and 1830 Rocket, as reprinted in Scientific American Supplement, No. 460, 25 October 1884.

- Scott, Tom (28 April 2014). "The Early Steam Train With No Brakes: Stephenson's Rocket" (youtube). Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2015 – via YouTube.

- Railway locomotives introduced in 1829

- 0-2-2 locomotives

- Early steam locomotives

- English inventions

- History of Northumberland

- Individual locomotives of Great Britain

- Land speed record rail vehicles

- Liverpool and Manchester Railway locomotives

- Preserved steam locomotives of Great Britain

- Rainhill Trials locomotives

- Standard gauge steam locomotives of Great Britain

- Steam engines in the Science Museum, London