Cubism

Cubism is an early-20th-century avant-garde art movement begun in Paris that revolutionized painting and the visual arts, and influenced artistic innovations in music, ballet, literature, and architecture. Cubist subjects are analyzed, broken up, and reassembled in an abstract form—instead of depicting objects from a single perspective, the artist depicts the subject from multiple perspectives to represent the subject in a greater context.[1] Cubism has been considered the most influential art movement of the 20th century.[2][3] The term cubism is broadly associated with a variety of artworks produced in Paris (Montmartre and Montparnasse) or near Paris (Puteaux) during the 1910s and throughout the 1920s.

The movement was pioneered in partnership by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, and joined by Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Robert Delaunay, Henri Le Fauconnier, Juan Gris, and Fernand Léger.[4] One primary influence that led to Cubism was the representation of three-dimensional form in the late works of Paul Cézanne.[2] A retrospective of Cézanne's paintings was held at the Salon d'Automne of 1904, current works were displayed at the 1905 and 1906 Salon d'Automne, followed by two commemorative retrospectives after his death in 1907.[5]

In France, offshoots of Cubism developed, including Orphism, abstract art and later Purism.[6][7] The impact of Cubism was far-reaching and wide-ranging in the arts and in popular culture. Cubism introduced collage as a modern art form. In France and other countries Futurism, Suprematism, Dada, Constructivism, De Stijl and Art Deco developed in response to Cubism.[4] Early Futurist paintings hold in common with Cubism the fusing of the past and the present, the representation of different views of the subject pictured at the same time or successively, also called multiple perspective, simultaneity or multiplicity,[8] while Constructivism was influenced by Picasso's technique of constructing sculpture from separate elements.[9] Other common threads between these disparate movements include the faceting or simplification of geometric forms, and the association of mechanization and modern life.

History

[edit]Scholars have divided the history of Cubism into phases. In one scheme, the first phase of Cubism, known as Analytic Cubism, a phrase coined by Juan Gris a posteriori,[10] was both radical and influential as a short but highly significant art movement between 1910 and 1912 in France. A second phase, Synthetic Cubism, remained vital until around 1919, when the Surrealist movement gained popularity. English art historian Douglas Cooper proposed another scheme, describing three phases of Cubism in his book, The Cubist Epoch. According to Cooper there was "Early Cubism", (from 1906 to 1908) when the movement was initially developed in the studios of Picasso and Braque; the second phase being called "High Cubism", (from 1909 to 1914) during which time Juan Gris emerged as an important exponent (after 1911); and finally Cooper referred to "Late Cubism" (from 1914 to 1921) as the last phase of Cubism as a radical avant-garde movement.[11] Douglas Cooper's restrictive use of these terms to distinguish the work of Braque, Picasso, Gris (from 1911) and Léger (to a lesser extent) implied an intentional value judgement.[12]

Proto-Cubism: 1907–1908

[edit]Cubism burgeoned between 1907 and 1911. Pablo Picasso's 1907 painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon has often been considered a proto-Cubist work.

In 1908, in his review of Georges Braque's exhibition at Kahnweiler's gallery, the critic Louis Vauxcelles called Braque a daring man who despises form, "reducing everything, places and a figures and houses, to geometric schemas, to cubes".[14][15]

Vauxcelles recounted how Matisse told him at the time, "Braque has just sent in [to the 1908 Salon d'Automne] a painting made of little cubes".[15] The critic Charles Morice relayed Matisse's words and spoke of Braque's little cubes. The motif of the viaduct at l'Estaque had inspired Braque to produce three paintings marked by the simplification of form and deconstruction of perspective.[16]

Georges Braque's 1908 Houses at L’Estaque (and related works) prompted Vauxcelles, in Gil Blas, 25 March 1909, to refer to bizarreries cubiques (cubic oddities).[17] Gertrude Stein referred to landscapes made by Picasso in 1909, such as Reservoir at Horta de Ebro, as the first Cubist paintings. The first organized group exhibition by Cubists took place at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris during the spring of 1911 in a room called 'Salle 41'; it included works by Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Fernand Léger, Robert Delaunay and Henri Le Fauconnier, yet no works by Picasso or Braque were exhibited.[12]

By 1911 Picasso was recognized as the inventor of Cubism, while Braque's importance and precedence was argued later, with respect to his treatment of space, volume and mass in the L’Estaque landscapes. But "this view of Cubism is associated with a distinctly restrictive definition of which artists are properly to be called Cubists," wrote the art historian Christopher Green: "Marginalizing the contribution of the artists who exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in 1911 [...]"[12]

The assertion that the Cubist depiction of space, mass, time, and volume supports (rather than contradicts) the flatness of the canvas was made by Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler as early as 1920,[18] but it was subject to criticism in the 1950s and 1960s, especially by Clement Greenberg.[19]

Contemporary views of Cubism are complex, formed to some extent in response to the "Salle 41" Cubists, whose methods were too distinct from those of Picasso and Braque to be considered merely secondary to them. Alternative interpretations of Cubism have therefore developed. Wider views of Cubism include artists who were later associated with the "Salle 41" artists, e.g., Francis Picabia; the brothers Jacques Villon, Raymond Duchamp-Villon and Marcel Duchamp, who beginning in late 1911 formed the core of the Section d'Or (or the Puteaux Group); the sculptors Alexander Archipenko, Joseph Csaky and Ossip Zadkine as well as Jacques Lipchitz and Henri Laurens; and painters such as Louis Marcoussis, Roger de La Fresnaye, František Kupka, Diego Rivera, Léopold Survage, Auguste Herbin, André Lhote, Gino Severini (after 1916), María Blanchard (after 1916) and Georges Valmier (after 1918). More fundamentally, Christopher Green argues that Douglas Cooper's terms were "later undermined by interpretations of the work of Picasso, Braque, Gris and Léger that stress iconographic and ideological questions rather than methods of representation."[12]

John Berger identifies the essence of Cubism with the mechanical diagram. "The metaphorical model of Cubism is the diagram: The diagram being a visible symbolic representation of invisible processes, forces, structures. A diagram need not eschew certain aspects of appearance but these too will be treated as signs not as imitations or recreations."[20]

Early Cubism: 1909–1914

[edit]

There was a distinct difference between Kahnweiler's Cubists and the Salon Cubists. Prior to 1914, Picasso, Braque, Gris and Léger (to a lesser extent) gained the support of a single committed art dealer in Paris, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, who guaranteed them an annual income for the exclusive right to buy their works. Kahnweiler sold only to a small circle of connoisseurs. His support gave his artists the freedom to experiment in relative privacy. Picasso worked in Montmartre until 1912, while Braque and Gris remained there until after the First World War. Léger was based in Montparnasse.[12]

In contrast, the Salon Cubists built their reputation primarily by exhibiting regularly at the Salon d'Automne and the Salon des Indépendants, both major non-academic Salons in Paris. They were inevitably more aware of public response and the need to communicate.[12] Already in 1910 a group began to form which included Metzinger, Gleizes, Delaunay and Léger. They met regularly at Henri le Fauconnier's studio near the boulevard du Montparnasse. These soirées often included writers such as Guillaume Apollinaire and André Salmon. Together with other young artists, the group wanted to emphasise a research into form, in opposition to the Neo-Impressionist emphasis on color.[21]

Louis Vauxcelles, in his review of the 26th Salon des Indépendants (1910), made a passing and imprecise reference to Metzinger, Gleizes, Delaunay, Léger and Le Fauconnier as "ignorant geometers, reducing the human body, the site, to pallid cubes."[22][23] At the 1910 Salon d'Automne, a few months later, Metzinger exhibited his highly fractured Nu à la cheminée (Nude), which was subsequently reproduced in both Du "Cubisme" (1912) and Les Peintres Cubistes (1913).[24]

The first public controversy generated by Cubism resulted from Salon showings at the Indépendants during the spring of 1911. This showing by Metzinger, Gleizes, Delaunay, le Fauconnier and Léger brought Cubism to the attention of the general public for the first time. Amongst the Cubist works presented, Robert Delaunay exhibited his Eiffel Tower, Tour Eiffel (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York).[25]

At the Salon d'Automne of the same year, in addition to the Indépendants group of Salle 41, were exhibited works by André Lhote, Marcel Duchamp, Jacques Villon, Roger de La Fresnaye, André Dunoyer de Segonzac and František Kupka. The exhibition was reviewed in the October 8, 1911 issue of The New York Times. This article was published a year after Gelett Burgess' The Wild Men of Paris,[26] and two years prior to the Armory Show, which introduced astonished Americans, accustomed to realistic art, to the experimental styles of the European avant garde, including Fauvism, Cubism, and Futurism. The 1911 New York Times article portrayed works by Picasso, Matisse, Derain, Metzinger and others dated before 1909; not exhibited at the 1911 Salon. The article was titled The "Cubists" Dominate Paris' Fall Salon and subtitled Eccentric School of Painting Increases Its Vogue in the Current Art Exhibition – What Its Followers Attempt to Do.[27][28]

Among all the paintings on exhibition at the Paris Fall Salon none is attracting so much attention as the extraordinary productions of the so-called "Cubist" school. In fact, dispatches from Paris suggest these works are easily the main feature of the exhibition. [...]

In spite of the crazy nature of the "Cubist" theories the number of those professing them is fairly respectable. Georges Braque, André Derain, Picasso, Czobel, Othon Friesz, Herbin, Metzinger—these are a few of the names signed to canvases before which Paris has stood and now again stands in blank amazement.

What do they mean? Have those responsible for them taken leave of their senses? Is it art or madness? Who knows?[27][28]

Salon des Indépendants

[edit]The subsequent 1912 Salon des Indépendants located in Paris (20 March to 16 May 1912) was marked by the presentation of Marcel Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, which itself caused a scandal, even amongst the Cubists. It was in fact rejected by the hanging committee, which included his brothers and other Cubists. Although the work was shown in the Salon de la Section d'Or in October 1912 and the 1913 Armory Show in New York, Duchamp never forgave his brothers and former colleagues for censoring his work.[21][29] Juan Gris, a new addition to the Salon scene, exhibited his Portrait of Picasso (Art Institute of Chicago), while Metzinger's two showings included La Femme au Cheval (Woman with a horse, 1911–1912, National Gallery of Denmark).[30] Delaunay's monumental La Ville de Paris (Musée d'art moderne de la Ville de Paris) and Léger's La Noce (The Wedding, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris), were also exhibited.

Galeries Dalmau

[edit]In 1912, Galeries Dalmau presented the first declared group exhibition of Cubism worldwide (Exposició d'Art Cubista),[31][32][33] with a controversial showing by Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Juan Gris, Marie Laurencin and Marcel Duchamp (Barcelona, 20 April to 10 May 1912). The Dalmau exhibition comprised 83 works by 26 artists.[34][35][36] Jacques Nayral's association with Gleizes led him to write the Preface for the Cubist exhibition,[31] which was fully translated and reproduced in the newspaper La Veu de Catalunya.[37][38] Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 was exhibited for the first time.[39]

Extensive media coverage (in newspapers and magazines) before, during and after the exhibition launched the Galeries Dalmau as a force in the development and propagation of modernism in Europe.[39] While press coverage was extensive, it was not always positive. Articles were published in the newspapers Esquella de La Torratxa[40] and El Noticiero Universal[41] attacking the Cubists with a series of caricatures laced with derogatory text.[41] Art historian Jaime Brihuega writes of the Dalmau show: "No doubt that the exhibition produced a strong commotion in the public, who welcomed it with a lot of suspicion.[42]

A major development in Cubism occurred in 1912 with Braque's and Picasso's introduction of collage in the modernist sense. Picasso is credited with creating the first Cubist collage, Still-life With Chair Caning, in May 1912,[43] while Braque preceded Picasso in the creation of Cubist cardboard sculptures and papiers collés.[44] Papiers collés were often composed of pieces of everyday paper artifacts such as newspaper, table cloth, wallpaper and sheet music, whereas Cubist collages combined disparate materials—in the case of Still-life With Chair Caning, freely brushed oil paint and commercially printed oilcloth together on a canvas.[43]

Salon d'Automne

[edit]The Cubist contribution to the 1912 Salon d'Automne created scandal regarding the use of government owned buildings, such as the Grand Palais, to exhibit such artwork. The indignation of the politician Jean Pierre Philippe Lampué made the front page of Le Journal, 5 October 1912.[45] The controversy spread to the Municipal Council of Paris, leading to a debate in the Chambre des Députés about the use of public funds to provide the venue for such art.[46] The Cubists were defended by the Socialist deputy, Marcel Sembat.[46][47][48]

It was against this background of public anger that Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes wrote Du "Cubisme" (published by Eugène Figuière in 1912, translated to English and Russian in 1913).[49] Among the works exhibited were Le Fauconnier's vast composition Les Montagnards attaqués par des ours (Mountaineers Attacked by Bears) now at Rhode Island School of Design Museum, Joseph Csaky's Deux Femme, Two Women (a sculpture now lost), in addition to the highly abstract paintings by Kupka, Amorpha (The National Gallery, Prague), and Picabia, La Source (The Spring) (Museum of Modern Art, New York).

Abstraction and the ready-made

[edit]

The most extreme forms of Cubism were not those practiced by Picasso and Braque, who resisted total abstraction. Other Cubists, by contrast, especially František Kupka, and those considered Orphists by Apollinaire (Delaunay, Léger, Picabia and Duchamp), accepted abstraction by removing visible subject matter entirely. Kupka's two entries at the 1912 Salon d'Automne, Amorpha-Fugue à deux couleurs and Amorpha chromatique chaude, were highly abstract (or nonrepresentational) and metaphysical in orientation. Both Duchamp in 1912 and Picabia from 1912 to 1914 developed an expressive and allusive abstraction dedicated to complex emotional and sexual themes. Beginning in 1912 Delaunay painted a series of paintings entitled Simultaneous Windows, followed by a series entitled Formes Circulaires, in which he combined planar structures with bright prismatic hues; based on the optical characteristics of juxtaposed colors his departure from reality in the depiction of imagery was quasi-complete. In 1913–14 Léger produced a series entitled Contrasts of Forms, giving a similar stress to color, line and form. His Cubism, despite its abstract qualities, was associated with themes of mechanization and modern life. Apollinaire supported these early developments of abstract Cubism in Les Peintres cubistes (1913),[24] writing of a new "pure" painting in which the subject was vacated. But in spite of his use of the term Orphism these works were so different that they defy attempts to place them in a single category.[12]

Also labeled an Orphist by Apollinaire, Marcel Duchamp was responsible for another extreme development inspired by Cubism. The ready-made arose from a joint consideration that the work itself is considered an object (just as a painting), and that it uses the material detritus of the world (as collage and papier collé in the Cubist construction and Assemblage). The next logical step, for Duchamp, was to present an ordinary object as a self-sufficient work of art representing only itself. In 1913 he attached a bicycle wheel to a kitchen stool and in 1914 selected a bottle-drying rack as a sculpture in its own right.[12]

Section d'Or

[edit]

The Section d'Or, also known as Groupe de Puteaux, founded by some of the most conspicuous Cubists, was a collective of painters, sculptors and critics associated with Cubism and Orphism, active from 1911 through about 1914, coming to prominence in the wake of their controversial showing at the 1911 Salon des Indépendants. The Salon de la Section d'Or at the Galerie La Boétie in Paris, October 1912, was arguably the most important pre-World War I Cubist exhibition; exposing Cubism to a wide audience. Over 200 works were displayed, and the fact that many of the artists showed artworks representative of their development from 1909 to 1912 gave the exhibition the allure of a Cubist retrospective.[50]

The group seems to have adopted the name Section d'Or to distinguish themselves from the narrower definition of Cubism developed in parallel by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in the Montmartre quarter of Paris, and to show that Cubism, rather than being an isolated art-form, represented the continuation of a grand tradition (indeed, the golden ratio had fascinated Western intellectuals of diverse interests for at least 2,400 years).[51]

The idea of the Section d'Or originated in the course of conversations between Metzinger, Gleizes and Jacques Villon. The group's title was suggested by Villon, after reading a 1910 translation of Leonardo da Vinci's Trattato della Pittura by Joséphin Péladan.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Europeans were discovering African, Polynesian, Micronesian and Native American art. Artists such as Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso were intrigued and inspired by the stark power and simplicity of styles of those foreign cultures. Around 1906, Picasso met Matisse through Gertrude Stein, at a time when both artists had recently acquired an interest in primitivism, Iberian sculpture, African art and African tribal masks. They became friendly rivals and competed with each other throughout their careers, perhaps leading to Picasso entering a new period in his work by 1907, marked by the influence of Greek, Iberian and African art. Picasso's paintings of 1907 have been characterized as Protocubism, as notably seen in Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, the antecedent of Cubism.[13]

Art historian Douglas Cooper says Paul Gauguin and Paul Cézanne "were particularly influential to the formation of Cubism and especially important to the paintings of Picasso during 1906 and 1907".[52] Cooper goes on to say: "The Demoiselles is generally referred to as the first Cubist picture. This is an exaggeration, for although it was a major first step towards Cubism it is not yet Cubist. The disruptive, expressionist element in it is even contrary to the spirit of Cubism, which looked at the world in a detached, realistic spirit. Nevertheless, the Demoiselles is the logical picture to take as the starting point for Cubism, because it marks the birth of a new pictorial idiom, because in it Picasso violently overturned established conventions and because all that followed grew out of it."[13]

The most serious objection to regarding the Demoiselles as the origin of Cubism, with its evident influence of primitive art, is that "such deductions are unhistorical", wrote the art historian Daniel Robbins. This familiar explanation "fails to give adequate consideration to the complexities of a flourishing art that existed just before and during the period when Picasso's new painting developed."[53] Between 1905 and 1908, a conscious search for a new style caused rapid changes in art across France, Germany, The Netherlands, Italy, and Russia. The Impressionists had used a double point of view, and both Les Nabis and the Symbolists (who also admired Cézanne) flattened the picture plane, reducing their subjects to simple geometric forms. Neo-Impressionist structure and subject matter, most notably to be seen in the works of Georges Seurat (e.g., Parade de Cirque, Le Chahut and Le Cirque), was another important influence. There were also parallels in the development of literature and social thought.[53]

In addition to Seurat, the roots of cubism are to be found in the two distinct tendencies of Cézanne's later work: first his breaking of the painted surface into small multifaceted areas of paint, thereby emphasizing the plural viewpoint given by binocular vision, and second his interest in the simplification of natural forms into cylinders, spheres, and cones. However, the cubists explored this concept further than Cézanne. They represented all the surfaces of depicted objects in a single picture plane, as if the objects had all their faces visible at the same time. This new kind of depiction revolutionized the way objects could be visualized in painting and art.

The historical study of Cubism began in the late 1920s, drawing at first from sources of limited data, namely the opinions of Guillaume Apollinaire. It came to rely heavily on Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler's book Der Weg zum Kubismus (published in 1920), which centered on the developments of Picasso, Braque, Léger, and Gris. The terms "analytical" and "synthetic" which subsequently emerged have been widely accepted since the mid-1930s. Both terms are historical impositions that occurred after the facts they identify. Neither phase was designated as such at the time corresponding works were created. "If Kahnweiler considers Cubism as Picasso and Braque," wrote Daniel Robbins, "our only fault is in subjecting other Cubists' works to the rigors of that limited definition."[53]

The traditional interpretation of "Cubism", formulated post facto as a means of understanding the works of Braque and Picasso, has affected our appreciation of other twentieth-century artists. It is difficult to apply to painters such as Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Robert Delaunay and Henri Le Fauconnier, whose fundamental differences from traditional Cubism compelled Kahnweiler to question whether to call them Cubists at all. According to Daniel Robbins, "To suggest that merely because these artists developed differently or varied from the traditional pattern they deserved to be relegated to a secondary or satellite role in Cubism is a profound mistake."[53]

The history of the term "Cubism" usually stresses the fact that Matisse referred to "cubes" in connection with a painting by Braque in 1908, and that the term was published twice by the critic Louis Vauxcelles in a similar context. However, the word "cube" was used in 1906 by another critic, Louis Chassevent, with reference not to Picasso or Braque but rather to Metzinger and Delaunay:

The critical use of the word "cube" goes back at least to May 1901 when Jean Béral, reviewing the work of Henri-Edmond Cross at the Indépendants in Art et Littérature, commented that he "uses a large and square pointillism, giving the impression of mosaic. One even wonders why the artist has not used cubes of solid matter diversely colored: they would make pretty revetments." (Robert Herbert, 1968, p. 221)[55]

The term Cubism did not come into general usage until 1911, mainly with reference to Metzinger, Gleizes, Delaunay, and Léger.[53] In 1911, the poet and critic Guillaume Apollinaire accepted the term on behalf of a group of artists invited to exhibit at the Brussels Indépendants. The following year, in preparation for the Salon de la Section d'Or, Metzinger and Gleizes wrote and published Du "Cubisme"[56] in an effort to dispel the confusion raging around the word, and as a major defence of Cubism (which had caused a public scandal following the 1911 Salon des Indépendants and the 1912 Salon d'Automne in Paris).[57] Clarifying their aims as artists, this work was the first theoretical treatise on Cubism and it still remains the clearest and most intelligible. The result, not solely a collaboration between its two authors, reflected discussions by the circle of artists who met in Puteaux and Courbevoie. It mirrored the attitudes of the "artists of Passy", which included Picabia and the Duchamp brothers, to whom sections of it were read prior to publication.[12][53] The concept developed in Du "Cubisme" of observing a subject from different points in space and time simultaneously, i.e., the act of moving around an object to seize it from several successive angles fused into a single image (multiple viewpoints, mobile perspective, simultaneity or multiplicity), is a generally recognized device used by the Cubists.[58]

The 1912 manifesto Du "Cubisme" by Metzinger and Gleizes was followed in 1913 by Les Peintres Cubistes, a collection of reflections and commentaries by Guillaume Apollinaire.[24] Apollinaire had been closely involved with Picasso beginning in 1905, and Braque beginning in 1907, but gave as much attention to artists such as Metzinger, Gleizes, Delaunay, Picabia, and Duchamp.[12]

The fact that the 1912 exhibition had been curated to show the successive stages through which Cubism had transited, and that Du "Cubisme" had been published for the occasion, indicates the artists' intention of making their work comprehensible to a wide audience (art critics, art collectors, art dealers and the general public). Undoubtedly, due to the great success of the exhibition, Cubism became avant-garde movement recognized as a genre or style in art with a specific common philosophy or goal.[50]

Crystal Cubism: 1914–1918

[edit]

A significant modification of Cubism between 1914 and 1916 was signaled by a shift towards a strong emphasis on large overlapping geometric planes and flat surface activity. This grouping of styles of painting and sculpture, especially significant between 1917 and 1920, was practiced by several artists; particularly those under contract with the art dealer and collector Léonce Rosenberg. The tightening of the compositions, the clarity and sense of order reflected in these works, led to its being referred to by the critic Maurice Raynal as 'crystal' Cubism. Considerations manifested by Cubists prior to the outset of World War I—such as the fourth dimension, dynamism of modern life, the occult, and Henri Bergson's concept of duration—had now been vacated, replaced by a purely formal frame of reference.[59]

Crystal Cubism, and its associative rappel à l'ordre, has been linked with an inclination—by those who served the armed forces and by those who remained in the civilian sector—to escape the realities of the Great War, both during and directly following the conflict. The purifying of Cubism from 1914 through the mid-1920s, with its cohesive unity and voluntary constraints, has been linked to a much broader ideological transformation towards conservatism in both French society and French culture.[12]

Cubism after 1918

[edit]

The most innovative period of Cubism was before 1914.[citation needed] After World War I, with the support given by the dealer Léonce Rosenberg, Cubism returned as a central issue for artists, and continued as such until the mid-1920s when its avant-garde status was rendered questionable by the emergence of geometric abstraction and Surrealism in Paris. Many Cubists, including Picasso, Braque, Gris, Léger, Gleizes, Metzinger and Emilio Pettoruti while developing other styles, returned periodically to Cubism, even well after 1925. Cubism reemerged during the 1920s and the 1930s in the work of the American Stuart Davis and the Englishman Ben Nicholson. In France, however, Cubism experienced a decline beginning in about 1925. Léonce Rosenberg exhibited not only the artists stranded by Kahnweiler's exile but others including Laurens, Lipchitz, Metzinger, Gleizes, Csaky, Herbin and Severini. In 1918 Rosenberg presented a series of Cubist exhibitions at his Galerie de l’Effort Moderne in Paris. Attempts were made by Louis Vauxcelles to argue that Cubism was dead, but these exhibitions, along with a well-organized Cubist show at the 1920 Salon des Indépendants and a revival of the Salon de la Section d’Or in the same year, demonstrated it was still alive.[12]

The reemergence of Cubism coincided with the appearance from about 1917 to 1924 of a coherent body of theoretical writing by Pierre Reverdy, Maurice Raynal and Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler and, among the artists, by Gris, Léger and Gleizes. The occasional return to classicism—figurative work either exclusively or alongside Cubist work—experienced by many artists during this period (called Neoclassicism) has been linked to the tendency to evade the realities of the war and also to the cultural dominance of a classical or Latin image of France during and immediately following the war. Cubism after 1918 can be seen as part of a wide ideological shift towards conservatism in both French society and culture. Yet, Cubism itself remained evolutionary both within the oeuvre of individual artists, such as Gris and Metzinger, and across the work of artists as different from each other as Braque, Léger and Gleizes. Cubism as a publicly debated movement became relatively unified and open to definition. Its theoretical purity made it a gauge against which such diverse tendencies as Realism or Naturalism, Dada, Surrealism and abstraction could be compared.[12]

Influence in Asia

[edit]Japan and China were among the first countries in Asia to be influenced by Cubism. Contact first occurred via European texts translated and published in Japanese art journals in the 1910s. In the 1920s, Japanese and Chinese artists who studied in Paris, for example those enrolled at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, brought back with them both an understanding of modern art movements, including Cubism. Notable works exhibiting Cubist qualities were Tetsugorō Yorozu's Self Portrait with Red Eyes (1912) and Fang Ganmin's Melody in Autumn (1934).[61][62]

Interpretation

[edit]Intentions and criticism

[edit]

The Cubism of Picasso and Braque had more than a technical or formal significance, and the distinct attitudes and intentions of the Salon Cubists produced different kinds of Cubism, rather than a derivative of their work. "It is by no means clear, in any case," wrote Christopher Green, "to what extent these other Cubists depended on Picasso and Braque for their development of such techniques as faceting, 'passage' and multiple perspective; they could well have arrived at such practices with little knowledge of 'true' Cubism in its early stages, guided above all by their own understanding of Cézanne." The works exhibited by these Cubists at the 1911 and 1912 Salons extended beyond the conventional Cézanne-like subjects—the posed model, still-life and landscape—favored by Picasso and Braque to include large-scale modern-life subjects. Aimed at a large public, these works stressed the use of multiple perspective and complex planar faceting for expressive effect while preserving the eloquence of subjects endowed with literary and philosophical connotations.[12]

In Du "Cubisme" Metzinger and Gleizes explicitly related the sense of time to multiple perspective, giving symbolic expression to the notion of ‘duration’ proposed by the philosopher Henri Bergson according to which life is subjectively experienced as a continuum, with the past flowing into the present and the present merging into the future. The Salon Cubists used the faceted treatment of solid and space and effects of multiple viewpoints to convey a physical and psychological sense of the fluidity of consciousness, blurring the distinctions between past, present and future. One of the major theoretical innovations made by the Salon Cubists, independently of Picasso and Braque, was that of simultaneity,[12] drawing to greater or lesser extent on theories of Henri Poincaré, Ernst Mach, Charles Henry, Maurice Princet, and Henri Bergson. With simultaneity, the concept of separate spatial and temporal dimensions was comprehensively challenged. Linear perspective developed during the Renaissance was vacated. The subject matter was no longer considered from a specific point of view at a moment in time, but built following a selection of successive viewpoints, i.e., as if viewed simultaneously from numerous angles (and in multiple dimensions) with the eye free to roam from one to the other.[58]

This technique of representing simultaneity, multiple viewpoints (or relative motion) is pushed to a high degree of complexity in Metzinger's Nu à la cheminée, exhibited at the 1910 Salon d'Automne; Gleizes' monumental Le Dépiquage des Moissons (Harvest Threshing), exhibited at the 1912 Salon de la Section d'Or; Le Fauconnier's Abundance shown at the Indépendants of 1911; and Delaunay's City of Paris, exhibited at the Indépendants in 1912. These ambitious works are some of the largest paintings in the history of Cubism. Léger's The Wedding, also shown at the Salon des Indépendants in 1912, gave form to the notion of simultaneity by presenting different motifs as occurring within a single temporal frame, where responses to the past and present interpenetrate with collective force. The conjunction of such subject matter with simultaneity aligns Salon Cubism with early Futurist paintings by Umberto Boccioni, Gino Severini and Carlo Carrà; themselves made in response to early Cubism.[8]

Cubism and modern European art was introduced into the United States at the now legendary 1913 Armory Show in New York City, which then traveled to Chicago and Boston. In the Armory show Pablo Picasso exhibited La Femme au pot de moutarde (1910), the sculpture Head of a Woman (Fernande) (1909–10), Les Arbres (1907) amongst other cubist works. Jacques Villon exhibited seven important and large drypoints, while his brother Marcel Duchamp shocked the American public with his painting Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912). Francis Picabia exhibited his abstractions La Danse à la source and La Procession, Seville (both of 1912). Albert Gleizes exhibited La Femme aux phlox (1910) and L'Homme au balcon (1912), two highly stylized and faceted cubist works. Georges Braque, Fernand Léger, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Roger de La Fresnaye and Alexander Archipenko also contributed examples of their cubist works.

Cubist sculpture

[edit]Just as in painting, Cubist sculpture is rooted in Paul Cézanne's reduction of painted objects into component planes and geometric solids (cubes, spheres, cylinders, and cones). And just as in painting, it became a pervasive influence and contributed fundamentally to Constructivism and Futurism.

Cubist sculpture developed in parallel to Cubist painting. During the autumn of 1909 Picasso sculpted Head of a Woman (Fernande) with positive features depicted by negative space and vice versa. According to Douglas Cooper: "The first true Cubist sculpture was Picasso's impressive Woman's Head, modeled in 1909–10, a counterpart in three dimensions to many similar analytical and faceted heads in his paintings at the time."[11] These positive/negative reversals were ambitiously exploited by Alexander Archipenko in 1912–13, for example in Woman Walking.[12] Joseph Csaky, after Archipenko, was the first sculptor in Paris to join the Cubists, with whom he exhibited from 1911 onwards. They were followed by Raymond Duchamp-Villon and then in 1914 by Jacques Lipchitz, Henri Laurens and Ossip Zadkine.[65][66]

Indeed, Cubist construction was as influential as any pictorial Cubist innovation. It was the stimulus behind the proto-Constructivist work of both Naum Gabo and Vladimir Tatlin and thus the starting-point for the entire constructive tendency in 20th-century modernist sculpture.[12]

Architecture

[edit]

Cubism formed an important link between early-20th-century art and architecture.[67] The historical, theoretical, and socio-political relationships between avant-garde practices in painting, sculpture and architecture had early ramifications in France, Germany, the Netherlands and Czechoslovakia. Though there are many points of intersection between Cubism and architecture, only a few direct links between them can be drawn. Most often the connections are made by reference to shared formal characteristics: faceting of form, spatial ambiguity, transparency, and multiplicity.[67]

Architectural interest in Cubism centered on the dissolution and reconstitution of three-dimensional form, using simple geometric shapes, juxtaposed without the illusions of classical perspective. Diverse elements could be superimposed, made transparent or penetrate one another, while retaining their spatial relationships. Cubism had become an influential factor in the development of modern architecture from 1912 (La Maison Cubiste, by Raymond Duchamp-Villon and André Mare) onwards, developing in parallel with architects such as Peter Behrens and Walter Gropius, with the simplification of building design, the use of materials appropriate to industrial production, and the increased use of glass.[68]

Cubism was relevant to an architecture seeking a style that needed not refer to the past. Thus, what had become a revolution in both painting and sculpture was applied as part of "a profound reorientation towards a changed world".[68][69] The Cubo-Futurist ideas of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti influenced attitudes in avant-garde architecture. The influential De Stijl movement embraced the aesthetic principles of Neo-plasticism developed by Piet Mondrian under the influence of Cubism in Paris. De Stijl was also linked by Gino Severini to Cubist theory through the writings of Albert Gleizes. However, the linking of basic geometric forms with inherent beauty and ease of industrial application—which had been prefigured by Marcel Duchamp from 1914—was left to the founders of Purism, Amédée Ozenfant and Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (better known as Le Corbusier,) who exhibited paintings together in Paris and published Après le cubisme in 1918.[68] Le Corbusier's ambition had been to translate the properties of his own style of Cubism to architecture. Between 1918 and 1922, Le Corbusier concentrated his efforts on Purist theory and painting. In 1922, Le Corbusier and his cousin Jeanneret opened a studio in Paris at 35 rue de Sèvres. His theoretical studies soon advanced into many different architectural projects.[70]

La Maison Cubiste (Cubist House)

[edit]

At the 1912 Salon d'Automne an architectural installation was exhibited that quickly became known as Maison Cubiste (Cubist House), with architecture by Raymond Duchamp-Villon and interior decoration by André Mare along with a group of collaborators. Metzinger and Gleizes in Du "Cubisme", written during the assemblage of the "Maison Cubiste", wrote about the autonomous nature of art, stressing the point that decorative considerations should not govern the spirit of art. Decorative work, to them, was the "antithesis of the picture". "The true picture" wrote Metzinger and Gleizes, "bears its raison d'être within itself. It can be moved from a church to a drawing-room, from a museum to a study. Essentially independent, necessarily complete, it need not immediately satisfy the mind: on the contrary, it should lead it, little by little, towards the fictitious depths in which the coordinative light resides. It does not harmonize with this or that ensemble; it harmonizes with things in general, with the universe: it is an organism...".[71]

La Maison Cubiste was a fully furnished model house, with a facade, a staircase, wrought iron banisters, and two rooms: a living room—the Salon Bourgeois, where paintings by Marcel Duchamp, Metzinger (Woman with a Fan), Gleizes, Laurencin and Léger were hung, and a bedroom. It was an example of L'art décoratif, a home within which Cubist art could be displayed in the comfort and style of modern, bourgeois life. Spectators at the Salon d'Automne passed through the plaster facade, designed by Duchamp-Villon, to the two furnished rooms.[72] This architectural installation was subsequently exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show, New York, Chicago and Boston,[73] listed in the catalogue of the New York exhibit as Raymond Duchamp-Villon, number 609, and entitled "Facade architectural, plaster" (Façade architecturale).[74][75]

The furnishings, wallpaper, upholstery and carpets of the interior were designed by André Mare, and were early examples of the influence of cubism on what would become Art Deco. They were composed of very brightly colored roses and other floral patterns in stylized geometric forms.

Mare called the living room in which Cubist paintings were hung the Salon Bourgeois. Léger described this name as 'perfect'. In a letter to Mare prior to the exhibition Léger wrote: "Your idea is absolutely splendid for us, really splendid. People will see Cubism in its domestic setting, which is very important.[2]

"Mare's ensembles were accepted as frames for Cubist works because they allowed paintings and sculptures their independence", Christopher Green wrote, "creating a play of contrasts, hence the involvement not only of Gleizes and Metzinger themselves, but of Marie Laurencin, the Duchamp brothers (Raymond Duchamp-Villon designed the facade) and Mare's old friends Léger and Roger La Fresnaye".[76]

In 1927, Cubists Joseph Csaky, Jacques Lipchitz, Louis Marcoussis, Henri Laurens, the sculptor Gustave Miklos, and others collaborated in the decoration of a Studio House, rue Saint-James, Neuilly-sur-Seine, designed by the architect Paul Ruaud and owned by the French fashion designer Jacques Doucet, also a collector of Post-Impressionist and Cubist paintings (including Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, which he bought directly from Picasso's studio). Laurens designed the fountain, Csaky designed Doucet's staircase,[77] Lipchitz made the fireplace mantel, and Marcoussis made a Cubist rug.[78][79] [80]

Czech Cubist architecture

[edit]

The original Cubist architecture is very rare. Cubism was applied to architecture only in Bohemia (today Czech Republic) and especially in its capital, Prague.[81][82] Czech architects were the first and only ones to ever design original Cubist buildings.[83] Cubist architecture flourished for the most part between 1910 and 1914, but the Cubist or Cubism-influenced buildings were also built after World War I. After the war, the architectural style called Rondo-Cubism was developed in Prague fusing the Cubist architecture with round shapes.[84]

In their theoretical rules, the Cubist architects expressed the requirement of dynamism, which would surmount the matter and calm contained in it, through a creative idea, so that the result would evoke feelings of dynamism and expressive plasticity in the viewer. This should be achieved by shapes derived from pyramids, cubes and prisms, by arrangements and compositions of oblique surfaces, mainly triangular, sculpted facades in protruding crystal-like units, reminiscent of the so-called diamond cut, or even cavernous that are reminiscent of the late Gothic architecture. In this way, the entire surfaces of the facades including even the gables and dormers are sculpted. The grilles as well as other architectural ornaments attain a three-dimensional form. Thus, new forms of windows and doors were also created, e. g. hexagonal windows.[84] Czech Cubist architects also designed Cubist furniture.

The leading Cubist architects were Pavel Janák, Josef Gočár, Vlastislav Hofman, Emil Králíček and Josef Chochol.[84] They worked mostly in Prague but also in other Bohemian towns. The best-known Cubist building is the House of the Black Madonna in the Old Town of Prague built in 1912 by Josef Gočár with the only Cubist café in the world, Grand Café Orient.[81] Vlastislav Hofman built the entrance pavilions of Ďáblice Cemetery in 1912–1914, Josef Chochol designed several residential houses under Vyšehrad. A Cubist streetlamp has also been preserved near the Wenceslas Square, designed by Emil Králíček in 1912, who also built the Diamond House in the New Town of Prague around 1913.

Cubism in other fields

[edit]

The influence of Cubism extended to other artistic fields, outside painting and sculpture. In literature, the written works of Gertrude Stein employ repetition and repetitive phrases as building blocks in both passages and whole chapters. Most of Stein's important works utilize this technique, including the novel The Making of Americans (1906–08). Not only were they the first important patrons of Cubism, Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo were also important influences on Cubism as well. In turn, Picasso was an important influence on Stein's writing. In the field of American fiction, William Faulkner's 1930 novel As I Lay Dying can be read as an interaction with the cubist mode. The novel features narratives of the diverse experiences of 15 characters which, when taken together, produce a single cohesive body.

The poets generally associated with Cubism are Guillaume Apollinaire, Blaise Cendrars, Jean Cocteau, Max Jacob, André Salmon and Pierre Reverdy. As American poet Kenneth Rexroth explains, Cubism in poetry "is the conscious, deliberate dissociation and recombination of elements into a new artistic entity made self-sufficient by its rigorous architecture. This is quite different from the free association of the Surrealists and the combination of unconscious utterance and political nihilism of Dada."[85] Nonetheless, the Cubist poets' influence on both Cubism and the later movements of Dada and Surrealism was profound; Louis Aragon, founding member of Surrealism, said that for Breton, Soupault, Éluard and himself, Reverdy was "our immediate elder, the exemplary poet."[86] Though not as well remembered as the Cubist painters, these poets continue to influence and inspire; American poets John Ashbery and Ron Padgett have recently produced new translations of Reverdy's work. Wallace Stevens' "Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird" is also said to demonstrate how cubism's multiple perspectives can be translated into poetry.[87] Ballet’s first cubist sets and costumes were designed by Picasso in 1917 for Sergei Diaghilev’s Parade.[88] This preceded six more ballets in which Picasso "left a mark on the ballet world, influencing generations of designers and choreographers".[89] Braque followed suit with four ballets of his own commencing in 1924 Diaghliev’s Les Fâcheux.[90][91] Gris as well designed sets and costumes for Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes.[92][93] Artists such as the prolific poster designers A.M. Cassandre[94] and Edward McKnight Kauffer popularized Cubism in the fields of commercial graphic design and typography.[95] Paul Poiret and Callot Soeurs were among the couturiers that brought cubist elements—such as overlapping layers and flat planes that obscure the volumes of the body—into the world of fashion design.[96]

John Berger said: "It is almost impossible to exaggerate the importance of Cubism. It was a revolution in the visual arts as great as that which took place in the early Renaissance. Its effects on later art, on film, and on architecture are already so numerous that we hardly notice them."[97]

Gallery

[edit]-

Georges Braque, 1909–10, La guitare (Mandora, La Mandore), oil on canvas, 71.1 x 55.9 cm, Tate Modern, London

-

Albert Gleizes, 1910, La Femme aux Phlox (Woman with Phlox), oil on canvas, 81 x 100 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Exhibited in Room 41, Salon des Indépendants 1911, Armory Show 1913

-

Georges Braque, 1910, Violin and Candlestick, oil on canvas, 60.96 x 50.17 cm, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

-

Jean Metzinger, 1910–11, Deux Nus (Two Nudes, Two Women), oil on canvas, 92 x 66 cm, Gothenburg Museum of Art, Sweden. Exhibited at the first Cubist manifestation, Room 41 of the 1911 Salon des Indépendants, Paris

-

Robert Delaunay, 1910–11, La ville no. 2, oil on canvas, 146 x 114 cm, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris

-

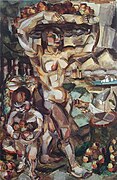

Henri Le Fauconnier, 1910–11, L'Abondance (Abundance), oil on canvas, 191 x 123 cm, Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

-

Marcel Duchamp, 1911, La sonate (Sonata), oil on canvas, 145.1 x 113.3 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art

-

Pablo Picasso, 1911, La Femme au Violon, oil on canvas, private collection, on long-term loan to Bavarian State Painting Collections, Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich

-

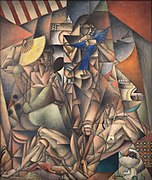

Fernand Léger, 1911–1912, Les Fumeurs (The Smokers), oil on canvas, 129.2 x 96.5 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

-

Georges Braque, 1911–12, Man with a Guitar (Figure, L’homme à la guitare), oil on canvas, 116.2 x 80.9 cm, Museum of Modern Art

-

Jacques Villon, 1912, Girl at the Piano (Fillette au piano), oil on canvas, 129.2 x 96.4 cm, oval, Museum of Modern Art, New York. Exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show

-

Francis Picabia, 1912, La Source (The Spring), oil on canvas, 249.6 x 249.3 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York

-

Fernand Léger, 1912–13, Nude Model in the Studio (Le modèle nu dans l'atelier), oil on burlap, 128.6 x 95.9 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

-

Albert Gleizes, 1912–13, Les Joueurs de football (Football Players), oil on canvas, 225.4 x 183 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

-

Jean Metzinger, 1912–1913, L'Oiseau bleu (The Blue Bird), oil on canvas, 230 x 196 cm, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants, 1913

-

Pablo Picasso, 1913–14, Femme assise dans un fauteuil (Eva), Woman in an Armchair, oil on canvas, 149.9 x 99.4 cm, Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection

-

Juan Gris, 1915, Nature morte à la nappe à carreaux (Still Life with Checked Tablecloth), oil and graphite on canvas, 116.5 x 89.2 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Leonard A. Lauder collection

-

Diego Rivera, 1915, Portrait of Ramón Gómez de la Serna, 109.6 × 90.2 cm. Latin American Art Museum of Buenos Aires

-

Jean Metzinger, April 1916, Femme au miroir (Femme à sa toilette, Lady at her Dressing Table), oil on canvas, 92.4 x 65.1 cm, private collection

-

Juan Gris, October 1916, Portrait of Josette, oil on canvas, 116 x 73 cm, Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid

-

Pablo Picasso, 1918, Arlequin au violon (Harlequin with Violin), oil on canvas, 142 x 100.3 cm, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio

-

Gino Severini, 1919, Bohémien Jouant de L'Accordéon (The Accordion Player), Museo del Novecento, Milan

-

Albert Gleizes, 1920, Femme au gant noir (Woman with Black Glove), oil on canvas, 126 x 100 cm, National Gallery of Australia

Press articles and reviews

[edit]-

Paintings by Albert Gleizes, 1910–11, Paysage, Landscape; Juan Gris (drawing); Jean Metzinger, c. 1911, Nature morte, Compotier et cruche décorée de cerfs. Published on the front page of El Correo Catalán, 25 April 1912

-

(center) Jean Metzinger, c. 1913, Le Fumeur (Man with Pipe), Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; (left) Alexander Archipenko, 1914, Danseuse du Médrano (Médrano II), (right) Archipenko, 1913, Pierrot-carrousel, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Published in Le Petit Comtois, 13 March 1914

-

Paintings by Fernand Léger, 1912, La Femme en Bleu, Woman in Blue, Kunstmuseum Basel; Jean Metzinger, 1912, Dancer in a café, Albright-Knox Art Gallery; and sculpture by Alexander Archipenko, 1912, La Vie Familiale, Family Life (destroyed). Published in Les Annales politiques et littéraires, n. 1529, 13 October 1912

-

Paintings by Gino Severini, 1911, La Danse du Pan-Pan, and Severini, 1913, L’autobus. Published in "Les Annales politiques et littéraires", Le Paradoxe Cubiste, 14 March 1920

-

Paintings by Gino Severini, 1911, Souvenirs de Voyage; Albert Gleizes, 1912, Man on a Balcony, L’Homme au balcon; Severini, 1912–13, Portrait de Mlle Jeanne Paul-Fort; Luigi Russolo, 1911–12, La Révolte. Published in "Les Annales politiques et littéraires", Le Paradoxe Cubiste (continued), n. 1916, 14 March 1920

-

Paintings by Henri Le Fauconnier, 1910–11, L'Abondance, Haags Gemeentemuseum; Jean Metzinger, 1911, Le goûter (Tea Time), Philadelphia Museum of Art; Robert Delaunay, 1910–11, La Tour Eiffel. Published in La Veu de Catalunya, 1 February 1912

-

Jean Metzinger, 1910–11, Paysage (whereabouts unknown); Gino Severini, 1911, La danseuse obsedante; Albert Gleizes, 1912, l'Homme au Balcon, Man on a Balcony (Portrait of Dr. Théo Morinaud). Published in "Les Annales politiques et littéraires", Sommaire du n. 1536, décembre 1912

-

Jean Metzinger, c. 1911, Nature morte, Compotier et cruche décorée de cerfs; Juan Gris, 1911, Study for Man in a Café; Marie Laurencin, c. 1911, Testa ab plechs; August Agero, sculpture, Bust; Juan Gris, 1912, Guitar and Glasses, or Banjo and Glasses. Published in Veu de Catalunya, 25 April 1912

-

Jean Metzinger, 1911, Le goûter (Tea Time), Philadelphia Museum of Art. Published in Le Journal, 30 September 1911

-

Paintings by Juan Gris, Bodegón; August Agero (sculpture); Jean Metzinger, 1910–11, Deux Nus, Two Nudes, Gothenburg Museum of Art; Marie Laurencin (acrylic); Albert Gleizes, 1911, Paysage, Landscape. Published in La Publicidad, 26 April 1912

-

Umberto Boccioni, 1911, La rue entre dans la maison; Luigi Russolo, 1911, Souvenir d’une nuit. Published in Les Annales politiques et littéraires, 1 December 1912

-

Francis Picabia, paintings published in the New York Tribune, 9 March 1913. Picabia held his first one-man show in New York, Exhibition of New York studies by Francis Picabia, at 291 art gallery (formerly Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession), March 17 - April 5, 1913

-

Joseph Csaky, Head, 1913, plaster lost; Robert Delaunay, Hommage à Blériot, 1914 (Kunstmuseum Basel); Henri Ottmann, The Hat Seller, published in The Sun, New York, 15 March 1914

-

Albert Gleizes, (left) in front of his painting Jazz; Jean Crotti (center) studying his Femme à la toque rouge; Marcel Duchamp (right) at his drawing board, in front of Jacques Villon's Portrait de M. J. B. peintre, The Sun, New York, 2 January 1916

-

Albert Gleizes (with Chal Post, 1915); Marcel Duchamp (with his brother Jacques Villon's Portrait de M. J. B. peintre (Jacques Bon) 1914); Jean Crotti; Hugo Robus; Stanton Macdonald-Wright; and Frances Simpson Stevens (center), Every Week, Vol. 4, No. 14, April 2, 1917, p. 14

-

Jean Metzinger, April 1916, Femme au miroir (Femme à sa toilette, Lady at her Dressing Table), The Sun, New York, Sunday 28 April 1918

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jean Metzinger, Note sur la peinture, Pan (Paris), October–November 1910

- ^ a b c "The Collection | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on August 13, 2014.

- ^ Cubism: The Leonard A. Lauder Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2014 Archived 2015-05-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "The Collection | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on June 13, 2014.

- ^ Joann Moser, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, Pre-Cubist works, 1904–1909, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press 1985, pp. 34–42

- ^ "The Collection | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art.

- ^ Magdalena Dabrowski, Geometric Abstraction, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2000

- ^ a b "The Collection | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on July 2, 2015.

- ^ "The Collection | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on October 24, 2008.

- ^ Honour, H. and J. Fleming, (2009) A World History of Art. 7th edn. London: Laurence King Publishing, p. 784. ISBN 9781856695848

- ^ a b Douglas Cooper, "The Cubist Epoch", pp. 11–221, 232, Phaidon Press Limited 1970 in association with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art ISBN 0-87587-041-4

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Christopher Green, 2009, Cubism, MoMA, Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press Archived 2014-08-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Cooper, 24

- ^ Louis Vauxcelles, Exposition Braques, Gil Blas, 14 November 1908, Gallica (BnF)

- ^ a b Danchev, Alex (March 29, 2007). Georges Braque: A Life. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 9780141905006 – via Google Books.

- ^ Futurism in Paris – The Avant-garde Explosion, Centre Pompidou, Paris 2008

- ^ Louis Vauxcelles, Le Salon des Indépendants, Gil Blas, 25 March 1909, Gallica (BnF)

- ^ D.-H. Kahnweiler. Der Weg zum Kubismus (Munich, 1920; Eng. trans., New York, 1949)

- ^ C. Greenberg. The Pasted-paper Revolution, ARTnews, 57 (1958), pp. 46–49, 60–61 (Internet Archive); repr. as 'Collage' in Art and Culture (Boston, 1961), pp. 70–83

- ^ Berger, John (1969). The Moment of Cubism. New York, NY: Pantheon. ISBN 9780297177098.

- ^ a b "Fondation Gleizes, Chronologie (in French)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 12, 2008.

- ^ "Gil Blas / dir. A. Dumont". Gallica. March 18, 1910.

- ^ Daniel Robbins, Jean Metzinger: At the Center of Cubism, 1985, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press

- ^ a b c Guillaume Apollinaire, Les Peintres cubistes: Méditations esthétiques (Paris, 1913)

- ^ "Eiffel Tower". The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation. Archived from the original on February 28, 2014.

- ^ "The Wild Men of Paris". www.architecturalrecord.com. Archived from the original on April 24, 2016.

- ^ a b "Eccentric School of Painting Increases Its Vogue in the Current Art Exhibition --- What Its Followers Attempt to Do". October 8, 1911. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ a b "The "Cubists" Dominate Paris' Fall Salon, The New York Times, October 8, 1911 (High-resolution PDF)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ "Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2)". philamuseum.org. Archived from the original on September 18, 2017.

- ^ "Statens Museum for Kunst, National Gallery of Denmark, Jean Metzinger, 1911–12, Woman with a Horse, oil on canvas, 162 × 130 cm". Archived from the original on January 15, 2012.

- ^ a b Mark Antliff and Patricia Leighten, A Cubism Reader, Documents and Criticism, 1906–1914, University of Chicago Press, 2008, pp. 293–295

- ^ Carol A. Hess, Manuel de Falla and Modernism in Spain, 1898–1936, University of Chicago Press, 2001, p. 76, ISBN 0226330389

- ^ Commemoració del centenari del cubisme a Barcelona. 1912–2012, Associació Catalana de Crítics d'Art – ACCA

- ^ Mercè Vidal, L'exposició d'Art Cubista de les Galeries Dalmau 1912, Edicions Universitat Barcelona, 1996, ISBN 8447513831

- ^ David Cottington, Cubism in the Shadow of War: The Avant-garde and Politics in Paris 1905–1914, Yale University Press, 1998, ISBN 0300075294

- ^ "Exposició d'Art Cubista". Dalmau Galleries.

- ^ Joaquim Folch i Torres, Els Cubistes a cân Dalmau, Pàgina artística de La Veu de Catalunya Archived 2018-04-22 at the Wayback Machine (Barcelona) 18 April 1912, Any 22, núm. 4637–4652 (16–30 abr. 1912)

- ^ Joaquim Folch y Torres, "El cubisme", Pàgina Artística de La Veu, La Veu de Catalunya Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, 25 April 1912 (includes numerous articles on the artists and exhibition)

- ^ a b William H. Robinson, Jordi Falgàs, Carmen Belen Lord, Barcelona and Modernity: Picasso, Gaudí, Miró, Dalí, Cleveland Museum of Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), Yale University Press, 2006, ISBN 0300121067

- ^ Cubist caricature, Esquella de La Torratxa, Núm 1740 (3 maig 1912)

- ^ a b "[Exposició d'Art Cubista – Noticiero Universal]". Dalmau Galleries.

- ^ Jaime Brihuega, Las Vanguardias Artísticas en España 1909–1936, Madrid. Istmo.1981

- ^ a b Rubin, William, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Museum of Modern Art (1989). Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism. New York, Boston: Museum of Modern Art. p. 36. ISBN 9780870706752

- ^ Rubin, William, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Museum of Modern Art (1989). Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism. New York, Boston: Museum of Modern Art. p. 30. ISBN 9780870706752

- ^ "Le Journal". Gallica. October 5, 1912. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Journal officiel de la République française. Débats parlementaires. Chambre des députés, 3 Décembre 1912, pp. 2924–2929. Bibliothèque et Archives de l'Assemblée nationale, 2012–7516 Archived 2015-09-04 at the Wayback Machine. ISSN 1270-5942

- ^ Patrick F. Barrer: Quand l'art du XXe siècle était conçu par les inconnus, pp. 93–101, gives an account of the debate.

- ^ "biography". www.peterbrooke.org.uk. Archived from the original on May 22, 2013.

- ^ "Albert-Gleizes-œuvre". September 18, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-09-18.

- ^ a b "The History and Chronology of Cubism, p. 5". Archived from the original on March 14, 2013.

- ^ "La Section d'Or, Numéro spécial, 9 Octobre 1912". Archived from the original on April 3, 2017.

- ^ Cooper, 20–27

- ^ a b c d e f g Robbins, Daniel (April 19, 1964). "Albert Gleizes, 1881–1953 : a retrospective exhibition". [New York : Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation] – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Louis Chassevent, Les Artistes Indépendants, 1906, Quelques Petits Salons. Paris, 1908. Chassevent discussed Delaunay and Metzinger in terms of Signac's influence, referring to Metzinger's "precision in the cut of his cubes..."

- ^ a b Robert Herbert, Neo-Impressionism, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, 1968

- ^ A. Gleizes and J. Metzinger. Du "Cubisme", Edition Figuière, Paris, 1912 (Eng. trans., London, 1913)

- ^ "Mercure de France : série moderne / directeur Alfred Vallette". Gallica. December 1, 1912. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Cottington, David (April 19, 2004). Cubism and Its Histories. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719050046. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Christopher Green, Cubism and Its Enemies: Modern Movements and Reaction in French Art, 1916–1928 Archived 2016-01-01 at the Wayback Machine, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1987, ISBN 0300034687

- ^ "The Museum of Modern Art". Moma.org. Retrieved 2011-06-11.

- ^ Kolokytha, Chara; Hammond, J.M.; Vlčková, Lucie. "Cubism". Routledge Encyclopedia of Modernism.

- ^ Archive, Asia Art. "Cubism in Asia: Unbounded Dialogues – Report". aaa.org.hk. Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- ^ Gris, Juan. "Portrait of Pablo Picasso". The Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- ^ Pablo Picasso, 1909–10, Head of a Woman, bronze, published in Umělecký Mĕsíčník, 1913 Archived 2014-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, Blue Mountain Project, Princeton University

- ^ Robert Rosenblum, "Cubism", Readings in Art History 2 (1976), Seuphor, Sculpture of this Century

- ^ Balas, Edith (April 19, 1998). Joseph Csáky: A Pioneer of Modern Sculpture. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 9780871692306. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Architecture and cubism. Centre canadien d'architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture : MIT Press. April 19, 2002. OCLC 915987228 – via Open WorldCat.

- ^ a b c "The Collection | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on April 5, 2012.

- ^ P. R. Banham. Theory and Design in the First Machine Age (London, 1960), p. 203

- ^ Choay, Françoise, le corbusier (1960), pp. 10–11. George Braziller, Inc. ISBN 0-8076-0104-7

- ^ "Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinge, except from Du Cubisme, 1912" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 2, 2013.

- ^ La Maison Cubiste, 1912 Archived 2013-03-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kubistische werken op de Armory Show Archived 2013-03-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Detail of Duchamp-Villon's Façade architecturale, 1913, from the Walt Kuhn Family papers and Armory Show records, 1859–1984, bulk 1900–1949". www.aaa.si.edu. Archived from the original on March 14, 2013.

- ^ "Catalogue of international exhibition of modern art: at the Armory of the Sixty-ninth Infantry". Association of American Painters and Sculptors. April 19, 1913 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Green, Christopher (January 1, 2000). Art in France, 1900–1940. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300099088. Archived from the original on November 30, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Green, Christopher (2000). Joseph Csaky's staircase in the home of Jacques Doucet. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300099088. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Rex, Aestheticus (14 April 2011). "Jacques Doucet's Studio St. James at Neuilly-sur-Seine". Aestheticusrex.blogspot.com.es. Archived from the original on 27 March 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Imbert, Dorothée (1993). The Modernist Garden in France, Dorothée Imbert, 1993, Yale University Press. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300047169. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Balas, Edith (1998). Joseph Csáky: A Pioneer of Modern Sculpture, Edith Balas, 1998, p. 5. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 9780871692306. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ a b Boněk, Jan (2014). Cubist Prague. Prague: Eminent. p. 9. ISBN 978-80-7281-469-5.

- ^ "Cubism". www.czechtourism.com. CzechTourism. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ "Cubist architecture". www.radio.cz. Radio Prague. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ a b c "Czech Cubism". www.kubista.cz. Kubista. Archived from the original on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ Rexroth, Kenneth. "The Cubist Poetry of Pierre Reverdy (Rexroth)". Bopsecrets.org. Archived from the original on 2011-05-19. Retrieved 2011-06-11.

- ^ Reverdy, Pierre. "Title Page > Pierre Reverdy: Selected Poems". Bloodaxe Books. Archived from the original on 2011-05-27. Retrieved 2011-06-11.

- ^ "Untitled Document". Archived from the original on 2007-08-13. Retrieved 2008-04-07.

- ^ Kramer, Hilton (March 24, 1973). "Picasso's Cubist Images Still Dominate 'Parade'". The New York Times. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ de Souza, Isabella. "Setting the Stage: Pablo Picasso's Foray Into Ballet". Myartbroker.com.

- ^ Unknown. "The Ballets".

- ^ Milliard, Coline (June 13, 2014). "Is Braque Finally Coming Out of Picasso's Shadow?".

- ^ "Juan Gris".

- ^ Lesso, Rosie (July 11, 2021). "Sumptuous Indulgence: Diaghilev and Juan Gris".

- ^ Heller, S., & Fili, L. (1994). Dutch Moderne: Graphic Design from De Stijl to Deco. Chronicle Books. p. 104. ISBN 0811803031.

- ^ Heller, S., & Fili, L. (1998). British Modern: Graphic Design Between the Wars. Chronicle Books. p. 18. ISBN 0811813118.

- ^ Martin, R., & Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.). (1998). Cubism and Fashion. Metropolitan Museum of Art: Distributed by H.N. Abrams. pp. 15–17, 42, 47. ISBN 9780870998881.

- ^ Berger, John. (1965). The Success and Failure of Picasso. Penguin Books, Ltd. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-679-73725-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Cubism and Abstract Art, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1936.

- Cauman, John (2001). Inheriting Cubism: The Impact of Cubism on American Art, 1909–1936. New York: Hollis Taggart Galleries. ISBN 0-9705723-4-4.

- Cooper, Douglas (1970). The Cubist Epoch. London: Phaidon in association with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art & the Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87587-041-4.

- Paolo Vincenzo Genovese, Cubismo in architettura, Mancosu Editore, Roma, 2010. In Italian.

- John Golding, Cubism: A History and an Analysis, 1907-1914, New York: Wittenborn, 1959.

- Richardson, John. A Life Of Picasso, The Cubist Rebel 1907–1916. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991. ISBN 978-0-307-26665-1

- Mark Antliff and Patricia Leighten, A Cubism Reader, Documents and Criticism, 1906–1914, The University of Chicago Press, 2008

- Christopher Green, Cubism and its Enemies, Modern Movements and Reaction in French Art, 1916–28, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1987

- Mikhail Lifshitz, The Crisis of Ugliness: From Cubism to Pop-Art. Translated and with an Introduction by David Riff. Leiden: BRILL, 2018 (originally published in Russian by Iskusstvo, 1968)

- Daniel Robbins, Sources of Cubism and Futurism, Art Journal, Vol. 41, No. 4, (Winter 1981)

- Cécile Debray, Françoise Lucbert, La Section d'or, 1912-1920-1925, Musées de Châteauroux, Musée Fabre, exhibition catalogue, Éditions Cercle d'art, Paris, 2000

- Ian Johnston, Preliminary Notes on Cubist Architecture in Prague, 2004

External links

[edit]- Cubism, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Cubist pioneer Diego Rivera

- Cubism, Agence Photographique de la Réunion des musées nationaux et du Grand Palais des Champs-Elysées (RMN)

- Czech Cubist Architecture

- Cubism, Guggenheim Collection Online

- Index of Historic Collectors and Dealers of Cubism, Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Elizabeth Carlson, Cubist Fashion: Mainstreaming Modernism after the Armory, Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 48, No. 1 (Spring 2014), pp. 1–28. doi:10.1086/675687