Joan II of Navarre

| Joan II | |

|---|---|

Bust in the Louvre, originally from the Jacobin convent which housed Joan's heart | |

| Queen of Navarre | |

| Reign | 1 April 1328 – 6 October 1349 |

| Coronation | 5 March 1329 (Pamplona) |

| Predecessor | Charles I |

| Successor | Charles II |

| Co-monarch | Philip III (1328–1343) |

| Born | 28 January 1312 |

| Died | 6 October 1349 (aged 37) Navarre |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | |

| House | Capet |

| Father | Louis X of France (Louis I of Navarre) |

| Mother | Margaret of Burgundy |

Joan II (French: Jeanne; 28 January 1312[a] – 6 October 1349) was Queen of Navarre from 1328 until her death. She was the only surviving child of Louis X of France, King of France and Navarre, and Margaret of Burgundy. Joan's paternity was dubious because her mother was involved in a scandal, but Louis X declared her his legitimate daughter before he died in 1316. However, the French lords were opposed to the idea of a female monarch and elected Louis X's brother, Philip V, king. The Navarrese noblemen also paid homage to Philip. Joan's maternal grandmother, Agnes of France, and uncle, Odo IV of Burgundy, made attempts to secure the counties of Champagne and Brie (which had been the patrimony of Louis X's mother, Joan I of Navarre) to Joan, but the French royal troops defeated her supporters. After Philip V married his daughter to Odo and granted him two counties as her dowry, Odo renounced Joan's claim to Champagne and Brie in exchange for a compensation in March 1318. Joan married Philip of Évreux, who was also a member of the French royal family.

Philip V was succeeded by his brother, Charles IV, in both France and Navarre in 1322, but most Navarrese lords refused to swear loyalty to him. After Charles IV died in 1328, the Navarrese expelled the French governor and declared Joan the rightful monarch of Navarre. In France, Philip of Valois was crowned king. He concluded an agreement with Joan and her husband, who renounced Joan's claims to Champagne and Brie in exchange for three counties, while Philip acknowledged their right to Navarre. Joan and her husband were together crowned in Pamplona Cathedral on 5 March 1329.

The royal couple closely cooperated during their joint reign, but Philip of Évreux was more active. However, they mostly lived in their French domains, with Navarre being administered by governors during their absences.

Uncertain legitimacy

[edit]Joan was the daughter of Louis, King of Navarre, and his wife, Margaret of Burgundy.[2][3] Joan was born in 1312.[3] Her father was the oldest son and heir of King Philip IV of France and Queen Joan I of Navarre.[4]

Joan's mother, Margaret, and the other daughters-in-law of King Philip, Joan and Blanche of Burgundy, were arrested in 1314. They were charged with adultery with two knights, the brothers Philip and Walter of Aunay.[5] After being tortured, one of the brothers confessed that they had been the lovers of Margaret and Blanche for three years.[5] The Aunay brothers were soon executed, and Margaret and Blanche were imprisoned.[5] After the scandal, the legitimacy of Joan became dubious, because her mother was accused of having had an extramarital affair around the year of Joan's birth.[6]

Philip IV died on 26 November 1314, and Joan's father became Louis X of France.[7] Margaret technically became queen of France, but was not released and before long died in her prison in Château Gaillard.[5]

Louis stated that Joan was his legitimate daughter on his deathbed.[6] He died on 5 June 1316.[3] His second wife, Clementia of Hungary, was pregnant.[3] According to an agreement of the most powerful French lords, which was completed on 16 July, if Clementia gave birth to a son, the son was to be crowned King of France, but if a daughter was born, she and Joan could only inherit the Kingdom of Navarre and the counties of Champagne and Brie (the three realms that Louis X had inherited from his mother, Joan I of Navarre).[8] It was also agreed that Joan was to be sent to her mother's relatives in Burgundy, but her marriage could not be decided without the consent of the members of the French royal family.[8]

Orphanhood

[edit]

Clementia gave birth to a son, John the Posthumous, on 13 November 1316, but he died five days later.[9] Joan's maternal uncle, Odo IV, Duke of Burgundy, who was in Paris, entered into negotiations with Philip IV's second son, Philip the Tall, to protect Joan's interests, but Philip did not respond to Odo's demands.[8] Instead, he made arrangements for his own coronation, which took place in Reims on 9 January 1317.[9][8] The Estates-General of 1317, an assembly of the French lords strengthened Philip's position on 2 February, declaring that a woman could not inherit the French crown.[10] The Navarrese noblemen sent a delegation to Paris to swear fidelity to Philip.[11] Philip also refused to give Champagne and Brie to Joan.[12]

Joan's maternal grandmother, Agnes of France, Duchess of Burgundy, sent letters to the leading French lords, protesting against his coronation, but Philip V mounted the throne without real opposition.[9][10] Letters were also written to the lords of Champagne in Joan's name, urging them to refrain from paying homage to Philip and to protect Joan's rights to Champagne.[13] In another letter, Odo IV argued that the disinheritance of Joan by Philip V went against "the divine right of law, by custom, in the usage kept in similar cases in empires, kingdoms, fiefs, in baronies in such a length of time that there is no memory of the contrary".[13] However, Philip V's uncle, Charles of Valois, defeated Joan's supporters.[9]

Philip and Odo concluded an agreement on 27 March 1318.[9][13] Philip gave his eldest daughter (who was also named Joan) in marriage to Odo, recognizing them as heirs to the counties of Burgundy and Artois, while Joan was to marry her cousin, Philip of Évreux, with a dowry of 15,000 livres tournois in rents and the right to inherit Champagne and Brie if Philip V died leaving no sons.[13] The men also agreed that Joan was to renounce her claims to France and Navarre at the age of twelve.[14] There is no evidence that the renunciation ever took place.[15] The marriage of Joan and Philip was celebrated on 18 June 1318.[16] Thereafter Joan lived with her husband's grandmother, Marie of Brabant.[17] Although they lived near each other, Philip and Joan were not raised together due to age difference.[18] The marriage was only consummated in 1324.[19]

Extinction of the main Capet line

[edit]Philip V died without leaving a surviving son in early 1322.[16] His brother, Charles the Fair, who was Philip IV's last surviving son, succeeded him in both France and Navarre.[16] Most Navarrese refused to do homage to Charles, and he did not confirm the Fueros (or liberties) of Navarre.[20][21] Charles died on 1 February 1328, prompting another succession crisis.[16][22] Since Charles's widow, Joan of Évreux, was pregnant, the peers of France and other influential French lords assembled in Paris to elect a regent.[22] The majority of the French lords concluded that Philip of Valois had the strongest claim to the office, because he was the closest patrilinear relative of the deceased king.[23] The representatives of the Estates of the realm in Navarre, who assembled at Puente La Reina on 13 March,[24] replaced the French governor with two local lords.[25]

Charles's widow gave birth to a daughter, Blanche, on 1 April.[16][26] Her birth made it clear that the direct male line of the royal Capetian dynasty of France had become extinct with Charles the Fair's death.[16] Joan and her husband could claim the French throne, because they both were descended from French monarchs, but there were at least five other claimants, including Philip of Valois.[16] The claimants' representatives met at Saint-Germain-en-Laye to reach a compromise.[16] The general assembly of Navarre passed a resolution in May, requesting Joan to visit Navarre and to take control of its government, because the crown belonged "by right of succession and inheritance" to her.[25][24]

Philip of Valois was crowned king of France in Reims on 29 May.[26] He had no claim to Navarre, Champagne and Brie, because he was not descended from Joan I of Navarre.[27] To strengthen his position in France, in July Philip acknowledged the right of Joan and her husband to rule Navarre.[25][26] He also persuaded them to renounce Champagne and Brie in exchange for the counties of Longueville, Mortain and Angouleme, because he wanted to preserve the strategically important Champagne and Brie for the French crown.[26][28]

Accession and coronation

[edit]After the decision of the general assembly of Navarre in May 1328, Joan was regarded the lawful monarch of Navarre.[24] This decision put an end to the personal union of Navarre and France, formed through the marriage of Joan I of Navarre and Philip IV of France.[12] During the following months, Joan and her husband conducted lengthy negotiations with the Estates of the realm, especially about the role of Philip of Évreux in the administration of the kingdom.[29] Although the Navarrese had only acknowledged Joan's hereditary right to rule, her husband also claimed authority.[25] During the couple's absence, pogroms against the Jews occurred in the towns of Navarre.[30]

Joan and Philip of Évreux sent two French lords, Henri IV de Sully and Philippe de Melun, to Navarre to represent them during the negotiations.[29] The Navarrese were initially reluctant to confirm Philip's right to share the queen's rule.[31] The delegates of the general assembly first declared that Philip would be allowed to take part in the administration of Navarre in a meeting in Roncesvalles in November 1328.[32] However, they also stated that all traditional elements of the coronation (including the new monarch's elevation on a shield and the throwing of money to spectators) would only be carried out in connection with Joan.[33][32] To emphasize Philip's claim to reign in his wife's realm, Henry de Sully referred to Paul the Apostle who had stated that "the head of woman is man" in his First Epistle to the Corinthians.[32] Sully also emphasized that Joan had approved and consented to strengthen her husband's position.[32]

Joan and Philip came to Navarre in early 1329.[34] They were crowned in the Pamplona Cathedral on 5 March.[32] Both were raised on a shield and both threw money during the ceremony.[34] They signed a coronation oath, establishing their royal prerogatives.[32] The charter underlined that Joan was the "true and natural heir" of Navarre, but also declared that "all of the kingdom of Navarre would obey her consort".[35] However, the Navarrese also specified that both Joan and Philip were to renounce the crown as soon as their heir reached twenty-one, or they were obliged to pay a fine of 100,000 livres.[36] Joan also compensated her husband for his expenses connected to the acquisition of Navarre.[32]

Reign

[edit]

Joan II and Philip III of Navarre closely cooperated during their joint reign.[30] Out of the eighty-five royal decrees preserved from the period of their joint rule, forty-one documents were issued in both names.[37] However, the sources suggest that Philip was more active in several fields of government, especially legislation.[30] He signed thirty-eight decrees alone, without referring to his wife.[38] Only six documents were issued exclusively in Joan's name.[38]

After the coronation, the royal couple ordered the punishment of the perpetrators of the anti-Jewish riots and the paying of compensation to the victims.[39] The royal fortresses were repaired and a new castle was built at Castelrenault during their reign.[30] Irrigation system of the arid fields around Tudela was also constructed with the royal couple's financial support.[30] They also wanted to maintain peaceful relationship with the neighboring states.[40] They opened negotiations about the betrothal of their firstborn daughter, Joan, to Peter, the heir of Aragon, already in 1329.[41] A peace treaty with Castille was signed at Salamance on 15 March 1330.[42]

Joan and Philip left Navarre in September 1331.[34][43] Historian Elena Woodacre notes, the "royal couple had to balance the needs of their French territories alongside the rule of Navarre", which forced them to split their time between all of their domains.[43] Joan and Philip could hardly get accustomed to the "tastes and customs of the Navarrese, and were alien to their language", according to historian José María Lacarra, for which they were often absent from the kingdom.[44] During the monarchs' absence, French governors administered Navarre on their behalf.[34]

A border dispute over the ownership of the Monastery of Fitero developed into a war with Castille in 1335.[40] Peter IV of Aragon supported the Navarrese and a new peace treaty with Castille was signed on 28 February 1336.[40] Joan and Philip returned to Navarre in April 1336.[34][43] Their second visit lasted till October 1337.[34][43] Philip twice returned to the realm, but Joan did not accompany him.[43]

Philip III died in September 1343.[45] She soon replaced Philip of Melun, who had administered Navarre in the royal couple's name, with William of Brahe.[46] Before long, she also dismissed William of Brahe, replacing him with Jean de Conflans.[46] These changes may have reflected a disagreement with Philip over administration of Navarre, according to historian Elena Woodacre.[46] In 1344, a copy of the Fueros of Navarre was arranged for the queen in the local Romance language (in ydiomate Navarre), providing a spare column for its translation to the ydioma galicanum (a French variant) eventually left a blank.[44] French was probably the natural language used by Joan, even to deal with matters related with Navarre.[44] Joan established the convent of San Francisco in Olite in 1345.[30]

Joan decided to again visit Navarre, but she never returned, most probably because of the possibility of an invasion of her family's domains in France during the Hundred Years War.[45] She and her husband had supported Philip VI against Edward III of England, who claimed the French throne as the son of Joan's aunt Isabella.[47] By 1346, however, Joan was disappointed by Philip VI's failures as military leader. In November she boldly concluded a truce with the Earl of Lancaster, granting Edward's troops free passage through her county of Angoulême in return for protection of her lands.[47] She also promised not to build new fortification or allow Philip's army to use the existing ones.[47] Philip was unable to take action against her.[47]

Joan died of Black Death on 6 October 1349.[30] In her last will, she requested that her son finance a chapel in Santa Maria of Olite.[30] She was buried in the Basilica of St Denis, though her heart was buried at the now-demolished church of the Couvent des Jacobins in Paris alongside that of her husband's.[48][49]

Family

[edit]Joan's husband, Philip of Évreux, was a grandson of Philip III of France.[12] They were efficient as co-rulers but no evidence attests to the closeness of their personal relationship, in contrast to the well-documented marriages of Joan's grandparents, father and uncles. This indicates that their marriage was marked neither by particular affection nor difficulty.[50] They were very rarely apart, however, and had nine children together.[51]

- Joan (c. 1326–1387), intended as the wife of the future Peter IV of Aragon, but she became a nun at the Franciscan convent at Longchamp[52] [53]

- Maria (c. 1329 – 1347), first wife of Peter IV of Aragon[53]

- Louis (1330–1334)[53]

- Blanche (1331–1398), second wife of Philip VI of France[54]

- Charles (1332–1387), successor as count of Évreux and king of Navarre[55][56]

- Philip (c. 1333–1363), married Yolande de Dampierre[57][58]

- Agnes (1334–1396), married Gaston III, Count of Foix[59][60]

- Louis (1341–1372), Count of Beaumont-le-Roger, married firstly Maria de Lizarazu and secondly Joanna, Duchess of Durazzo[54]

- Joan (aft 1342–1403), married John I, Viscount of Rohan[57]

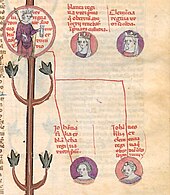

Family tree

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The Flores historiarum of Bernard Gui records the birth "V Kal Feb" in 1311 of "Ludovicus rex...filiam Johannam",[1] but modern scholarship puts her birth date in 1312.

References

[edit]- ^ Gui, Bernard (1855). "E floribus chronicorum auctore Bernardo Guidonis". In Guigniaut, Wailly (ed.). Recueil des historiens des Gaules et de la France (in Latin). Vol. XXI. Paris. p. 724.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bradbury 2007, p. 278.

- ^ a b c d Woodacre 2013, p. 51.

- ^ Woodacre 2013, pp. xix, 51.

- ^ a b c d Bradbury 2007, p. 277.

- ^ a b Woodacre 2013, p. 52.

- ^ Bradbury 2007, pp. 276, 278.

- ^ a b c d Woodacre 2013, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d e Bradbury 2007, p. 281.

- ^ a b Woodacre 2013, p. 54.

- ^ Monter 2012, p. 56.

- ^ a b c O'Callaghan 1975, p. 409.

- ^ a b c d Woodacre 2013, p. 55.

- ^ Woodacre 2013, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Woodacre 2013, p. 56.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Woodacre 2013, p. 57.

- ^ Woodacre 2013, pp. 56, 71.

- ^ Woodacre 2013, p. 197.

- ^ Woodacre 2013, p. 71.

- ^ Woodacre 2013, p. 60.

- ^ Monter 2012, p. 57.

- ^ a b Knecht 2007, p. 1.

- ^ Knecht 2007, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b c Woodacre 2013, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d Monter 2012, p. 58.

- ^ a b c d Knecht 2007, p. 2.

- ^ Woodacre 2013, p. 59.

- ^ Woodacre 2013, pp. 59–60.

- ^ a b Woodacre 2013, p. 62.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Woodacre 2013, p. 66.

- ^ Woodacre 2013, pp. 62–63.

- ^ a b c d e f g Woodacre 2013, p. 63.

- ^ Monter 2012, pp. 58–59.

- ^ a b c d e f Monter 2012, p. 59.

- ^ Woodacre 2013, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Woodacre 2013, p. 64.

- ^ Monter 2012, pp. 59–60.

- ^ a b Monter 2012, p. 60.

- ^ Woodacre 2013, pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b c Woodacre 2013, p. 69.

- ^ Woodacre 2013, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Woodacre 2013, pp. 69, 198.

- ^ a b c d e Woodacre 2013, p. 65.

- ^ a b c González Olle 1987, p. 706.

- ^ a b Woodacre 2013, p. 72.

- ^ a b c Woodacre 2013, p. 73.

- ^ a b c d Sumption 1999, p. 556.

- ^ Les Grandes Chroniques de France, vol. 9, Jules Viard, ed. (Paris: Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, 1927): 241.

- ^ Connolly, Sharon Bennett (2017). Heroines of the Medieval World. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 9781445662657.

- ^ Woodacre 2013, p. 196.

- ^ Woodacre 2013, p. 195.

- ^ Fermin Miranda Garcia, Reyes de Navarra: Felipe III y Juana II de Evreux (Pamplona, 1994).

- ^ a b c Woodacre 2013, pp. xx, 68.

- ^ a b Woodacre 2013, pp. xx, 70.

- ^ The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol.10, 722.

- ^ Woodacre 2013, pp. xx, 74.

- ^ a b Woodacre 2013, p. xx.

- ^ Tuchman 1978, p. 133.

- ^ Woodacre 2013, pp. xx, 83–84.

- ^ Tuchman 1978, p. 344.

Sources

[edit]- Bradbury, Jim (2007). The Capetians: Kings of France, 987-1328. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-85285-528-4.

- González Olle, Fernando [in Spanish] (1987). "Reconocimiento del Romance Navarro bajo Carlos II (1350)". Príncipe de Viana. 1 (182). Gobierno de Navarra; Institución Príncipe de Viana: 705–707. ISSN 0032-8472. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- Knecht, Robert (2007). The Valois: Kings of France, 1328-1589. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-85285-522-2.

- Monter, William (2012). The Rise of Female Kings in Europe, 1300-1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-17327-7.

- O'Callaghan, Joseph F. (1975). A History of Medieval Spain. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9264-5.

- Sumption, Jonathan (1999). The Hundred Years War: Trial by Battle. Vol. 1. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0851156460.

- Tuchman, Barbara W. (1978). A Distant Mirror: The Calamitious 14th Century. The Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 0-345-34957-1.

- Woodacre, Elena (2013). The Queens Regnant of Navarre: Succession, Politics, and Partnership, 1274-1512. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-33914-0.

- 1312 births

- 1349 deaths

- 14th-century deaths from plague (disease)

- 14th-century Navarrese monarchs

- 14th-century French nobility

- 14th-century queens regnant

- Burials at the Basilica of Saint-Denis

- French princesses

- Navarrese infantas

- Queens regnant of Navarre

- House of Capet

- House of Évreux

- Counts of Angoulême

- Countesses of Évreux