Hesperides

| Greek deities series |

|---|

| Nymphs |

In Greek mythology, the Hesperides (/hɛˈspɛrɪdiːz/; Ancient Greek: Ἑσπερίδες, Greek pronunciation: [hesperídes]) are the nymphs of evening and golden light of sunsets, who were the "Daughters of the Evening" or "Nymphs of the West". They were also called the Atlantides (Ancient Greek: Ἀτλαντίδες, romanized: Atlantídes) from their reputed father, Atlas.[1]

Etymology

[edit]The name means originating from Hesperos (evening). Hesperos, or Vesper in Latin, is the origin of the name Hesperus, the evening star (i.e. the planet Venus) as well as having a shared root with the English word "west".

Mythology

[edit]The nymphs of the evening

[edit]Ordinarily, the Hesperides number three, like the other Greek triads (the Three Graces and the Three Fates). "Since the Hesperides themselves are mere symbols of the gifts the apples embody, they cannot be actors in a human drama. Their abstract, interchangeable names are a symptom of their impersonality", classicist Evelyn Byrd Harrison has observed.[2]

They are sometimes portrayed as the evening daughters of Night (Nyx), either alone,[3] or with Darkness (Erebus),[4] in accord with the way Eos in the farthermost east, in Colchis, is the daughter of the titan Hyperion. The Hesperides are also listed as the daughters of Atlas[5] and Hesperis,[6] or of Phorcys and Ceto,[7] or of Zeus and Themis.[8] In a Roman literary source, the nymphs are simply said to be the daughters of Hesperus, embodiment of the "west".[9]

Nevertheless, among the names given to them, though never all at once, there were either three, four, or seven Hesperides. Apollonius of Rhodes gives the number of three with their names as Aigle, Erytheis, and Hespere (or Hespera).[10] Hyginus in his preface to the Fabulae names them as Aegle, Hesperie, and Aerica.[11][12][13][a] In another source, they are named Aegle, Arethusa, and Hesperethusa, the three daughters of Hesperus.[14][15]

Hesiod says that these "clear-voiced Hesperides",[16] daughters of Ceto and Phorcys, guarded the golden apples beyond Ocean in the far west of the world, gives the number of the Hesperides as four, and their names as: Aigle (or Aegle, "dazzling light"), Erytheia (or Erytheis), Hesperia ("sunset glow") whose name refers to the colour of the setting sun, red, yellow, or gold; and lastly Arethusa.[17] In addition, Hesperia, and Arethusa, the so-called "ox-eyed Hesperethusa".[18] Apollodorus gives the number of the Hesperides also as four, namely: Aigle, Erytheia, Hesperia (or Hesperie), and Arethusa[19] while Fulgentius named them as Aegle, Hesperie, Medusa, and Arethusa.[20][21] However, the historiographer Diodorus in his account stated that they are seven in number with no information of their names.[6] An ancient vase painting attests the following names as four: Asterope, Chrysothemis, Hygieia, and Lipara; on another seven names as Aiopis, Antheia, Donakis, Calypso, Mermesa, Nelisa, and Tara.[22] A pyxis has Hippolyte, Mapsaura, and Thetis.[23] Petrus Apianus attributed to these stars a mythical connection of their own. He believed that they were the seven Hesperides, nymph daughters of Atlas and Hesperis. Their names were: Aegle, Erythea, Arethusa, Hestia, Hespera, Hesperusa, and Hespereia.[24] A certain Crete, possible eponym of the island of Crete, was also called one of the Hesperides.[25]

They are sometimes called the "Western Maidens", the "Daughters of Evening", or Erythrai, and the "Sunset Goddesses", designations all apparently tied to their imagined location in the distant west. Hesperis is appropriately the personification of the evening (as Eos is of the dawn) and the Evening Star is Hesperus.

In addition to their tending of the garden, they have taken great pleasure in singing.[26] Euripides calls them "minstrel maids" as they possess the power of sweet song.[27] The Hesperides could be hamadryad nymphs or epimeliads as suggested by a passage in which they change into trees: "... Hespere became a poplar and Eretheis an elm, and Aegle a willow's sacred trunk ..." and in the same account, they are described figuratively or literally to have white arms and golden heads.[28]

Erytheia ("the red one") is one of the Hesperides. The name was applied to an island close to the coast of southern Hispania, which was the site of the original Punic colony of Gades (modern Cadiz). Pliny's Natural History (VI.36) records of the island of Gades:

On the side which looks towards Spain, at about 100 paces distance, is another long island, three miles wide, on which the original city of Gades stood. By Ephorus and Philistides it is called Erythia, by Timæus and Silenus Aphrodisias, and by the natives the Isle of Juno.

The island was the home of Geryon, who was overcome by Heracles.

| Variables | Item | Sources | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hesiod | Euripides | Apollonius | Cic. | Apollod. | Hyg. | Serv. | Fulg. | Apianus | Vase Paintings | |||||

| Theo. | Sch. Hipp. | Argo | Sch. | Fab. | Aen. | |||||||||

| Parents | Nyx | |||||||||||||

| Nyx and Erebus | ||||||||||||||

| Zeus and Themis | ||||||||||||||

| Phorcys and Ceto | ||||||||||||||

| Atlas and Hesperis | ||||||||||||||

| Hesperus | ||||||||||||||

| Number | 3 | |||||||||||||

| 4 | ||||||||||||||

| 7 | ||||||||||||||

| Names | Aegle | |||||||||||||

| Erythea or | ||||||||||||||

| Erytheis / Eretheis or | ||||||||||||||

| Erythia | ||||||||||||||

| Hesperia or | ||||||||||||||

| Hespere /

Hespera or |

||||||||||||||

| Hesperusa | ||||||||||||||

| Arethusa | ||||||||||||||

| Hestia | ||||||||||||||

| Medusa | ||||||||||||||

| Aerica[a] | ||||||||||||||

| Hippolyte | ||||||||||||||

| Mapsaura | ||||||||||||||

| Thetis | ||||||||||||||

| Asterope | ||||||||||||||

| Chrysothemis | ||||||||||||||

| Hygieia | ||||||||||||||

| Lipara | ||||||||||||||

| Aiopis | ||||||||||||||

| Antheia | ||||||||||||||

| Donakis | ||||||||||||||

| Calypso | ||||||||||||||

| Mermesa | ||||||||||||||

| Nelisa | ||||||||||||||

| Tara | ||||||||||||||

Land of Hesperides

[edit]

The Hesperides tend a blissful garden in a far western corner of the world, located near the Atlas mountains in North Africa at the edge of the encircling Oceanus the world ocean.[30] According to Pliny the Elder, the garden was located at Lixus, Morocco, which was also the location where Heracles fought against Antaeus.[31]

According to the Sicilian Greek poet Stesichorus, in his poem the "Song of Geryon", and the Greek geographer Strabo, in his book Geographika (volume III), the garden of the Hesperides is located in Tartessos, a location placed in the south of the Iberian peninsula.

Euesperides (in modern-day Benghazi) which was probably founded by people from Cyrene or Barca, from both of which it lies to the west, might have mythological associations with the garden of Hesperides.[32]

By Ancient Roman times, the garden of the Hesperides had lost its archaic place in religion and had dwindled to a poetic convention, in which form it was revived in Renaissance poetry, to refer both to the garden and to the nymphs that dwelt there.

The Garden of the Hesperides

[edit]

The Garden of the Hesperides is Hera's orchard in the west, where either a single apple tree or a grove grows, producing golden apples. According to the legend, when the marriage of Zeus and Hera took place, the different deities came with nuptial presents for the latter, and among them the goddess Gaia, with branches having golden apples growing on them as a wedding gift.[33] Hera, greatly admiring these, begged of Gaia to plant them in her gardens, which extended as far as Mount Atlas.

The Hesperides were given the task of tending to the grove, but occasionally picked apples from it themselves. Not trusting them, Hera also placed in the garden an immortal, never-sleeping, hundred-headed dragon named Ladon as an additional safeguard.[34] In the myth of the Judgement of Paris, it was from the Garden that Eris, Goddess of Discord, obtained the Apple of Discord, which led to the Trojan War.[35]

In later years it was thought that the "golden apples" might have actually been oranges, a fruit unknown to Europe and the Mediterranean before the Middle Ages.[36] Under this assumption, the Greek botanical name chosen for all citrus species was Hesperidoeidē (Ἑσπεριδοειδῆ, "hesperidoids") and even today the Greek word for the orange fruit is πορτοκάλι (Portokáli)--after the country of Portugal in Iberia near where the Garden of the Hesperides grew.

The Eleventh Labour of Heracles

[edit]

After Heracles completed his first ten Labours, Eurystheus gave him two more claiming that neither the Hydra counted (because Iolaus helped Heracles) nor the Augean stables (either because he received payment for the job or because the rivers did the work). The first of these two additional Labours was to steal the apples from the garden of the Hesperides. Heracles first caught the Old Man of the Sea,[37] the shape-shifting sea god, to learn where the Garden of the Hesperides was located. In some versions of the tale, Heracles went to the Caucasus, where Prometheus was confined. The Titan directed him concerning his course through the land of the peoples in the farthest north and the perils to be encountered on his homeward march after slaying Geryon in the farthest west.

Follow this straight road; and, first of all, thou shalt come to the Boreades, where do thou beware the roaring hurricane, lest unawares it twist thee up and snatch thee away in wintry whirlwind.

As payment, Heracles freed Prometheus from his daily torture.[38] This tale is more usually found in the position of the Erymanthian Boar, since it is associated with Chiron choosing to forgo immortality and taking Prometheus' place.

Another story recounts how Heracles, either at the start or at the end of his task, meets Antaeus, who was immortal as long as he touched his mother, Gaia, the earth. Heracles killed Antaeus by holding him aloft and crushing him in a bearhug.[39] Herodotus claims that Heracles stopped in Egypt, where King Busiris decided to make him the yearly sacrifice, but Heracles burst out of his chains.

Finally making his way to the Garden of the Hesperides, Heracles tricked Atlas into retrieving some of the golden apples for him, by offering to hold up the heavens for a little while (Atlas was able to take them as, in this version, he was the father or otherwise related to the Hesperides). This would have made this task – like the Hydra and Augean stables – void because he had received help. Upon his return, Atlas decided that he did not want to take the heavens back, and instead offered to deliver the apples himself, but Heracles tricked him again by agreeing to take his place on condition that Atlas relieve him temporarily so that Heracles could make his cloak more comfortable. Atlas agreed, but Heracles reneged and walked away, carrying the apples. According to an alternative version, Heracles slew Ladon instead and stole the apples.

There is another variation to the story where Heracles was the only person to steal the apples, other than Perseus, although Athena later returned the apples to their rightful place in the garden. They are considered by some to be the same "apples of joy" that tempted Atalanta, as opposed to the "apple of discord" used by Eris to start a beauty contest on Olympus (which caused "The Siege of Troy").

On Attic pottery, especially from the late fifth century, Heracles is depicted sitting in bliss in the Gardens of the Hesperides, attended by the maidens.

Argonauts' encounter

[edit]After the hero Heracles killed Ladon and stole the golden apples, the Argonauts during their journey, came to the Hesperian plain the next day. The band of heroes asked for the mercy of the Hesperides to guide them to a source of water in order to replenish their thirst. The goddesses pitying the young men, directed them to a spring created by Heracles who likewise longing for a draught while wandering the land, smote a rock near Lake Triton after which the water gushed out. The following passage recounts this meeting of the Argonauts and the nymphs:[40]

Then, like raging hounds, they [i.e. Argonauts] rushed to search for a spring; for besides their suffering and anguish, a parching thirst lay upon them, and not in vain did they wander; but they came to the sacred plain where Ladon, the serpent of the land, till yesterday kept watch over the golden apples in the garden of Atlas; and all around the nymphs, the Hesperides, were busied, chanting their lovely song. But at that time, stricken by Heracles, he lay fallen by the trunk of the apple-tree; only the tip of his tail was still writhing; but from his head down his dark spine he lay lifeless; and where the arrows had left in his blood the bitter gall of the Lernaean hydra, flies withered and died over the festering wounds. And close at hand the Hesperides, their white arms flung over their golden heads, lamented shrilly; and the heroes drew near suddenly; but the maidens, at their quick approach, at once became dust and earth where they stood. Orpheus marked the divine portent, and for his comrades addressed them in prayer: "O divine ones, fair and kind, be gracious, O queens, whether ye be numbered among the heavenly goddesses, or those beneath the earth, or be called the Solitary nymphs; come, O nymphs, sacred race of Oceanus, appear manifest to our longing eyes and show us some spring of water from the rock or some sacred flow gushing from the earth, goddesses, wherewith we may quench the thirst that burns us unceasingly. And if ever again we return in our voyaging to the Achaean land, then to you among the first of goddesses with willing hearts will we bring countless gifts, libations and banquets.

So he spake, beseeching them with plaintive voice; and they from their station near pitied their pain; and lo! First of all they caused grass to spring from the earth; and above the grass rose up tall shoots, and then flourishing saplings grew standing upright far above the earth. Hespere became a poplar and Eretheis an elm, and Aegle a willow's sacred trunk. And forth from these trees their forms looked out, as clear as they were before, a marvel exceeding great, and Aegle spake with gentle words answering their longing looks: "Surely there has come hither a mighty succour to your toils, that most accursed man, who robbed our guardian serpent of life and plucked the golden apples of the goddesses and is gone; and has left bitter grief for us. For yesterday came a man most fell in wanton violence, most grim in form; and his eyes flashed beneath his scowling brow; a ruthless wretch; and he was clad in the skin of a monstrous lion of raw hide, untanned; and he bare a sturdy bow of olive, and a bow, wherewith he shot and killed this monster here. So he too came, as one traversing the land on foot, parched with thirst; and he rushed wildly through this spot, searching for water, but nowhere was he like to see it. Now here stood a rock near the Tritonian lake; and of his own device, or by the prompting of some god, he smote it below with his foot; and the water gushed out in full flow. And he, leaning both his hands and chest upon the ground, drank a huge draught from the rifted rock, until, stooping like a beast of the field, he had satisfied his mighty maw.

Thus she spake; and they gladly with joyful steps ran to the spot where Aegle had pointed out to them the spring, until they reached it. And as when earth-burrowing ants gather in swarms round a narrow cleft, or when flies lighting upon a tiny drop of sweet honey cluster round with insatiate eagerness; so at that time, huddled together, the Minyae thronged about the spring from the rock. And thus with wet lips one cried to another in his delight: "Strange! In very truth Heracles, though far away, has saved his comrades, fordone with thirst. Would that we might find him on his way as we pass through the mainland!

Variation of the myth

[edit]According to Diodorus' account, the Hesperides did not have the golden apples. Instead they possessed flocks of sheep which excelled in beauty and were therefore called for their beauty, as the poets might do, "golden apples",[41] just as Aphroditê is called "golden" because of her loveliness. Others also say that it was because the sheep had a peculiar colour like gold that they got this designation. This version further states that Dracon ("dragon") was the name of the shepherd of the sheep, a man who excelled in strength of body and courage, who guarded the sheep and slew any who might dare to carry them off.[42]

In the Renaissance

[edit]With the revival of classical allusions in the Renaissance, the Hesperides returned to their prominent position, and the garden itself took on the name of its nymphs: Robert Greene wrote of "The fearful Dragon... that watched the garden called Hesperides".[43] Shakespeare inserted the comically insistent rhyme "is not Love a Hercules, Still climbing trees in the Hesperides" in Love's Labours Lost (iv.iii) and John Milton mentioned the "ladies of the Hesperides" in Paradise Regained (ii.357). Hesperides (published 1647) was the title of a collection of pastoral and religious verse by the Royalist poet Robert Herrick.

Gallery

[edit]-

Garden of Hesperides by Albert Herter

-

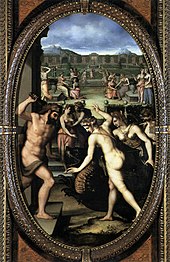

Hercules steals the Apples of the Hesperides by Lucas Cranach the Elder

-

Hercules and the Hesperides by Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini

-

Hesperides, Dance around the Golden Tree by Edward Calvert

-

Huerto de las Hespérides, 1909 by Néstor Martín-Fernández de la Torre

-

The Garden of Hesperides by Ricciardo Meacci, 1894

-

Hesperus by William Etty

-

Landschaft mit dem Garten des Hesperides by J. M. W. Turner

-

Atlas and the Hesperides by John Singer Sargent

-

Hesperides and Heracles from the book 'De malorvm avreorvm cvltvra et vsv libri quatuor' by Giovanni Baptista Ferrari

-

Hercule et les Hesperides by Rudolf Jettmar

See also

[edit]- Avalon

- Cedar Forest

- Fortunate Isles

- Garden of Eden

- Golden apple

- Immortality

- Hesperis or Hesperius

- Hesperos or Hesperus

- Hesperium

- Paradise

Footnotes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Diodorus Siculus. Library, 4.27.2

- ^ Evelyn Byrd Harrison, "Hesperides and Heroes: A Note on the Three-Figure Reliefs", Hesperia 33.1 (January 1964 pp. 76–82) pp 79–80.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 215

- ^ Hyginus. Fabulae, Preface; Cicero. De Natura Deorum, iii.44

- ^ Hyginus, De Astronomica 2.3.1 citing Pherecydes as the authority

- ^ a b Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica 4.27.2

- ^ scholia in Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica, 4.1399

- ^ scholia in Euripides, Hippolytus, 742

- ^ Servius, ad Aeneid, iv.484.

- ^ Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 4.1396–1449

- ^ Wilhelm Friedrich Rinck (1853). Die Religion der Hellenen: aus den Mythen, den Lehren der Philosophen und dem Kultus. p. 352 [1]

- ^ Higí (2011). Faules (vol. I) (in Catalan). Fundació Bernat Metge. ISBN 9788498591811.

- ^ Hyginus. Fabulae, Preface.

- ^ Peter Parley (1839). Tales about the mythology of Greece and Rome, p. 356

- ^ Charles N. Baldwin, Henry Howland Crapo (1825). A Universal Biographical Dictionary, p. 414

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 275

- ^ Servius, Commentary on Virgil's Aeneid 4.484 quoting Hesiod

- ^ Hesiod, Homeric Hymns and Homerica, edited and translated by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. [2]

- ^ Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 2.5.11

- ^ Fulgentius, Expositio Virgilianae continentiae secundum philosophos moralis[full citation needed]

- ^ Ersch, Johann Samuel (1830). Allgemeine encyclopädie der wissenschaften und künste in alphabetischer folge von genannten schrifts bearbeitet und herausgegeben von J. S. Ersch und J. G. Gruber. p. 148 [3]

- ^ Walters, Henry Beauchamp (1905). History of Ancient Pottery: Greek, Etruscan, and Roman: Based on the Work of Samuel Birch. Vol. 2. p. 92.

- ^ Attic pyxis (red-figure) by Douris, circa 470. London, British Museum: E. 772.

- ^ Michael Grant, John Hazel (2002). Who's who in Classical Mythology, p. 268 [4]

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium s.v. Krētē; Solinus, Polyhistor, 11.5. Translated by Arwen Apps

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony, 518; Orphic Fragments, 17; Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica, 4.1399.

- ^ Euripides, Heracles, 394

- ^ Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica, 4.1422ff

- ^ "Circular Pyxis". The Walters Art Museum.

- ^ A confusion of the Garden of the Hesperides with an equally idyllic Arcadia is a modern one, conflating Sir Philip Sidney's Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia and Robert Herrick's Hesperides: both are viewed by Renaissance poets as oases of bliss, but they were not connected by the Greeks. The development of Arcadia as an imagined setting for pastoral is the contribution of Theocritus to Hellenistic culture: see Arcadia (utopia).

- ^ Pliny the Elder. Historia Naturalis - Book V. Translated by H. Rackham. Harvard University Press. pp. 220–221.

- ^ Ham, Anthony, Libya, 2002, p.156

- ^ Poet. Astron. ii. 3

- ^ quoting Pherecydes, Hyginus. Astronomica ii.3

- ^ Colluthus. Rape of Helen, 59ff. Translated by Mair, A. W. Loeb Classical Library Volume 219. London: William Heinemann Ltd, 1928

- ^ Athenaeus. Deipnosophistae, 3.83c

- ^ Karl Kerenyi, The Heroes of the Greeks, 1959, p.172, identifies him in this context as Nereus; as a shape-shifter he is often identified as Proteus.

- ^ Aeschylus. Prometheus Unbound, Fragment 109 (from Galen, Commentary on Hippocrates' Epidemics, 6.17.1). Translated by Weir Smyth.

- ^ Apollodorus ii. 5; Hyginus, Fab. 31

- ^ Apollonius of Rhodes. Argonautica, 4.1393ff.

- ^ The word μῆλον means both "sheep" and "apple"

- ^ Diodorus Siculus. Library, 4.26.2-3

- ^ R. Greene, Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay (published 1594)

General references

[edit]- Grimal, Pierre, The Dictionary of Classical Mythology, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996, ISBN 978-0-631-20102-1. "Hesperides" p. 213

- Smith, William (1873). "Hespe'rides". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London.