Battle of Tinchebray

| Battle of Tinchebray | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Henry I's invasion of Normandy | |||||||||

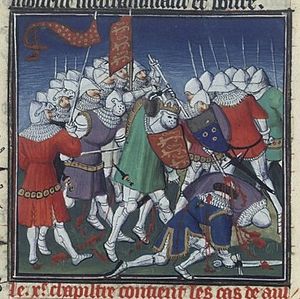

Late medieval picture from the 15th century of the Battle of Tinchebray, by the Rohan Master | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Forces of Robert Curthose, the Duke of Normandy | Forces of Henry, King of England | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Robert Curthose, Duke of Normandy (POW) William, Count of Mortain (POW) Robert of Bellême, 3rd Earl of Shrewsbury Edgar Atheling (POW) |

Henry I of England Ranulf of Bayeux Robert de Beaumont, Count of Meulan William de Warenne Elias I of Maine Alan IV, Duke of Brittany William, Count of Évreux Ralph of Tosny Robert of Montfort Robert of Grandmesnil | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Total: 6,700

|

Total: +6,700

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Captured:

Killed:

|

Henry's claim: 2 knights[2] | ||||||||

Location within Normandy | |||||||||

The Battle of Tinchebray (alternative spellings: Tinchebrai or Tenchebrai) took place on 28 September 1106, in Tinchebray (today in the Orne département of France), Normandy, between an invading force led by King Henry I of England, and the Norman army of his elder brother Robert Curthose, the Duke of Normandy.[3] Henry's knights won a decisive victory: they captured Robert, and Henry imprisoned him in England (in Devizes Castle) and then in Wales until Robert's death (in Cardiff Castle) in 1134.[4]

Prelude

[edit]Henry invaded Normandy in 1105 in the course of an ongoing dynastic dispute with his brother. He took Bayeux and Caen, but broke off his campaign because of political problems arising from an investiture controversy.[5] With these settled, he returned to Normandy in the spring of 1106.[5] After quickly taking the fortified abbey of Saint-Pierre-sur-Dives (near Falaise), Henry turned south and besieged Tinchebray Castle, on a hill above the town.[3] Tinchebray is on the border of the county of Mortain, in the southwest of Normandy, and was held by William, Count of Mortain, who was one of the few important Norman barons still loyal to Robert.[6] Duke Robert then brought up his forces to break the siege. After some unsuccessful negotiations, Duke Robert decided that a battle in the open was his best option.[6]

Battle

[edit]Henry's army was organized into three groups.[7] Ranulf of Bayeux, Robert de Beaumont, 1st Earl of Leicester, and William de Warenne, 2nd Earl of Surrey, commanded the two primary forces.[7] A reserve, commanded by Elias I of Maine, remained out of sight on the flank.[7] Alan IV, Duke of Brittany, William, Count of Évreux, Ralph of Tosny, Robert of Montfort, and Robert of Grandmesnil also fought alongside Henry. William, Count of Mortain, and Robert of Bellême, 3rd Earl of Shrewsbury, supported Robert Curthose.[8]

The battle lasted an hour.[9] Henry dismounted and ordered most of his knights to dismount. This was unusual given Norman battle tactics, and meant the infantry played a decisive role.[10] William, Count of Évreux, charged the front line, with men from Bayeux, Avranches and the Cotentin.[11] Henry's reserve proved decisive.

Aftermath

[edit]Most of Robert's army was captured or killed. Those captured included Robert, Edgar Ætheling (uncle of Henry's wife), and William, Count of Mortain.[12] Robert de Bellême, commanding the Duke's rear guard, led the retreat, saving himself from capture or death.[13] Most of the prisoners were released, but Robert Curthose and William of Mortain spent the rest of their lives in captivity.[14] Robert Curthose had a legitimate son, William Clito (1102–1128), whose claims to the duchy of Normandy led to several rebellions which continued through the rest of Henry's reign.[15]

This battle was seen by early historians as revenge for the defeat of the Anglo-Saxons at Hastings. Normandy was now conquered by the English

References

[edit]- ^ Mortinson 2022, p. 46.

- ^ Heath, Ian (2016). Armies of Feudal Europe 1066–1300 (2nd ed.). Lulu.com. p. 113. ISBN 9781326256524. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ a b C. Warren Hollister, Henry I, ed. Amanda Clark Frost (New Haven; London, Yale University Press, 2003), p. 199.

- ^ David Crouch, The Normans; The History of a Dynasty (London. New York: Hambledon Continuum, 2007), pp. 178–179.

- ^ a b David Crouch, The Normans; The History of a Dynasty (London. New York: Hambledon Continuum, 2007), pp. 176–177.

- ^ a b Charles Wendell David, Robert Curthose (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1920), p. 172.

- ^ a b c H. W. C. Davis, 'A Contemporary Account of the Battle of Tinchebrai', The English Historical Review, Vol. 24, No. 96 (Oct., 1909), p. 731.

- ^ Charles Wendell David, Robert Curthose (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1920), p. 174.

- ^ H. W. C. Davis, 'A Contemporary Account of the Battle of Tinchebrai', The English Historical Review, Vol. 24, No. 96 (Oct., 1909), p. 729.

- ^ H. W. C. Davis, 'A Contemporary Account of the Battle of Tinchebrai', The English Historical Review, Vol. 24, No. 96 (Oct., 1909), pp. 731–32.

- ^ Matthew Strickland, Anglo-Norman Warfare: Studies in Late Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman Military Organization and Warfare (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1993), p. 187.

- ^ Charles Wendell David, Robert Curthose (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1920), p. 175.

- ^ Kathleen Thompson, 'Orderic Vitalis and Robert of Bellême', Journal of Medieval History, Vol. 20 (1994), p. 137.

- ^ Charles Wendell David, Robert Curthose (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1920), p. 179.

- ^ Neveux, François; Ruelle, Claire (2006). A brief history of the Normans: the conquests that changed the face of Europe. Abho Series. Translated by Curtis, Howard. London: Robinson (published 2008). p. 177. ISBN 9781845295233.

Bibliography

[edit]- Mortinson, Jason (2022). England. Complete history of the country. Moscow: AST. ISBN 978-5-17-109889-6.