Joseph A. Walker

Joseph A. Walker | |

|---|---|

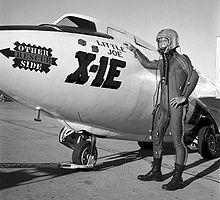

Walker in 1955 | |

| Born | Joseph Albert Walker February 20, 1921 Washington, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | June 8, 1966 (aged 45) near Barstow, California, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Washington and Jefferson College (BA, 1942) |

| Occupations | |

| Awards | |

| Space career | |

| USAF / NASA astronaut | |

| Rank | |

Time in space | 22 minutes |

| Selection | 1958 USAF Man In Space Soonest |

| Missions | X-15 Flight 35, X-15 Flight 77, X-15 Flight 90, X-15 Flight 91 |

| Retirement | August 22, 1963 |

Joseph Albert Walker (February 20, 1921 – June 8, 1966) (Capt, USAF) was an American World War II pilot, experimental physicist, NASA test pilot, and astronaut who was the first person to fly an airplane to space. He was one of twelve pilots who flew the North American X-15, an experimental spaceplane jointly operated by the Air Force and NASA.

In 1961, Walker became the first human in the mesosphere when piloting Flight 35, and in 1963, Walker made three flights above 50 miles, thereby qualifying as an astronaut according to the United States definition of the boundary of space. The latter two, X-15 Flights 90 and 91, also surpassed the Kármán line, the internationally accepted boundary of 100 kilometers (62.14 miles). Making the latter flights immediately after the completion of the Mercury and Vostok programs, Walker became the first person to fly to space twice. He was the only X-15 pilot to fly above 100 km during the program.

Walker died in a group formation accident on June 8, 1966.

Early life

[edit]Born in Washington, Pennsylvania, Walker graduated from Trinity High School in 1938. He earned his Bachelor of Arts degree in physics from Washington and Jefferson College in 1942, before entering the United States Army Air Forces. He was married and had four children.[1]

Career

[edit]Military service

[edit]During World War II, Walker flew the Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter and F-5A Lightning photo aircraft (a modified P-38) on weather reconnaissance flights. Walker earned the Distinguished Flying Cross once, awarded by General Nathan Twining in July 1944, and the Air Medal with seven oak leaf clusters.[citation needed]

Test pilot career

[edit]

with the X-1E[N 1]

After World War II, Walker separated from the Army Air Forces and joined the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio, as an experimental physicist. While in Cleveland, Walker became a test pilot, and he conducted icing research in flight, as well as in the NACA icing wind tunnel. He transferred to the High-Speed Flight Research Station in Edwards, California, in 1951.[citation needed]

Walker served for 15 years at the Edwards Flight Research Facility – now called the Neil A. Armstrong Flight Research Center. By the mid-1950s, he was a Chief Research Pilot. Walker worked on several pioneering research projects. He flew in three versions of the Bell X-1: the X-1#2 (two flights, first on August 27, 1951), X-1A (one flight), X-1E (21 flights). When Walker attempted a second flight in the X-1A on August 8, 1955, the rocket aircraft was damaged in an explosion just before being launched from the JTB-29A mothership. Walker was unhurt, though, and he climbed back into the mothership with the X-1A subsequently jettisoned.[citation needed]

Other research aircraft that he flew were the Douglas D-558-I Skystreak #3 (14 flights), Douglas D-558-II Skyrocket #2 (three flights), D-558-II #3 (two flights), Douglas X-3 Stiletto (20 flights), Northrop X-4 Bantam (two flights), and Bell X-5 (78 flights).[citation needed]

Walker was the chief project pilot for the X-3 program. Walker reportedly considered the X-3 to be the worst airplane that he ever flew. In addition to research aircraft, Walker flew many chase planes during test flights of other aircraft, and he also flew in programs that involved the North American F-100 Super Sabre, McDonnell F-101 Voodoo, Convair F-102 Delta Dagger, Lockheed F-104 Starfighter and Boeing B-47 Stratojet.[citation needed]

X-15 program

[edit]

In 1958, Walker was one of the pilots selected for the U.S. Air Force's Man In Space Soonest (MISS) project, but that project never came to fruition. That same year, NACA became the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and in 1960, Walker became the first NASA pilot to fly the X-15, and the second X-15 pilot, following Scott Crossfield, the manufacturer's test pilot. On his first X-15 flight, Walker did not realize how much power its rocket engines had, and he was crushed backward into the pilot's seat, screaming, "Oh, my God!". Then, a flight controller jokingly replied "Yes? You called?" Walker would go on to fly the X-15 25 times,[2] including the first flight of a human into the mesosphere, Flight 35, and the only two flights that exceeded 100 kilometres (62 miles) in altitude, Flight 90 (on July 19, 1963: 106 km (66 mi)) and Flight 91 (on August 22, 1963: 108 km (67 mi)).

Walker was the first American civilian to make any spaceflight,[3] and the second civilian overall, preceded only by the Soviet Union's cosmonaut, Valentina Tereshkova[4] one month earlier. Flights 90 and 91 made Walker the first human to make multiple spaceflights according to the FAI definition of greater than 100 km (62 mi).[5][6][7] Flight 77 on January 17, 1963 also qualified Walker as an astronaut, according to the US Department of Defense definition of greater than 50 mi (80 km).[8][9]

Walker flew at his highest speed in the X-15A-1: 4,104 mph (6,605 km/h) (Mach 5.92) during Flight 59 on June 27, 1962 (the fastest flight in any of the three X-15s was about 4,520 mph (7,274 km/h) (Mach 6.7) during Flight 188 flown by William J. Knight on October 3, 1967).[10]

LLRV program

[edit]Walker also became the first test pilot of the Bell Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV), which was used to develop piloting and operational techniques for lunar landings. On October 30, 1964, Walker took the LLRV on its maiden flight, reaching an altitude of about 10 ft and a total flight time of just under one minute.[11] He piloted 35 LLRV flights in total. Neil Armstrong later flew this craft many times in preparation for the spaceflight of Apollo 11 – the first human landing on the Moon – including crashing it once and barely escaping from it with his ejection seat.[12]

Death

[edit]

Walker was killed on June 8, 1966, when his F-104N Starfighter chase aircraft collided with a North American XB-70 Valkyrie.[13] At an altitude of about 25,000 ft (7.6 km)[14] Walker's Starfighter was one of five aircraft in a tight group formation for a General Electric publicity photo when his F-104 drifted into contact with the XB-70's right wingtip. The F-104 flipped over, and, rolling inverted, passed over the top of the XB-70, striking both its vertical stabilizers and its left wing in the process, and exploded, killing Walker.[N 2] The Valkyrie entered an uncontrollable spin and crashed into the ground north of Barstow, California, killing co-pilot Carl Cross. Its pilot, Alvin White, one of Walker's colleagues from the Man In Space Soonest program, ejected and was the sole survivor.

The USAF summary report of the accident investigation stated that, given the position of the F-104 relative to the XB-70, the F-104 pilot would not have been able to see the XB-70's wing, except by uncomfortably looking back over his left shoulder. The report stated that it was likely that Walker, piloting the F-104, maintained his position by looking at the fuselage of the XB-70, forward of his position.[16][17]

The F-104 was estimated to be 70 ft (20 m) to the side of, and 10 ft (3 m) below, the fuselage of the XB-70. The report concluded that from that position, without appropriate sight cues, Walker was unable to properly perceive his motion relative to the Valkyrie, leading to his aircraft drifting into contact with the XB-70's wing.[17][16]

The accident investigation also pointed to the wake vortex off the XB-70's right wingtip as the reason for the F-104's sudden roll over and into the bomber.[16] A sixth plane in the incident was a civilian Learjet 23 that held the photographer. Because the formation flight and photo were unauthorized, the careers of several Air Force colonels ended as a result of this aviation accident.[18][19][20]

Awards and honors

[edit]

Walker was a charter member and one of the first Fellows of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots. He received the Robert J. Collier Trophy, the Harmon International Trophy for Aviators, the Iven C. Kincheloe Award, the John J. Montgomery Award, and the Octave Chanute Award. His alma mater awarded him an Honorary Doctor of Aeronautical Sciences degree in 1961. He received the NASA Distinguished Service Medal in 1962. The National Pilots Association named him Pilot of the Year in 1963.[citation needed] In 1964, Walker was awarded the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[21]

Walker was inducted into the Aerospace Walk of Honor in 1991,[22] and the International Space Hall of Fame in 1995.[23] Joe Walker Middle School in Quartz Hill, California, is named in his honor as well as the Joe Walker Elementary School in Washington, Pennsylvania.[24]

On August 23, 2005, NASA officially conferred on Walker his Astronaut Wings, posthumously.[25]

Star Trek starship designer John Eaves created the Walker-class starships named for Joseph Walker that first appeared in the 2017 TV series Star Trek: Discovery, including USS Shenzhou.[26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Joseph Albert Walker Biography". astronautix.com. Archived from the original on December 28, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ^ Evans, Michelle (2013). "The X-15 Rocket Plane: Flying the First Wings Into Space-Flight Log" (PDF). Mach 25 Media. p. 11.

- ^ " Joseph A Walker." Space.com. Retrieved: September 8, 2010.

- ^ "Valentina Vladimirovna Tereshkova." Archived April 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine adm.yar.ru. Retrieved: September 8, 2010.

- ^ Evans, Michelle (2013). "The X-15 Rocket Plane: Flying the First Wings Into Space-Flight Log" (PDF). Mach 25 Media. pp. 32, 33.

- ^ "International Space Hall of Fame :: New Mexico Museum of Space History :: Inductee Profile". www.nmspacemuseum.org. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ "Captain Joseph Albert Walker". www.mccarran.com. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ Evans, Michelle (2013). "The X-15 Rocket Plane: Flying the First Wings Into Space-Flight Log" (PDF). Mach 25 Media. p. 12.

- ^ Lal, Bhavya; Nightingale, Emily (2014). "Where is Space? And Why Does That matter?". commons.erau.edu. p. 7.

- ^ Evans, Michelle (2013). "The X-15 Rocket Plane: Flying the First Wings Into Space-Flight Log" (PDF). Mach 25 Media. pp. 11, 27 & 51.

- ^ "Lunar Landing Research Vehicle". NASA Dryden Flight Research Center. Archived from the original on December 23, 2018. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

- ^ "55 Years Ago: Astronaut Armstrong Survives LLRV Crash - NASA". May 4, 2023. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ "XB-70A in collision, 2 die." Milwaukee Sentinel, June 9, 1966, p. 1-part 1.

- ^ "Inquiry begins into XB-70A collision." Milwaukee Journal, June 9, 1966, p. 12-part 1.

- ^ Yeager and Janos 1986, p. 226.

- ^ a b c Summary Report: XB-70 Accident Investigation. USAF, 1966.

- ^ a b Jenkins and Landis 2002, p. 60.

- ^ "Colonel fired for stunt role." Eugene Register-Guard, August 6, 1966. p. 4A.

- ^ "Colonel loses post over XB-70 crash." Tuscaloosa News, August 16, 1966, p. 1.

- ^ "The Crash of the XB-70." Check-Six.com. Retrieved: September 8, 2010.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ Chandler, John (September 17, 1991). "Neil Armstrong to Join Lancaster Walk of Honor". The Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. p. B3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Kentucky Astronaut to be Honored". The Courier-Journal. Louisville, Kentucky. September 11, 1995. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Joe Walker Elementary". Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- ^ Johnsen, Frederick A. "X-15 Wings." Archived June 9, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. NASA. August 23, 2005. Retrieved: September 8, 2010

- ^ TrekCore Staff (August 1, 2017). "DISCOVERY's USS Shenzhou is a 'Walker-Class' Starship". TrekCore. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Walker's X-1E was decorated with nose art of two dice and the name "Little Joe" (Little Joe being a slang term in the game of craps). Similar artwork reading "Little Joe the II" was applied to his X-15 for record-setting Flight 91. These were two rare cases of research aircraft carrying nose art.

- ^ The famous test pilot Chuck Yeager expressed his personal opinion that Walker's inexperience at formation flying was to blame, although no specific cause was ever determined in the subsequent accident investigation.[15]

Bibliography

[edit]- Coppinger, Rob. "Three new NASA astronauts, 40 years late". Flight International, June 30, 2005.

- "Joe Walker in pressure suit with X-1E." Dryden Flight Research Center Photo Archive. Retrieved: September 8, 2010.

- "Joseph (Joe) A. Walker." Dryden Flight Research Center Photo Archive. Retrieved: September 8, 2010.

- Jenkins, Dennis R. and Tony R. Landis. North American XB-70A Valkyrie WarbirdTech Volume 34. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 2002. ISBN 1-580-07056-6.

- Lefer, David. "Higher, faster, greater: X-15 test pilot who held record for altitude, speed is honored." Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, November 2, 1995, p. C1.

- Thompson, Milton O. At The Edge Of Space: The X-15 Flight Program, Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992. ISBN 1-56098-1075.

- Winter, Frank H. and F. Robert van der Linden. "Out of the Past." Aerospace America, June 1991, p. 5.

- "X-1A with pilot Joe Walker." Dryden Flight Research Center Photo Archive. Retrieved: September 8, 2010.

- Yeager, Chuck and Leo Janos. Yeager: An Autobiography. New York: Bantam, 1986. ISBN 978-0-553-25674-1.

- Jenkins, Dennis R. (2000), Hypersonics Before the Shuttle: A Concise History of the X-15 Research Airplane, NASA Technical Reports, NASA, hdl:2060/20000068530, Document ID: 20000068530

External links

[edit]- 1921 births

- 1966 deaths

- 1963 in spaceflight

- Aviators from Pennsylvania

- NASA civilian astronauts

- 20th-century American physicists

- People from Washington, Pennsylvania

- Washington & Jefferson College alumni

- United States Army Air Forces officers

- United States Army Air Forces pilots of World War II

- American test pilots

- Aviators killed in aviation accidents or incidents in the United States

- Accidental deaths in California

- Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States)

- Recipients of the Air Medal

- Collier Trophy recipients

- Harmon Trophy winners

- Flight altitude record holders

- American aviation record holders

- Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in 1966

- X-15 program

- People who have flown in suborbital spaceflight

- Military personnel from Pennsylvania