Grande Ronde River

| Grande Ronde River | |

|---|---|

The Grande Ronde River just above Wildcat Creek, near Troy, Oregon | |

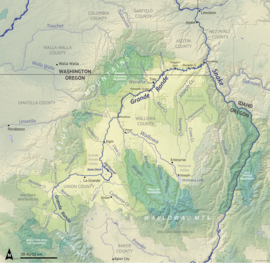

Map of the Grande Ronde River watershed | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oregon, Washington |

| Counties | Union and Wallowa counties in Oregon, Asotin County in Washington |

| Cities | La Grande, Elgin |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Blue Mountains |

| • location | Anthony Lakes, Union County, Oregon |

| • coordinates | 44°57′34″N 118°15′38″W / 44.95944°N 118.26056°W[1] |

| • elevation | 7,460 ft (2,270 m)[2] |

| Mouth | Snake River |

• location | Rogersburg, Asotin County, Washington |

• coordinates | 46°4′49″N 116°58′47″W / 46.08028°N 116.97972°W[1] |

• elevation | 820 ft (250 m)[1] |

| Length | 210 mi (340 km)[3] |

| Basin size | 4,105 sq mi (10,630 km2)[3] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | near Troy, OR, about 45.3 mi (72.9 km) from the mouth[4] |

| • average | 3,016 cu ft/s (85.4 m3/s) |

| • minimum | 344 cu ft/s (9.7 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 51,800 cu ft/s (1,470 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Wenaha River |

| • right | Catherine Creek, Wallowa River, Joseph Creek |

| Type | Wild, Recreational |

| Designated | October 28, 1988 |

The Grande Ronde River (/ɡrænd rɑːnd/ or, less commonly, /ɡrænd raʊnd/) is a 210-mile (340 km) long[3] tributary of the Snake River, flowing through northeast Oregon and southeast Washington in the United States. Its watershed is situated in the eastern Columbia Plateau, bounded by the Blue Mountains and Wallowa Mountains to the west of Hells Canyon. The river flows generally northeast from its forested headwaters west of La Grande, Oregon, through the agricultural Grande Ronde Valley in its middle course, and through rugged canyons cut from ancient basalt lava flows in its lower course. While it joins the Snake River upstream of Asotin, Washington, more than 90 percent of the river's watershed is in Oregon.

The river was used for centuries by multiple Native American tribes, who fished, gathered and hunted across much of the watershed and convened in the Grande Ronde Valley for trade. European exploration began with the fur trade in the early 1800s; later, the Grande Ronde Valley provided a key resting point along the Oregon Trail. By the 1850s, the wave of settlement had spread to northeast Oregon, and the river was the scene of several conflicts, including the 1856 Grande Ronde massacre. Nearby gold discoveries drove emerging farming and logging industries in the Grande Ronde region, and by the 1880s most indigenous peoples had been forced away from the area and onto reservations, though several tribes maintain subsistence fishing rights along the river.

While the Grande Ronde and Wallowa Valleys developed into productive farming areas, further efforts to regulate and dam the river in the 20th century proved unsuccessful. Due to its free-flowing nature, the river provides a significant amount of spawning habitat for anadromous fish (salmon and steelhead) in the Columbia River system. These populations have declined due to the building of dams downstream on the Columbia and Snake Rivers, as well as habitat degradation in the Grande Ronde watershed. Despite efforts to protect and restore aquatic habitat, anadromous fish populations in the 21st century remain much lower than historical levels.

About 44 miles (71 km) of the Grande Ronde in Oregon are federally protected as a National Wild and Scenic River, in addition to parts of several tributaries including the Wallowa and Wenaha Rivers. Much of the Wild and Scenic section in Oregon, as well as the lowermost stretches of the river in Washington, can only be reached by water. The river's undeveloped surroundings and abundant wildlife make it a popular location for sport fishing, hunting, wildlife viewing, and boating.

Course

[edit]The Grande Ronde's source is an alpine meadow in southern Union County, Oregon, west of Anthony Lakes and the Anthony Lakes Ski Area, about 7,460 feet (2,270 m) above sea level.[2][5] The headwaters are in the Elkhorn Mountains, a sub-range of the Blue Mountains.[6] The river initially flows north through the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest, turning east where Meadow Creek joins it from the left near Camp Elkanah.[7] It then flows through Red Bridge and Hilgard Junction state parks, passing through a narrow canyon before entering the Grande Ronde Valley at the city of La Grande.[8][9]

The Grande Ronde Valley, measuring about 35 miles (56 km) from north to south and up to 15 miles (24 km) from east to west, consists mostly of irrigated farmland and also includes the communities of Union, Cove, Imbler and Summerville.[6] The river once flowed in a large U-shaped bend through the east side of the valley, but is now artificially diverted to the north via the State Ditch, bypassing the long meandering section to the east.[10]: 52 At the end of the ditch the original channel – which now carries water from Catherine Creek– rejoins from the right.[9][10]: 52 At the northern end of the valley, the Grande Ronde flows through Rhinehart Gap into the smaller Indian Valley and the city of Elgin, where it receives Clark Creek from the right and Phillips Creek from the left.[11][12]

Below Elgin, the Grande Ronde enters a series of deep, winding canyons for the remaining 95 miles (153 km) of its course to the Snake River. It receives Lookingglass Creek from the left then crosses into Wallowa County at Rondowa, where it is joined from the right by its largest tributary, the Wallowa River.[13] Entering the Umatilla National Forest, it turns east, receiving Bear and Elbow Creeks from the left and Wildcat, Mud and Courtney Creeks from the right, then the Wenaha River from the left at the settlement of Troy.[14][15] From Troy, the terrain around the river becomes more open, with forests giving way to grassy ridges and rangeland.[16] The 27-mile (43 km) stretch between the Wallowa River confluence and Wildcat Creek is inaccessible by road.[6]

The Grande Ronde flows northeast, entering Asotin County, Washington at Horseshoe Bend, where it crosses the state border three times (into Washington, back into Oregon and into Washington again). It receives Menatchee and Cottonwood Creeks from the left, then is crossed by State Route 129 on the Grande Ronde River Bridge at Boggan's Oasis southwest of Anatone.[17][18] Below here, the river cuts through progressively more arid, sparsely vegetated landscapes with large areas of exposed rock.[16] It is joined by Joseph Creek from the right before emptying into the Snake River at the unincorporated community of Rogersburg, 24 miles (39 km) upstream of Asotin, Washington and 169 miles (272 km) upstream of the Snake's confluence with the Columbia River.[19]

Discharge

[edit]By discharge, the Grande Ronde is the third largest tributary of the Snake River.[n 1] Although water is diverted off the upper river for irrigation, water consumption in the Grande Ronde Valley represents only about 9 percent of its flow at the mouth,[4][22]: 3.9 and with no large dams regulating its flow, the Grande Ronde runs high with spring snowmelt and reaches its lowest level in the fall.[16] The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has only one operational stream gage on the Grande Ronde, located downstream of the Wenaha confluence near Troy. The station measures runoff from an area of 3,275 square miles (8,480 km2), or about 80 percent of the entire watershed.[4] The mean annual discharge between 1944 and 2023 was 3,016 cubic feet per second (85.4 m3/s), with a record high of 51,800 cubic feet per second (1,470 m3/s) on February 9, 1996, and a low of 344 cubic feet per second (9.7 m3/s) on August 20, 1977.[4] Mean monthly discharge ranged from a high of 7,329 cubic feet per second (207.5 m3/s) in May to a low of 721 cubic feet per second (20.4 m3/s) in September.[4]

The USGS also measured stream flow at several other locations along the river. At La Grande, just before the river enters the Grande Ronde Valley, the average discharge was 389 cubic feet per second (11.0 m3/s) for the period 1903–1989. This was from a drainage area of 678 square miles (1,760 km2), or 16 percent of the entire Grande Ronde watershed.[23] At Elgin, the average discharge was 670 cubic feet per second (19 m3/s) for the period 1955–1981, from a drainage area of 1,250 square miles (3,200 km2), or 30 percent of the entire watershed.[24]

Watershed

[edit]The Grande Ronde River's watershed is located mostly in Union and Wallowa Counties in Oregon and Asotin County in Washington, with small parts extending into Umatilla County, Oregon and Columbia and Garfield counties in Washington. The Blue Mountains, mostly rising to about 7,700 feet (2,300 m), form the western boundary of the watershed as they extend through northeast Oregon and southeast Washington. East of the Grande Ronde Valley are the Wallowa Mountains, whose highest peaks reach almost 10,000 feet (3,000 m).[25]: 15 Due to their higher elevation, the Wallowas were shaped by heavy Ice Age glaciation, leading to their nickname of the "Oregon Alps".[26] The Wallowa Valley, the second major mountain valley in the Grande Ronde watershed, is situated just north of the Wallowa Mountains; the Wallowa River drains this area into the Grande Ronde.[6][25]: 16 The northeastern part of the Grande Ronde watershed, north of the Wallowa Valley and west of Hells Canyon, is defined by extensive flat-topped plateaus through which the river and its tributaries have cut canyons, creating a dissected plateau.[27]: 6–7

Most of the river's 4,105-square-mile (10,630 km2)[3] watershed is in Oregon; only 341 square miles (880 km2), or 8 percent, are in Washington.[25]: 15 The U.S. Geological Survey considers the Upper Grande Ronde sub-basin to be the section upstream of the Wallowa River, with the Lower Grande Ronde sub-basin extending from there to the Snake River. The Upper Grande Ronde is 1,635 square miles (4,230 km2), or about 40 percent of the total; the Lower Grande Ronde is 1,517 square miles (3,930 km2), or about 37 percent. The Wallowa River sub-basin accounts for the remaining 953 square miles (2,470 km2), or 23 percent of the whole.[3]

The watershed is mostly rangeland and forest, with agriculture limited to the Grande Ronde and Wallowa Valleys. Population density is light at about 16.6 persons per square mile (6.4/km2).[28]: 648 The largest city is La Grande, which as of the 2020 census had a population of 13,026.[29] Other major towns include Union (2,152) in the southern Grande Ronde Valley, and Enterprise (2,052) in the Wallowa Valley.[30][31] About 46 percent of the watershed is public land, managed primarily by the U.S. Forest Service and the U.S. Bureau of Land Management.[25]: 21 Most of the Wallowa Mountains, and the Grande Ronde's headwaters in the Elkhorn Mountains, are in the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest. The Blue Mountains to the north are mostly in the Umatilla National Forest.[6]

The Grande Ronde watershed experiences a continental climate with warm, dry summers and cold, moderately snowy winters. Mean temperatures range from a daily minimum 24 °F (−4 °C) in January to a daily maximum of 84 °F (29 °C) in July. Annual precipitation ranges from 14 inches (360 mm) in the valleys to 60 inches (1,500 mm) at higher elevations. Most precipitation in the Grande Ronde watershed falls as snow.[25]: 17 Due to the lower elevation of the Blue Mountains, snowmelt occurs earlier in the upper Grande Ronde drainage, typically peaking in March or April; the Wallowa River, by contrast, peaks in May or June.[25]: 25

The Grande Ronde watershed is bordered by several other watersheds of the Columbia River basin. To the west are the watersheds of the Walla Walla, Umatilla and John Day Rivers, which all flow directly into the Columbia River. The Tucannon River and Asotin Creek to the north, the Imnaha River to the east, and the Powder River to the south are all tributaries of the Snake River.[3]

Geology

[edit]

The Grande Ronde River basin is founded on multiple terranes, or crustal fragments, that accreted onto the North American continent during the Mesozoic 248–65 million years ago (Ma). At that time, the area was still part of a shallow inland sea. About 160–100 Ma, multiple igneous plutons intruded into the crust beneath this area, the largest of which would eventually form the Wallowa Mountains as the region experienced tectonic uplift that raised the land above sea level.[26] The general outline of the Columbia River basin and its tributaries began to take shape about 40 Ma.[32]: 288

The ancestral topography and drainage patterns were completely altered between 17–6 Ma with the eruption of the Columbia River basalts, a series of massive flood basalt events that engulfed much of eastern Washington and Oregon in the region now known as the Columbia Plateau.[26] In parts of the Grande Ronde River basin, the basalt layers are more than 5,000 feet (1,500 m) thick.[33] The Grande Ronde basalt sub-group erupted between 17 and 15.5 Ma and accounts for more than 80 percent of the total volume of the flows.[26]

The outline of the Grande Ronde watershed began to take shape about 14 Ma, as tectonic uplift combined with the effects of basalt eruptions blocked westward drainage from the region to form a large geologic depression, the "Troy basin".[33] A landscape of shallow lakes and peat bogs developed; over millions of years, layers of peat were buried under sediment, forming lignite (low-grade coal) seams which appear in the Grouse Creek area near Troy.[33][34] By 10 Ma the area had begun to drain northeast down an ancestral Grande Ronde river channel.[33] Some of the later basalt eruptions flowed down this channel and spread over southeastern Washington.[33] At this time, the land was still relatively flat and the river formed a meandering course through the developing soils atop the basalt layers.[26]

From the end of the basalt eruptions around 6 Ma, the rate of uplift greatly increased as the present-day Blue Mountains began to rise.[33][26] As the land rose, the river's gradient increased and it began to incise into the landscape, entrenching its meanders and resulting in the river's twisting course through its lower canyons.[26] Along the lower Grande Ronde, the canyons have cut through and exposed the horizontal basalt layers, forming distinctive terraced cliffs. Although the Columbia River basalts encompass almost all the surface geology of the area, older rocks are exposed in a few places, including the Wallowa and Elkhorn mountains, and along the lower river in Washington where it cuts into rock below the basalt layers.[25]: 16 In contrast, the Grande Ronde Valley was formed as a large graben, or fault-block, dropped below rising mountains on either side. Alluvial sediment deposits, up to 2,000 feet (610 m) thick in places, form the flat valley floor.[35]: 50–51

History

[edit]Indigenous peoples

[edit]

The lower Grande Ronde watershed downstream of the Grande Ronde Valley was once within the territory of the Nez Perce.[27] The higher elevations in the Blue Mountains to the west were used by the Nez Perce and multiple Columbia Plateau tribes, who traveled to these areas in summer to hunt, fish and gather roots and berries. The Grande Ronde headwaters above the valley were considered Cayuse territory.[36]: 8–9 The Grande Ronde Valley itself was a major rendezvous site for the Nez Perce and tribes west of the Blue Mountains such as the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla.[37][27]: 19–21 The Shoshone from the south would also visit the area.[38]: 45 The valley was a place to trade and peacefully settle disputes, as well as to fish, bathe in hot springs, and bring the elderly and sick to recuperate.[39]: 113

People came to the Grande Ronde region via an extensive network of trails that laced the Blue Mountains. Trails connected the Grande Ronde Valley southeast to the Baker Valley, west to the Umatilla River valley, and north to the Walla Walla Valley.[27]: 19–21 A major trail used by the Nez Perce ran from their villages at the Snake and Clearwater River confluence (modern-day Lewiston) up Asotin Creek and down to the Grande Ronde near the Wenaha River. From there it followed the Grande Ronde to Indian Valley where a branch crossed east towards the Wallowa Valley.[27]: 21–23 The Wallowa Valley was a favorite hunting ground for the Wallowa band of Nez Perce, which in the 1870s was led by Chief Joseph. The Wallowa migrated seasonally on this route from winter villages on the lower Grande Ronde and Snake, gathering roots on high prairies in spring, and hunting and fishing in the Wallowa Valley in late summer and fall.[40]

The Nez Perce and Cayuse called the upper section of the Grande Ronde Qapqápnim Wéele, meaning "cottonwood stream".[41]: 171 The joining of this stream with the Wall-low-how or Wallowa River formed the Way-lee-way, or the lower section of what is now the Grande Ronde.[27]: 26 An important fishing village, Qapqápa, was located at present-day La Grande. Upstream of there, the river was known as ʔIyéexeteš, "foaling area", by the Cayuse.[41]: 168 The Cayuse and Walla Walla had a fishing village on the Grande Ronde called ʔUnéhe, near Courtney Creek upstream of the mouth of the Wenaha River.[41]: 176 The Nez Perce had several villages on the Grande Ronde below the Wenaha, including Híinezpu at the mouth of Bear Creek, and Qemúynem at the confluence with the Snake River.[41]: 184–185

A Nez Perce legend tells that the course of the lower Grande Ronde was created by Beaver, after he stole fire from the pine trees in the Blue Mountains to bring to the other animals so they could warm themselves.[42]

"The Pine trees started after him. When they were close behind him, Beaver darted from one side of the river to the other, from one bank to the other. When they stopped for breath, he swam straight ahead. That is why the Grande Ronde River today winds and winds in some places and flows straight along in other places. It follows the directions Beaver took when he was running with the coal of fire."[43]: 119

Exploration and settlement

[edit]The Grande Ronde Valley was explored and named by fur trappers in the early 19th century. In 1811 the Pacific Fur Company chartered an expedition, led by Wilson Price Hunt, to find a passage from the upper Snake River to the Pacific Ocean. Finding Hells Canyon to be impassable for boats, the expedition followed Native American trails on an overland route through the Blue Mountains.[44][45]: 35 Starving and exhausted, they stumbled across the Grande Ronde Valley on Christmas Day, and replenished their supplies by trading with the natives.[45]: 35 [46]: 192 French-Canadian fur trappers who subsequently visited the area dubbed it Grande Ronde, meaning "great circle", a name which was recorded by Peter Skene Ogden in 1827. Ogden also referred to the river as the "Clay River", the origin of which is not known.[47]: 147

U.S. Army officer Benjamin Bonneville explored the lower Grande Ronde River on an 1834 expedition, after also failing to find a way down the Snake through Hells Canyon. Bonneville's party crossed the Wallowa Mountains and down Joseph Canyon to reach the Grande Ronde, recording the name "Way-lee-way". At the confluence they encountered the winter camp of Chief Tuekakas and the Wallowa Nez Perce.[48] Bonneville also called the river Fourche de Glace, "river of ice".[47]: 147 In 1843, John C. Frémont surveyed the Grande Ronde Valley for the Corps of Topographical Engineers. Emphasizing the agricultural potential of the valley, he described it thus:

"... a beautiful level basin, or mountain valley, covered with good grass on a rich soil, abundantly watered, and surrounded by high and well timbered mountains; and its name descriptive of its form the great circle. It is a place one of few we have seen in our journey so far where a farmer would delight to establish himself, if he were content to live in the seclusion it imposes."[49]

Starting in the 1840s, settlers began to move through the area on the Oregon Trail, which passed through northeast Oregon roughly following the route of the Hunt expedition.[44] From Idaho, the trail traveled up the Burnt River and through Baker Valley before entering the Grande Ronde Valley via Ladd Canyon. Passing through La Grande, it crossed the Grande Ronde River upstream at what is now Hilgard Junction State Park, before diverging northwest along what is now the I-84 route towards present-day Pendleton.[27]: 19–20 [50] Moses "Black" Harris led the first wagon train through the Grande Ronde Valley in 1844.[51]: 105–106

The fertile, well-watered valley, with its grasslands offering rich forage for animals, was a welcome respite after traveling through the deserts of eastern Oregon and Idaho. Native Americans in the valley engaged in a lucrative trade of oxen, trading one healthy, well-fed animal for every two exhausted, starving ones. They let the oxen graze and fatten up in the valley before selling them to the next party of travelers.[52] An estimated 300,000 emigrants traveled through the Grande Ronde Valley from the 1840s to the 1870s.[25]: 19

As the wave of settlement spread to northeast Oregon, the 1850s saw increasing hostilities between Native Americans and settlers, particularly after the 1847 Whitman Massacre.[53] The Walla Walla, Cayuse and Umatilla surrendered their lands in the upper Grande Ronde River in the 1855 Treaty of Walla Walla in exchange for the Umatilla Indian Reservation, although they "reserved their right to hunt, fish and gather at all usual and accustomed areas on and off the reservation."[54][55] On July 17, 1856, a U.S. Army detachment led by Col. Benjamin F. Shaw killed fifty or sixty mostly unarmed Walla Walla, Umatilla and Cayuse near present-day Elgin, in what is now known as the Grande Ronde Massacre. This further inflamed tensions and led to the failure of peace talks in 1856.[56][57] In 1862, settlers began homesteading in the Grande Ronde Valley and a group of Umatilla attempted to prevent them from claiming land. Soldiers sent to deal with the dispute ended up killing four Umatilla men, causing the rest of the group to flee. This brought an end to tribal resistance of settlement in the valley.[58]

The Nez Perce retained control of their lands along the lower Grande Ronde River in the 1855 treaty.[59] However, gold strikes near Lewiston led to a flood of prospectors onto Nez Perce treaty lands in the 1860s. Some Nez Perce leaders were pressured into signing a second treaty that greatly shrank the size of their reservation, eliminating all the lands in Washington and Oregon, and thus the Grande Ronde watershed, from their use.[60] Several Nez Perce bands, including that led by Chief Joseph, refused to leave their lands in northeast Oregon. Joseph's band held out in the Wallowa Valley until the Nez Perce War of 1877, when they were forced to flee ahead of the US Army's arrival.[61][62]

Later development

[edit]

The Grande Ronde Valley became well established as an agricultural center in the 1860s and 1870s, providing food to gold mining districts in Idaho to the east.[37] La Grande, founded in 1862, was the first permanent American settlement in northeast Oregon.[63] Within a few years, farmers and ranchers had dug ditches, rerouted and channelized streams to drain the area's natural wetlands. Timber cut in the surrounding mountains was floated down the Grande Ronde and Catherine Creek to sawmills in the valley.[10]: 27–30 Gold was also discovered in Tanner Gulch near the river's headwaters in 1862, and from the 1870s to the early 1900s the area hosted placer mining operations. The community of Hilgard developed on the old Oregon Trail about 5 miles (8.0 km) west of La Grande, as a supply point for miners, ranchers and loggers.[64]: 11

In 1884 the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company (OR&N) built its tracks through the valley, connecting the area to Portland by rail. By 1890 the OR&N had constructed a branch line to Elgin; in 1907 it was extended to Joseph in the Wallowa Valley.[65] The rail line follows the winding Grande Ronde River canyon from Elgin to Rondowa, where it turns east up the Wallowa River canyon.[6] It was primarily used to haul wood, grain and livestock and had a regular passenger service until 1960. The Wallowa Union Railroad Authority now operates the line; since 2004 it has hosted a heritage rail service, the Eagle Cap Excursion Train,[66] between Elgin and Joseph.[65]

During the 1860s, gold prospecting from Lewiston soon extended up the Snake to the Grande Ronde's mouth, following rumors of a massive gold discovery on Shovel Creek, which flows into the Snake a short distance upstream from the Grande Ronde. By 1865 the Rogers brothers had established Rogersburg at the confluence of the Grande Ronde and Snake.[67] Although the Rogers laid out the townsite with plans to sell lots, the town failed to grow because of the lack of road access.[68] Steamboats on the Snake River were the primary means of transportation between Lewiston, the mouth of the Grande Ronde and points upstream. Mining traffic ceased in 1904, though boats started carrying passengers and mail again around 1910.[69]: 23–24 [70]: 2276–2277 The mouth of the Grande Ronde remained inaccessible by road until 1937.[68]

The rugged, relatively inaccessible area around Troy was not settled until near the turn of the 20th century. William Adams and his wife Lou homesteaded near the Grande Ronde in 1893; their isolation in the wilderness prompted comparisons to Adam and Eve, and the well-timbered plateau between the Grande Ronde and Wenaha became known as "Eden Ridge".[27]: 53 Over the next few years more settlers arrived, and the first building in Troy was established in 1902.[27]: 56 By 1904, a rough road had been constructed from Elgin to Eden. The 40-mile (64 km) route through mountainous terrain was "a huge job for the small number of settlers".[27]: 75–76

With most of this land unsuitable for agriculture, the primary industry became livestock grazing. By the time the Wenaha Forest Reserve (now the Wenaha Ranger District of the Umatilla National Forest) was established in 1905, about 200,000 sheep, 40,000 cattle and 15,000 horses grazed in the area.[71] The forest reserve was established in order to settle land disputes between cattle and sheep ranchers,[27]: 62–66 and to protect the watershed from overgrazing.[71] The canyons of the lower Grande Ronde were used for wintering livestock as well as growing fruits and vegetables. By the 1930s, many of the original homesteaders had sold out, and ranches consolidated into fewer, larger operations.[72]: 34 Although livestock is still one of the region's main industries, some parts of the Grande Ronde watershed have since been closed to grazing. In what would become the Wenaha-Tucannon Wilderness, grazing allotments were cancelled around 1965.[73]: 28

A number of dams were proposed for the Grande Ronde throughout the 20th century, though none were built. In 1944 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation proposed several dams on the upper Grande Ronde and Catherine Creek in response to repeated flooding in the Grande Ronde Valley. Congress authorized the flood control dams in 1968, but they were delayed due to environmental concerns. After the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation sued in 1974, the dam projects were "indefinitely postponed".[10]: 30–31 Downstream of Troy, the Wenaha Dam was proposed in 1963 for flood control and power generation. This 550-foot (170 m) high rockfill dam would have backed water more than 30 miles (48 km) up the Grande Ronde River.[74]: 93–96 On October 28, 1988, the Grande Ronde was designated a Wild and Scenic River from the Wallowa River to near the Oregon–Washington border, making the section off limits to new dams.[75]

Ecology

[edit]Fish

[edit]

The Grande Ronde River supports an estimated 38 fish species, of which 15 are introduced.[28]: 648 Like many rivers in the Columbia Basin, it once supported large runs of anadromous fish, which migrate from the Pacific to spawn in freshwater streams. These fish formed a major part of the diet for indigenous peoples in the region.[76] Chinook salmon, steelhead and bull trout are federally listed as threatened species;[25]: 36–37 their numbers have fallen due to dam construction along the Columbia and Snake Rivers and habitat degradation in the Grande Ronde river system.[10]: 42 [77] Sockeye salmon, which primarily spawned in Wallowa Lake, have been extirpated from the basin since the early 1900s,[78]: 33 though Kokanee (landlocked sockeye) are still present in Wallowa Lake.[25]: 37 The Grande Ronde was once the largest producer of coho salmon in the Snake River system, but the wild coho run had also disappeared by 1986.[78] Hatchery coho were reintroduced to the Grande Ronde watershed in 2017.[79]

The Grande Ronde River watershed has between 3,000 and 4,000 miles (4,800 and 6,400 km) of current or former salmon-bearing streams.[80] Historically, twenty-one tributaries of the Grande Ronde supported salmon spawning, but by 1995, only eight tributaries did so.[77] Before the turn of the 20th century, an estimated 20,000 spring chinook salmon spawned in the river, which had declined to 12,200 by 1957 and to just over 1,000 in 1992.[10]: 33 Steelhead returns fell from about 16,000 in the 1960s to 11,000 in the 1990s.[72]: 25 Water quality in the Grande Ronde basin has been impacted by logging, livestock grazing and agriculture, which have led to increased sedimentation rates and stream temperatures, and reduced water flows in late summer.[77] In 1982 the Lookingglass Fish Hatchery was built to rear chinook salmon on Lookingglass Creek, a tributary of the Grande Ronde. The hatchery was one of several built throughout the Snake River system as part of the Lower Snake River Compensation Plan, to mitigate anadromous fish losses caused by dam projects.[81][82]

In 1992, the Northwest Power Planning Council organized the Grande Ronde Model Watershed (GRMW) project to develop a comprehensive management strategy for the Grande Ronde and adjacent Imnaha River watersheds. The GRMW is intended to foster cooperation between public agencies, private landowners, fisheries management and environmental interests.[83] Funded primarily by the Bonneville Power Administration, it has coordinated hundreds of projects in the Grande Ronde River basin to conserve instream flows, remove fish passage barriers, mitigate erosion and restore riparian habitats. However, chinook salmon and steelhead returns have not increased substantially in the 1992–2023 period,[80] due to the effects of the Snake and Columbia River dams on fish migration.[84]

Bull trout, once widely distributed in Oregon, now inhabit only a few streams due to the effects of logging, mining and agriculture. The Grande Ronde, Wenaha, and Wallowa Rivers and their tributaries host eleven surviving bull trout populations.[85] Redband trout and Pacific lamprey are federally designated species of concern.[25]: 38 Other native and introduced fish species in the Grande Ronde watershed include mountain whitefish, brook trout, northern pikeminnow, peamouth chub, longnose dace, speckled dace, redside shiner, largescale sucker, bridgelip sucker and mountain sucker.[28]: 648

Plants and animals

[edit]

The Grande Ronde watershed occupies the eastern part of the Blue Mountains ecoregion, which is home to about 13 amphibian species, 285 bird species, 92 mammal species, and 21 reptile species.[25]: 37 Rocky Mountain elk were widespread in the region for thousands of years, but their populations were almost eliminated by the 1880s due to hunting and habitat encroachment. Elk were reintroduced in the early 1900s. As of 2020, the Blue Mountains elk herd which ranges in the northern part of the Grande Ronde and Wenaha drainages numbered just over 4,000 head.[86] Much of the Grande Ronde is also located within gray wolf range in Oregon. Union and Wallowa Counties each have eight known wolf packs.[87] The range of four wolf packs in Washington also extends into or adjacent to the Grande Ronde watershed.[88] The river bottoms also provide wintering habitat for bighorn sheep, elk, mule deer, white-tailed deer and bald eagles.[89]

Grasslands dominated by bluebunch wheatgrass, sheep fescue and giant wildrye were once widespread across the watershed. Most of the original grasslands have been replaced by agriculture or heavily altered by livestock grazing, which has caused erosion and introduced invasive plants such as cheatgrass.[25]: 19 The Grande Ronde watershed includes part of the 146,000-acre (59,000 ha) Zumwalt Prairie, the largest intact bunchgrass prairie in the Pacific Northwest.[90] Higher elevations transition into shrubland and eventually coniferous forest in the Blue and Wallowa Mountains. As elevation increases, principal tree species transition from ponderosa pine to Douglas-fir, grand fir, subalpine fir and mountain hemlock.[25]: 19

The Grande Ronde Valley was once home to extensive wetlands. The perennial Tule Lake was located in the southern part of the valley, where the Grande Ronde and Catherine Creek converged to form the most significant area of wetlands. The lake fluctuated from 1,600 to 2,300 acres (650 to 930 ha) in size, expanding to more than 10,000 acres (4,000 ha) in especially wet years.[10]: 24 Beaver were widespread, and their ponds were a major factor in forming wetlands, creating a diversity of water depths and vegetation communities that provided shade and food sources for salmon and other fish.[10]: 24 Robert Stuart, a member of Hunt's 1811 expedition, described the wetlands as such:

"This plot is at least six miles in circumference, in but few places swampy, of an excellent soil, and almost a dead level; with the Glaize [Grande Ronde] and its two branches meandering in every direction through it – the banks of these streams are high and muddy, covered in particular places with dwarf Cottonwoods, and the residue in a large growth of Willows, which afford an inexhaustible stock of food for the incredible multitudes of Furr'd race who reside in their bosoms, but the S. East fork [Catherine Creek] excels both the others, particularly in the number of its inhabitants of the Otter tribe – a few Deer and Racoon are the only animals you may add to the Elk, Beaver and otter as being natives of this tract."[91]: 3

Fur trappers eradicated beaver from the area and settlers drained most of the wetlands for agriculture in the 19th century. The State Ditch diverted the Grande Ronde River away from this flood-prone lowland area, leaving Catherine and Ladd Creeks as the only surface water inflows.[10]: 52 In 1949, Ladd Marsh Wildlife Area was established in the southern part of the valley to conserve wetland habitat for migrating waterfowl. This is now the largest tule wetland remaining in northeast Oregon.[92]

Industries and economy

[edit]Irrigation is the largest consumer of Grande Ronde River water.[22]: ES-6 The Grande Ronde Valley has about 100,000 acres (40,000 ha) of irrigated farmland,[93] consuming 211,000 acre-feet (260,000,000 m3) of surface water and 87,000 acre-feet (107,000,000 m3) of groundwater each year. Municipal and industrial users consume about 10,000 acre-feet (12,000,000 m3) of combined surface and groundwater.[22] Some of this water re-enters the river via irrigation return flows. There are eighteen small reservoirs in the upper Grande Ronde basin upstream of the Wallowa River, most of which store water for irrigation or recreation purposes. None of these reservoirs are on the main stem of the river, and their impact on the river's overall flow is negligible. As a consequence, irrigators mostly depend on the natural availability of water, which can vary significantly from year to year.[22] Another 183,000 acre-feet (226,000,000 m3) of surface water are used for irrigation in the Wallowa Valley. A dam regulates the level of Wallowa Lake to store up to 42,750 acre-feet (52,730,000 m3); this is the largest surface water storage facility in the Grande Ronde River system.[94]

While water flows in the Upper Grande Ronde River Basin typically peak in March and April, agricultural water demand is highest in June and July.[22] On average, the valley experiences an annual water supply deficit between about June and November.[22] In late summers of dry years, irrigation diversions often leave very little water to flow out of the Grande Ronde Valley. Water deficits are most severe in the southern part of the valley, in the Catherine Creek sub-basin.[22] On the other hand, spring snowmelt presents a high flood risk, due to the area's naturally flat topography and the redevelopment of wetlands and floodplains that once buffered high flows.[22] As of 2022, the state of Oregon was funding plans for off-stream reservoirs, groundwater recharge, water conservation and floodplain restoration in order to mitigate spring flooding and summer water shortages in the Grande Ronde Valley.[95]

Logging has been a major industry in the Grande Ronde watershed since settlement in the 1860s. A water-powered sawmill was first built on the river in 1862 at Oro Dell, just upstream of La Grande.[64]: 11 By 1890, the Grande Ronde Lumber Company had acquired large tracts of timberland in the upper Grande Ronde watershed. Several splash dams were constructed to store water for annual log drives down the river.[64]: 12 Around the turn of the 20th century, about 10–20 million board feet of logs were floated down the river each year to mills in La Grande.[64]: 11 In 1926, the Mount Emily Lumber Company acquired the Grande Ronde Lumber Company's holdings. The river drives ended, with log hauls switching to rail, and later to truck.[64]: 12

In the mid-20th century, logging on federal (National Forest) lands increased greatly in both Union and Wallowa Counties, but the rate of harvest dropped off by the 1990s, with private industry making up the bulk of timber harvest in the 21st century. In 2004, about 118 million board feet were cut in Union and Wallowa Counties, compared to 200–300 million board feet per year in the 1960s–1980s.[96] Although the river is no longer used for log transport, the effects of timber harvest continue to impact its tributaries. In many places, reduced forest canopy cover has elevated stream temperatures, to the detriment of cold-water fish such as trout and salmon. Since the 1970s, improved logging practices such as stream buffer zones have reduced the impact of timber harvest on the Grande Ronde.[97]: 35

Early gold mining along the river's headwaters was followed by dredge mining in the 1930s and 1940s that deposited tailings along more than 2 miles (3.2 km) of the riverbed. The tailings buried the natural floodplain and forced the river into a constricted channel on the west side of the valley.[98] Starting about 2010, the Forest Service has conducted restoration work along this reach.[99]

Recreation

[edit]

Several sections of the Grande Ronde and its tributaries are federally protected as National Wild and Scenic Rivers. The Wild and Scenic section of the Grande Ronde extends for 43.8 miles (70.5 km) from Rondowa, at the confluence of the Wallowa River, to the Oregon–Washington state line. The roadless stretch from Rondowa to Wildcat Creek is designated "Wild", and from there downstream is "Recreational".[89] The Wallowa River is designated "Recreational" for 10 miles (16 km) from Minam to its confluence with the Grande Ronde.[100] The entire 21.6-mile (34.8 km) main stem of the Wenaha River is protected, with the section in the Umatilla National Forest designated "Wild", and from there to Troy as "Scenic" and "Recreational".[101] Parts of three other streams in the Grande Ronde watershed – the Minam River, Lostine River and Joseph Creek – also carry Wild and Scenic designations.[102][103][104]

The Grande Ronde River is considered one of the top recreational fisheries in the Pacific Northwest, particularly for steelhead/rainbow trout and chinook salmon.[89] Steelhead fishing is typically best from September or October to early December, when water temperatures fall low enough to draw steelhead out of the Snake River. Only hatchery fish with clipped adipose fins may be kept.[105]: 285 Fly fishing for trout is good along the Wild and Scenic stretch in Oregon. Smallmouth bass are common in the lower river in Washington.[105]: 287 The Grande Ronde's tributary, the Wenaha River, is one of only a few Oregon rivers where fishing for bull trout is permitted (catch-and-release only).[106] Because the 1855 Treaty of Walla Walla grants rights to Umatilla and Nez Perce subsistence fishing in the Grande Ronde River, the allowable harvest of fall chinook is apportioned evenly between the sport and subsistence fisheries.[78]: 17

Along the Oregon–Washington border, the river is accessible by road from Powwatka Bridge (Wildcat Creek) 8 miles (13 km) upstream from Troy, to Shumaker Creek about 10 miles (16 km) downstream from Boggan's Oasis. The mouth of the river is also reachable by road from Asotin.[6] While the Wild section of the Grande Ronde is entirely on the Umatilla National Forest, the Recreational section passes through a mix of public and private lands. Several public access points are maintained along this stretch.[107] From this reach upstream to the Wallowa River confluence and down to the Snake River, the Grande Ronde is accessible only by boat. Fishing is often done from drift boats and rafts, and several private outfitters run multi-day floating trips on the river.[105]: 287

Due to its abundant wildlife, the Grande Ronde area is frequented by hunters. Big game hunting for elk, deer, mountain goat, bighorn sheep, black bear and mountain lion draws about 40,000 people each year to the Umatilla National Forest.[108] chukar, partridge and quail are common in riverside and grassland areas, and turkey and grouse are common in the upland forested areas.[109] Due to the lack of roads, many hunters use boats on the river to access remote areas.[110]: 51 Bird hunting locations near the river include the Wenaha Wildlife Area around Troy, and parts of Ladd Marsh in the Grande Ronde Valley.[111][112]

The Grande Ronde has mostly beginner to intermediate level whitewater (class II-III), and is heavily used by rafters and kayakers. The Wallowa River at Minam is the main launching point for the Wild and Scenic section of the river. It usually takes 2–3 days to float the Wild and Scenic stretch from Minam to the Oregon–Washington border.[113] There are no maintained camping facilities along most of the river. Primitive campsites on the river are available on a first-come, first-served basis. Boaters can also access the river at Powwatka Bridge, Mud Creek, Troy, Boggan's Oasis and Shumaker Creek.[113] Many boaters from Minam take out at Powwatka Bridge or Troy, while another popular shorter float is from Troy down to Boggan's Oasis or Shumaker Creek. From Shumaker down to the mouth, there is no direct return by road.[105]: 285 [114]: 352–355

Because the river is free-flowing, water levels can rise or fall quickly depending on precipitation and snowmelt. The most popular boating season is from about May to July. Before May, the river is typically running too high with spring melt, and by August water levels have fallen enough to expose numerous rocks and shoals.[113] The Narrows, located about 5 miles (8.0 km) from the confluence with the Snake, is the only Class IV rapid on the Grande Ronde and is considered quite dangerous, especially at low water during which the river constricts into a small bedrock chute.[113][114]: 354 All river trips require registering for a free permit from the Bureau of Land Management, which administers watercraft use of the river.[113]

See also

[edit]- List of tributaries of the Columbia River

- List of rivers of Oregon

- List of rivers of Washington

- List of longest streams of Oregon

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Grande Ronde River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. September 10, 1979. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey. "U.S. Geological Survey Topographic Map: Anthony Lakes, Oregon quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data from The National Map". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "USGS Gage #13333000 Grande Ronde River at Troy, OR: Water-Data Report 2023". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey. "U.S. Geological Survey Topographic Map: Crawfish Lake, Oregon quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The National Map". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey. "U.S. Geological Survey Topographic Map: McIntyre Creek, Oregon quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey. "U.S. Geological Survey Topographic Map: Hilgard, Oregon quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey. "U.S. Geological Survey Topographic Map: La Grande, Oregon quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Catherine Creek Tributary Assessment" (PDF). Grande Ronde River Basin Tributary Habitat Program. U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. February 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2024. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey. "U.S. Geological Survey Topographic Map: Conley, Oregon quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey. "U.S. Geological Survey Topographic Map: Elgin, Oregon quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey. "U.S. Geological Survey Topographic Map: Rondowa, Oregon quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey. "U.S. Geological Survey Topographic Map: Promise, Oregon quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey. "U.S. Geological Survey Topographic Map: Troy, Oregon quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Wallowa/Grande Ronde River". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey. "U.S. Geological Survey Topographic Map: Mountain View, Washington quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey. "U.S. Geological Survey Topographic Map: Fields Spring, Washington quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey. "U.S. Geological Survey Topographic Map: Limekiln Rapids, Washington quad". TopoQuest. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ "USGS Gage #13342500 Clearwater River at Spalding, ID: Water-Data Report 2013" (PDF). National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "USGS Gage #13317000 Salmon River at White Bird, ID: Water-Data Report 2013" (PDF). National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Upper Grande Ronde River Watershed Partnership, Union County, Oregon: Place-Based Integrated Water Resources Plan" (PDF). Oregon Water Resources Department. January 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "USGS Gage #13319000 Grande Ronde River at La Grande, OR: Surface-Water Monthly Statistics". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved February 23, 2024.

- ^ "USGS Gage #13323500 Grande Ronde River near Elgin, OR: Surface-Water Monthly Statistics". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved February 23, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Grande Ronde Subbasin Plan" (PDF). Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission. May 28, 2004. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Caldwell, Dylan J. (June 18, 2007). "Geologic Controls on Physical Habitat Distribution, Grande Ronde River, Oregon and Washington" (PDF). Union County, Oregon. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Tucker, Gerald J. (1940). "History of the Northern Blue Mountains" (PDF). U.S. Forest Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 18, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c Benke, Arthur C.; Cushing, Colbert E., eds. (2005). Rivers of North America. Elsevier Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-088253-1.

- ^ "La Grande city, Oregon". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Union city, Oregon". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Enterprise city, Oregon". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ Moclock, Leslie; Selander, Jacob (2021). Rocks, Minerals, and Geology of the Pacific Northwest. ISBN 9781604699159.

- ^ a b c d e f Ferns, Mark L. (1985). "Preliminary report on Northeastern Oregon lignite and coal resources, Union, Wallowa and Wheeler Counties" (PDF). Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries. Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- ^ "Blue Mountains". Washington State Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ National Proceedings: Forest and Conservation Nursery Associations, General Technical Report PNW-GTR-389 (Report). U.S. Forest Service. 1996.

- ^ Final Environmental Impact Statement, Grande Ronde Planning Unit (Report). U.S. Forest Service. 1978.

- ^ a b Hartman, Rebecca. "La Grande". Oregon Encyclopedia. Oregon Historical Society. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ Langston, Nancy (2009). Forest Dreams, Forest Nightmares: The Paradox of Old Growth in the Inland West. University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295989686.

- ^ Cutler, Donald L. (2016). "Hang Them All": George Wright and the Plateau Indian War. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806156262.

- ^ Flanagan, John K. (January 1, 1999). "The Invalidity of the Nez Perce Treaty of 1863 and the Taking of the Wallowa Valley". American Indian Law Review. 24 (1). doi:10.2307/20070622. JSTOR 20070622. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Hunn, Eugene S.; Morning Owl, E. Thomas; Cash, Phillip E Cash; Engum, Karson Jennifer. Cáw Pawá Láakni, They Are Not Forgotten: Sahaptian Place Names Atlas of the Cayuse, Umatilla and Walla Walla. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-99026-2.

- ^ Sugiyama, Michelle Scalise. "How Beaver Stole Fire from the Pines". Talking Stories Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ Clark, Ella E. (2023). Indian Legends of the Pacific Northwest. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520350960.

- ^ a b Barry, J. Neilson (1911). "The First-Born on the Oregon Trail". The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society. 12 (2): 164–170. JSTOR 20609869. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ a b Fletchall, Bronwyn M. (2008). "The Farthest Post: Fort Astoria, the Fur Trade, and Fortune on the Final Frontier of the Pacific Northwest". College of William & Mary. doi:10.21220/s2-gqe9-6733. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ Ronda, James P. (1990). Astoria & Empire. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803289420.

- ^ a b McArthur, Lewis Ankeny (1928). Oregon Geographic Names. Koke-Chapman.

- ^ "Benjamin Bonneville Route". Historic Oregon City. April 2, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "Baker to La Grande". Oregon Secretary of State. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "National Park Service – National Trails". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ Billington, Ray Allen (1962). The Far Western Frontier: 1830–1860. New York: Harper & Row.

- ^ John, Finn J.D. (September 15, 2017). "Offbeat Oregon History: Grande Ronde Valley, Oregon Trail's Eden, used-oxen dealership". Columbia County Chronicle & Chief. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ Tate, Cassandra (April 3, 2013). "Cayuse Indians". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ Trafzer, Cliff. "Walla Walla Treaty Council 1855". Oregon Encyclopedia. Oregon Historical Society. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ Schroeder, James (October 17, 2023). "Walla Walla Council (1855)". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ Lang, William F. "Grande Ronde Massacre, 1856". Oregon Encyclopedia. Oregon Historical Society. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ Wilma, David (May 3, 2007). "Washington Territorial Volunteers kill 50 Cayuse in the Grande Ronde Valley on July 17, 1856". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "Report by William H. Rector, 1862". Oregon History Project. Oregon Historical Society. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "Treaty with the Nez Perces, 1855". Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "The Treaty Period". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "The story of Wallowa Valley tied to Chief Joseph". Wallowa County Chieftain. August 5, 2007. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "The Flight of 1877". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "Historic La Grande". The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Upper Grande Ronde River Tributary Assessment" (PDF). Grande Ronde River Basin Tributary Habitat Program. Grande Ronde Model Watershed. January 2014. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b "About". Joseph Branch Trail-with-Rail. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "Eagle Cap Excursion Train". Eastern Oregon Visitor's Association. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ "Rogersburg". Revisit Washington. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ a b "Boater's Guide Map 10 Feature Descriptions". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ Buckendorf, Madeline Kelly; Bauer, Barbara Perry; Jacox, Elizabeth (2001). "Non-Native Exploration, Settlement, and Land Use of the Greater Hells Canyon Area, 1800s to 1950s" (PDF). Hells Canyon Complex FERC No. 1971. Idaho Power. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ Hearings on H.R. 12858, 85th Congress (Report). U.S. Government Printing Office. 1958. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ a b Rakestraw, Lawrence (1955). "Reserves in Oregon, Boundary Work, 1897–1907". A History of Forest Conservation in the Pacific Northwest, 1891–1913. NPS History. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ a b Wallowa and Grande Ronde Rivers Final Management Plan/Environmental Assessment (Report). U.S. Bureau of Land Management. December 1993. Retrieved February 23, 2024.

- ^ USDA Forest Service (June 2015). "Wenaha Wild and Scenic River Comprehensive Management Plan" (PDF). National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 24, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Water Resource Development of the Columbia River Basin, Vol. IV. U.S. Government Printing Office. Jun 1958.

- ^ "Celebrating 50 Years of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Tribal Perspectives" (PDF). Idaho Governor's Office of Species Conservation. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b c Keefe, MaryLouise; Anderson, David J.; Carmichael, Richard W.; Jonasson, Brian C. (1995). Early Life History Study of Grande Ronde River Basin Chinook Salmon (PDF) (Report). University of North Texas Digital Library. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ a b c Hurtado, Joel A. (1993). "Grande Ronde River Basin Fish Management Plan" (PDF). Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Coho Salmon Return to Oregon's Grande Ronde". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. March 12, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ a b Mehaffey, K.C. (August 18, 2023). "NWPCC Hears About Watershed Project in NE Oregon". Clearing Up. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Lookingglass Hatchery Visitors' Guide". Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Lower Snake River Compensation Plan". Northwest Power and Conservation Council. Retrieved February 23, 2024.

- ^ "About the Grande Ronde Model Watershed". Grande Ronde Model Watershed. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Feldhaus, Joseph; et al. (2022). "Grande Ronde and Imnaha River basin Spring Chinook Salmon Hatchery Review" (PDF). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Grande Ronde Bull Trout" (PDF). Oregon Native Fish Status Report. Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Blue Mountains Elk Herd" (PDF). Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. May 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Specific Wolves and Wolf Packs in Oregon". Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Wolf packs in Washington". Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Grande Ronde River". National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Zumwalt Prairie". Conservation Gateway. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Grande Ronde River, Oregon: River Widths, Vegetative Environment, and Conditions Shaping its Condition, Imbler Vicinity to Headwaters" (PDF). U.S. Forest Service. May 1995. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Ladd Marsh Wildlife Area Visitors' Guide". Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Upper Grande Ronde River Watershed Partnership: Place-Based Integrated Water Resources Planning" (PDF). Union County, Oregon. April 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ Christensen, Niklas; Salminen, Ed (January 31, 2018). "Wallowa County Water Assessment". County of Wallowa. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Mason, Dick (July 6, 2022). "Water plan for Upper Grande Ronde Basin receives state level recognition". Bend Bulletin. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ Andrews, Alicia; Kutara, Kristin (2005). "Oregon's Timber Harvests: 1849–2004" (PDF). Oregon Department of Forestry. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Managing the Columbia River: Instream Flows, Water Withdrawals, and Salmon Survival. National Academies Press. 2004. ISBN 9780309091558.

- ^ "Upper Grande Ronde River Mine Tailings Project" (PDF). Columbia River Basin Federal Caucus. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Upper Grande Ronde Mine Tailings Restoration Project Phase II" (PDF). Grande Ronde Model Watershed. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Wallowa River". National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Wenaha River". National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Minam River". National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Lostine River". National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Joseph Creek". National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Shewey, John (2011). Complete Angler's Guide to Oregon. Wilderness Adventures Press. ISBN 9781932098860.

- ^ "Northeast Zone". eRegulations. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ "Grande Ronde River Wild and Scenic River" (PDF). U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Hunting". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Game Bird/Waterfowl". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved February 23, 2024.

- ^ Snake Wild and Scenic River Study Draft Report/Environmental Statement (Report). U.S. National Park Service. April 1979.

- ^ "Ladd Marsh Wildlife Area Game Bird Hunting" (PDF). Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved February 23, 2024.

- ^ "Wenaha Wildlife Area Management Plan" (PDF). Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. December 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Boating on the Wallowa and Grande Ronde Rivers" (PDF). U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ a b Landers, Rich; Hansen, Dan; Huser, Verne; North, Douglass (2008). Paddling Washington: Flatwater and Whitewater Routes in Washington State and the Inland Northwest. Mountaineers Books. ISBN 9781594852619.