6-meter band

The 6-meter band is the lowest portion of the very high frequency (VHF) radio spectrum (50.000-54.000 MHz) internationally allocated to amateur radio use. The term refers to the average signal wavelength of 6 meters.[a]

Although located in the lower portion of the VHF band, it nonetheless occasionally displays propagation mechanisms characteristic of the high frequency (HF) bands. This normally occurs close to sunspot maximum, when solar activity increases ionization levels in the upper atmosphere. Worldwide 6 meter propagation occurred during the sunspot maximum of 2005, making 6 meter communications as good as or, in some cases and locations, better than HF frequencies. The prevalence of HF characteristics on this VHF band has inspired amateur operators to dub it the "magic band".

In the northern hemisphere, activity peaks from May through early August, when regular sporadic E propagation enables long-distance contacts spanning up to 2,500 kilometres (1,600 mi) for single-hop propagation. Multiple-hop sporadic E propagation allows intercontinental communications at distances of up to 10,000 kilometres (6,200 mi). In the southern hemisphere, sporadic E propagation is most common from November through early February.

The 6-meter band shares many characteristics with the neighboring 8-meter band, but it is somewhat higher in frequency.[a]

History

[edit]

This section needs expansion with:

|

On October 10, 1924, the 5-meter band (56–64 MHz) was first made available to amateurs in the United States by the Third National Radio Conference.[2] On October 4, 1927, the band was allocated on a worldwide basis by the International Radiotelegraph Conference in Washington, D.C. 56–60 MHz was allocated for amateur and experimental use.[3] There was no change to this allocation at the 1932 International Radiotelegraph Conference in Madrid.[4]

At the 1938 International Radiocommunication Conference in Cairo, television broadcasting was given priority in a portion of the 5- and 6-meter band in Europe. Television and low power stations, meaning those with less than 1 kW power, were allocated 56–58.5 MHz and amateurs, experimenters and low power stations were allocated 58.5–60 MHz in the European region. The conference maintained the 56–60 MHz allocation for other regions and allowed administrations in Europe latitude to allow amateurs to continue using 56–58.5 MHz.[5]

Starting in 1938, the FCC created 6 MHz wide television channel allocations working around the 5-meter amateur band with channel 2 occupying 50–56 MHz. In 1940, television channel 2 was reallocated to 60 MHz and TV channel 1 was moved to 50–56 MHz maintaining a gap for the 5-meter amateur band. When the US entered World War II, transmissions by amateur radio stations were suspended for the duration of the war. After the war, the 5-meter band was briefly reopened to amateurs from 56–60 MHz until March 1, 1946. At that time the FCC moved television channel 2 down to 54–60 MHz and reallocated channel 1 down to 44–50 MHz opening a gap that would become the Amateur radio 6-meter band in the United States.[6] FCC Order 130-C went into effect at 3 am Eastern Standard Time on March 1, 1946, and created the 6-meter band allocation for the amateur service as 50–54 MHz. Emission types A1, A2, A3 and A4 were allowed for the entire band and special emission for frequency modulation telephony was allowed from 52.5 to 54 MHz.[7][8]

At the 1947 International Radio Conference in Atlantic City, New Jersey, the amateur service was allocated 50–54 MHz in ITU Region 2 and 3. Broadcasting was allocated from 41 to 68 MHz in ITU Region 1, but allowed exclusive amateur use of the 6-meter band (50–54 MHz) in a portion of southern Africa.[9]

Amateurs in the United Kingdom remained in the 5-meter band (58.5–60 MHz) for a period of time following World War II, but lost the band to UK analogue television channel 4. They gained a 4-meter band in 1956 and eventually gained the 6 meter band from 50–52 MHz, when it was decided to terminate analogue television broadcasts on channel 2.

Amateur radio

[edit]

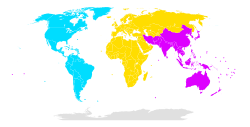

The Radio Regulations of the International Telecommunication Union allow amateur radio operations in the frequency range from 50.000–54.000 MHz in ITU Regions 2 and 3. At ITU level, Region 1 is allocated to broadcasting.[10] However, in practice a large number of ITU Region 1 countries allow amateur use of at least some of the 6 meter band.[11] Over the years portions have been vacated by VHF television broadcasting channels for one reason or another. In November 2015 the ITU World Radio Conference (WRC-15) agreed that for their next conference in 2019, Agenda Item 1.1 would study a future allocation of 50–54 MHz to amateur radio in Region 1.

Frequency allocations

[edit]

6 meter frequency allocations for amateur radio are not universal worldwide. In the United States and Canada, the band ranges from 50-54 MHz. In some other countries, the band is restricted to military communications. Further, in a few nations, the frequency range is still used for television transmissions, although most countries have (re)assigned those television channels to higher frequencies (see TV channel 1).

For many years the International Telecommunication Union did not allocate 6 meter frequencies to amateurs in Europe. However the decline of VHF television broadcasts and commercial pressure on the lower VHF spectrum enabled most European countries to provide a 6 meter amateur allocation. Eventually in 2015, following a proposal by IARU to CEPT, the ITU adopted Agenda Item AI-1.1, which four years later led to a formal ITU Region-1 allocation at WRC-19 of 50-52 MHz, with some non-European countries allocating up to 50-54MHz.

For example, the United Kingdom, has an allocation in the 6 meter band between 50 and 52 MHz, split as 50–51 MHz amateur primary, and the rest is secondary, with a lower power limit. A detailed bandplan can be obtained from the Radio Society of Great Britain (RSGB) website.[12] this has 50.0-50.5 MHz for narrowband DX modes and propagation beacons, whilst wider bandwidth FM, repeaters and Digital modes can be used in 50.5-52 MHz, including experimental Digital-ATV.

Many organizations promote regular competitions in this frequency range to promote its use and to familiarize operators to its quirks. For example, RSGB VHF Contest Committee[13] has a large number of contests on 6 meters every year.

Because of its peculiarity, there are a number of 6 meter band operator groups. These people monitor the status of the band between different paths and promote 6 meter band operations.

For a full list of countries using 6 meters, refer to the bandplan of the International Amateur Radio Union.[14]

Television interference

[edit]Because the 6 meter band is just below the frequencies formerly allocated to the old VHF television Channel 2 in North America (54–60 MHz), television interference (TVI) to neighbors' sets was a common problem for amateurs operating in this band prior to June 2009, when analog television transmissions ended in the U.S.

Equipment

[edit]

Beginning around the turn of the millennium, the availability of transceivers that include the 6 meter band has increased greatly. Many commercial HF transceivers now include the 6 meter band along with shortwave, as do a few handheld VHF/UHF transceivers. There are also a number of stand-alone 6 meter band transceivers, although commercial production of these has been relatively rare in recent years. Despite support in more available radios, however, the 6 meter band does not share the popularity of amateur radio's 2-meter band. This is due, in large part, to the larger size of 6 meter antennas, power limitations in some countries outside the United States, and the 6 meter band's greater susceptibility to local electrical interference.

As transceivers have become more available for the 6 meter band, it has quickly gained popularity. In many countries, including the United States, access is granted to entry-level license holders. Those without access to international HF frequencies often gain their first experience with truly long-distance communications on the 6 meter band. Many of these operators develop a real affection for the challenge of the band, and often continue to devote much time to it, even when they gain access to the HF frequencies after upgrading their licenses.

For antennas, horizontal polarization is used for 6 meter weak signal, SSB communications using tropospheric propagation, sporadic-E, and multi-hop sporadic-E, and for other propagation modes where polarization does not matter as much. Vertical polarization is customarily used for local FM communications, repeaters, radio control.[15]

Common uses

[edit]

- AM simplex (direct, radio-to-radio communications)

- FM simplex (direct, radio-to-radio communications)

- FM repeater operation

- Earth-Moon-Earth communication

- Sporadic E propagation

- Aurora Borealis reflection

- WSJT digital modes

- Packet radio

- SSB voice operation

- Morse code (CW) operation

- DX

- Radio control

Radio control hobby use

[edit]| Ch. | Frequency |

|---|---|

| 00 | 50.80 MHz |

| 01 | 50.82 MHz |

| 02 | 50.84 MHz |

| 03 | 50.86 MHz |

| 04 | 50.88 MHz |

| 05 | 50.90 MHz |

| 06 | 50.92 MHz |

| 07 | 50.94 MHz |

| 08 | 50.96 MHz |

| 09 | 50.98 MHz[16] (not used in Canada) |

In North America, especially in the United States[17] and Canada,[18] the 6-meter band may be used by licensed amateurs for the safe operation of radio-controlled (RC) aircraft and other types of radio control hobby miniatures. By general agreement among the amateur radio community, 200 kHz of the 6 meter band is reserved for the telecommand of models, by licensed amateurs using amateur frequencies. The sub-band reserved for this use is 50.79–50.99 MHz with ten "specified" frequencies, numbered "00" through "09", spaced at 20 kHz apart from 50.800–50.980 MHz. The upper end of the band, starting at 53.0 MHz, and going upwards in 100 kHz steps to 53.8 MHz, used to be similarly reserved for RC modelers, but with the rise of amateur repeater stations operating above 53 MHz in the United States, and very few 53 MHz RC units in Canada, the move to the lower end of the 6 meter spectrum for radio-controlled model flying activities by amateur radio operators was undertaken in North America, starting in the early 1980s, and more-or-less completed by 1991. It is still completely legal for ground-level RC model operation (cars, boats, etc.) to be accomplished on any frequency within the band, above 50.1 MHz, by any licensed amateur operator in the United States; however, an indiscriminate choice of frequencies for RC operations is discouraged by the amateur radio community via its self-imposed band plan for 6 meters.

In the United States, the Federal Communications Commission's (FCC) Part 97.215 rules regulate certain telecommand of model craft in the amateur service within the United States. It allows an unidentified maximum radiated RF power output of one watt for RC model operations of any type.[19] IF higher power is used, then all applicable sections of Part 97 must be followed.

In Canada, Industry Canada's RBR-4, Standards for the Operation of Radio Stations in the Amateur Radio Service, limits radio control of craft, for those models intended for use on any amateur radio-allocated frequency, to amateur service frequencies above 30 MHz.[20]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b The lower 8-meter band at 40 MHz is not allocated internationally (via the ITU) and only allocated to amateurs in a few countries. For details, see 8-meter band.

References

[edit]- ^ "Get Ready for the ARRL June VHF QSO Party". ARRL. 2008-06-03. Retrieved 2014-07-18.

- ^ "Frequency or wave band allocations", Recommendations for Regulation of Radio Adopted by the Third National Radio Conference (October 6–10, 1924), page 15.

- ^ International Radiotelegraph Convention of Washington, 1927 (PDF), London, UK: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 29 December 1928, p. 41, archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-08 – via International Telecommunication Union (ITU)

- ^ General Radiocommunication and Additional Regulations, Madrid 1932 (PDF). London, UK: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 1933. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-15 – via International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

- ^ General Radiocommunication Regulations and Additional Radiocommunication Regulations (Revision of Cairo, 1938) (PDF). London, UK: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 1938. p. 22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-14 – via International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

- ^ "Whatever Happened to Channel 1?". tech-notes.tv. Retrieved 2014-07-05.

- ^ Code of Federal Regulations, Title 47 – Telecommunication, Part 12 – Amateur Radio Service. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1947. Retrieved 2014-07-05.

- ^ Report of the Federal Communications Commission (PDF). 1946. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 2014-07-05.

- ^ Radio Regulations and Additional Radio Regulations (PDF). Geneva, Switzerland: General Secretariat of the International Telecommunication Union. 1949. p. 45E. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-15 – via International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

- ^ "Amateur VHF Bands". The International Amateur Radio Club (life.itu.int) 4U1ITU. Retrieved 2014-07-06.

- ^ "The 6 meter band". IARU Region 1. Retrieved 2014-07-06.

- ^ "RSGB Band Plans".

- ^ "RSGB Contest Committee". Retrieved 26 November 2023.

- ^ "IARU Regions". Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ Finley, Dave (Spring 2000). "Six Meters: An Introduction". QRPP.

- ^ "MAAC Canadian Frequency Chart". Model Aeronautics Association of Canada. MAAC. Archived from the original on November 27, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ "Frequency Chart for Model Operation". Academy of Model Aeronautics. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ "Canadian Frequency Chart". Archived from the original on 27 November 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- ^ "§97.215 – Telecommand of model craft". eCFR – Code of Federal Regulations. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- ^ "Section 5. Frequencies for Radio Control of Models". Spectrum management and telecommunications. Innovation, Science, and Economic Development Canada. RBR-4 – Standards for the Operation of Radio Stations in the Amateur Radio Service. Government of Canada. January 2014. Retrieved 2014-07-26.

Further reading

[edit]- Neubeck, Ken (October 2008). Six Meters: A guide to the magic band (4th ed.). Worldradio Books. ISBN 978-0-9705206-3-0.

External links

[edit]Propagation sites

[edit]- "Solar ham network". SolarHam.net. VE3EN.

Clubs and groups

[edit]- "United Kingdom Six Metre Group". uksmg.org.

- "Six Meter International Radio Klub". SMIRK (smirk.org).

- "SixItalia". sixitalia.org. Archived from the original on 2009-01-06.