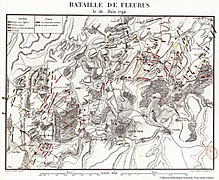

Battle of Fleurus (1794)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2023) |

| Battle of Fleurus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Low Countries theatre of the War of the First Coalition | |||||||

Jourdan at Fleurus with the balloon l'Entreprenant in the background. Painted by Mauzaisse in 1837; on display in the Galerie des Batailles, Versailles. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

70,000 infantry 12,000 cavalry 100 guns 1 balloon |

45,000 infantry 14,000 cavalry 111 guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 5,000, 1 gun[3] | 5,000, 1 gun[4][5] | ||||||

Location within Europe | |||||||

The Battle of Fleurus, on 26 June 1794, was an engagement during the War of the First Coalition, between the army of the First French Republic, under General Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, and the Coalition army (Britain, Hanover, Dutch Republic, and Habsburg monarchy), commanded by Prince Josias of Coburg, in the most significant battle of the Flanders Campaign in the Low Countries during the French Revolutionary Wars. Both sides had forces in the area of around 80,000 men but the French were able to concentrate their troops and defeat the First Coalition. The Allied defeat led to the permanent loss of the Austrian Netherlands and to the destruction of the Dutch Republic. The battle marked a turning point for the French army, which remained ascendant for the rest of the War of the First Coalition.

Background

[edit]In May 1794, Jean-Baptiste Jourdan was given the command of approximately 96,000 men created by combining the Army of the Ardennes with portions of the Army of the North and the Army of the Moselle. Jourdan was given the task of consolidating the capture of the north bank of the Sambre river, specifically by capturing the fortress of Charleroi, a task that the forces on the Sambre had tried three times and failed to accomplish, being defeated at the battles of Grandreng, Erquelinnes and Gosselies.[citation needed]

On 12 June, Jourdan's army crossed the Sambre for the fourth time and invested the fortress of Charleroi with 70,000 men. On 16 June, an Austrian-Dutch force of about 43,000 men counterattacked in heavy mist, inflicted 3,000 casualties, and drove Jourdan away from Charleroi back across the Sambre in the battle of Lambusart. While it was a setback, the French army withdrew from the field mostly in good order, and took little real damage from the battle. As a result, they were ready to go on the attack again within two days.[citation needed]

The third siege of Charleroi

[edit]The fifth crossing of the Sambre

[edit]

The defeat at Lambusart caused little damage to the French army, with Jourdan sustaining only 3,000 casualties out of a total of 90,000 men under command, of which 70,000 were engaged. Jourdan had withdrawn the army largely intact and in good order, and French morale remained high as all ranks felt that their loss was only due to the heavy mist, the element of surprise, and shortages of ammunition, not because of any deficiency of the French soldiers themselves.[citation needed]

As a result of these factors, Jourdan was quickly ready to go back on the offensive, and he recrossed the Sambre for the fifth time just 2 days after the battle of Lambusart, on 18 June.[citation needed]

The French divisions were to occupy much the same positions as they had during the fourth crossing and second siege of Charleroi. From west to east, they deployed as follows:[6]

- General Guillaume Philibert Duhesme’s division crossed at Aulnes Abbey and Landelies and positioned himself between the towns of Pieton and Souvret.

- General Anne Charles Basset Montaigu’s division (which replaced Muller's division in the attack force) crossed at Rus (south of the modern Terril du Hameau) and Landelies,[7] and deployed to the right of Duhesme with its right on the Pieton river.

- General Antoine Morlot’s division and General Jean-Joseph Ange d’Hautpoul’s brigade of cavalry crossed at Marchienne-au-Pont and deployed north of Gosselies with outposts at Thumeon (modern Thimeon)[7]

- General Jean-Etienne Championnet's division and General Guillaume Anselme Philibert de Soland's brigade of cavalry crossed at Marchienne-au-Pont and deployed between Heppignies and Wagnee,[8] with outposts in Mellet and St Fiacre (currently the company compound of Saspj De Munck Lionel & Maxime)[9]

- General François Joseph Lefebvre crossed at Chatellet and took position between Wagnee and the tavern of Campinaire (at the modern intersection of the N568 and N29),[8] with outposts in Fleurus

- General Jacques Maurice Hatry also crossed at Chatellet, and marched for Charleroi to resume besieging the fortress

- General Francois Severin Marceau, on the extreme right, crossed at Tergnee (around modern Rue du Tergnee in Farciennes) to take position from Campinaire to the northern edge of the forest of Copiaux (still existent today, south of Velaine-sur-Sambre), with detachments occupying Velaine, Baulet and Wanfersee (the latter two now combined into the town of Baulet-Wanfercee), and his main camp at Baratre (halfway between modern Lambusart and the town of Keumiee).[8]

From the moment of their deployments, the French divisions immediately began constructing entrenchments and redoubts to fortify their positions protecting the siege works.[citation needed]

Allied miscalculations and reactions

[edit]Jourdan's recrossing of the Sambre so soon after Lambusart caught the Allies completely by surprise.[citation needed]

Following the previous battle at Lambusart, the Allied high command under Feldmarschall Prince Coburg had assumed that the French were morally and materially beaten, and would be unable or unwilling to undertake another offensive after four successive failures. As a result, on 17 June, William V, the Prince of Orange, in command of the forces of the Allied left wing that defended this front, had spread out his forces again, sending a division under General Paul Davidovitch to Erquelinnes[10] while simultaneously preparing to send 4 battalions of infantry to reinforce Coburg's centre at Tournai. Orange's main force was at Chapelle-lez-Herlaimont.[citation needed]

Such was the Allied confidence that the French would not dare make another attempt on Charleroi, that even when the French recrossed the Sambre a fifth time, Orange concluded erroneously that they were aiming for Mons, the original objective of the Sambre campaigns.[11]

Orange ordered his outnumbered force at Chapelle-lez-Herlaimont to withdraw to the main base at Rouveroy to defend Mons and avoid being cut off by French advances. The 4 battalions intended for Coburg were withheld while Beaulieu's corps, which had returned to guard Namur after Lambusart, was ordered to assemble near Quatre-Bras to cover the road to Brussels.[citation needed]

As a result, the French once again effected their crossing unopposed.[citation needed]

Siege operations

[edit]The third siege of Charleroi commenced formally on 19 June with the city's investment, which the garrison, only 2,800 men strong under one Colonel Reynac,[12] was too weak to delay, especially since no one had expected the French to attack again so soon. With only three days between the raising of the second siege and the commencement of the third one, the garrison had neither had time to prepare for a new siege, nor destroy the works from the previous one.[citation needed]

During the third siege, the French benefitted from the reuse of the works from the second siege, giving them a headstart in speed and progress.[citation needed]

As the siege progressed, the various divisions of the army undertook several small divisional operations to clear enemy forces from their perimeter and keep Allied observation forces at a distance.[13]

On 20 June, Kleber took his two divisions, under Duhesme and Montaigu, to Chapelle-lez-Herlaimont, attacking in four columns and driving the enemy forces in the town out, before returning to their defensive positions with Montaigu positioned from Trazegnies back to the town of Pieton, and Duhesme on his right, stretching from Trazegnies to the Pieton river.[citation needed]

On 21 June, Championnet and Morlot attacked Quatre-Bras and drove away the Allied force at the crossroads, before returning to their entrenchments.[citation needed]

On 22 June, Kleber attacked Chapelle-lez-Herlaimont again with his two divisions to drive out the Allies, who had returned.[citation needed]

The surrender of Charleroi

[edit]At 7 am on 25 June, seeing that no relief appeared to be forthcoming after a week and that the French were about to begin their third parallel (a trench line close enough to launch infantry assaults from), Reynac asked for terms of surrender.[14]

When presented with Reynac's request for terms by a major from his staff, it was refused by the Representative of the People Louis-Antoine Saint-Just, who was in charge of negotiations. Saint-Just demanded an immediate surrender instead. Armand de Marescot, the chief engineer of the forces on the Sambre at this time, was present at the negotiations and recorded the following exchange in his campaign report:

SAINT-JUST: I don't want this piece of paper (i.e. Reynac's note with proposed terms of surrender), I want the place itself.

MAJOR: But if we surrender at discretion (i.e.unconditionally), we will be dishonoured.

SAINT-JUST: We can neither honour or dishonour you, just as it is not in your power to honour or dishonour the French nation. There is no connection between you and us.

MAJOR: But can we not obtain some form of capitulation (i.e. terms)?

SAINT-JUST: Yesterday we could have listened to you; today you must surrender at discretion. I have spoken; I have used the powers entrusted to me; I will take back nothing. I count on the courage of the army, and mine.[15]

Saint-Just's threat was just a bluff; the French were not actually ready to assault Charleroi. It would have taken at least another eight days for the French to have taken the fortress by assault if resistance had continued under a resolute commander.[16] However, Saint-Just needed to intimidate Reynac into surrendering as soon as possible because the French had been aware for some days that the Allied main army was already nearby and their attack to relieve Charleroi was imminent.[citation needed]

In fact, the Allies were already getting dangerously close; on 25 June itself, as Reynac was negotiating his surrender, a detachment from Coburg's army was already trying to get to the ridge of Heppignies to fire rockets, an agreed-upon signal that the relief army had arrived. However, they were driven away by Championnet, whose division occupied the ridge, before they could get close. They were only able to launch their rockets from Frasne (modern Frasnes-lez-Gosselies), too far away to the north to be seen.[17] Around midnight on the day of the battle, an Austrian cavalry officer, Count Radetzky, did manage to infiltrate the French lines and actually reach the walls of Charleroi to discover it was already captured, but was then injured and chased by a French patrol on the way back later in the morning, and did not make it back to headquarters with his news until the afternoon, when the battle was already in full swing.[18]

Despite the fact that the French were clearly not ready to assault the fortress yet, Reynac had been discouraged by the apparent lack of any relief, and was intimidated by Saint-Just's posturing and threats. Seeing no point in further resistance, he agreed to surrender unconditionally that very afternoon. Forces from Hatry's division, which had been besieging Charleroi, then marched in to take possession of the city.[19]

Reynac's surrender had come in the nick of time for the French. The very next morning, the Allies would commence the battle of Fleurus to relieve Charleroi–just half a day too late. Hatry's division, freed up from siege duties, would make an important contribution as a reserve force during the battle.[citation needed]

Prelude to battle

[edit]Coburg seeks decisive battle at Charleroi

[edit]The campaigns on the Sambre were only half of the strategy of General Charles Pichegru, who was the commander in chief of the entire front in the Low Countries, which at the time included the Army of the North, and also the Army of the Ardennes. As the Sambre forces attacked from Pichegru's right wing, his left had defeated the Allies in several battles around Courtrai, and had laid siege to Ypres since 1 June.[citation needed]

With the French defeat at the battle of Lambusart on 16 June, Coburg had assumed the danger from that wing was now over, and he felt free to relieve the siege of Ypres on the other wing by reinforcing Count Clerfayt, who was commanding the Austrian forces trying to relieve Ypres.[citation needed]

Marching with 23 battalions of infantry and 30 squadrons of cavalry on 18 June, however, Coburg had only just arrived at Coeyghem (modern Kooigem) later that day when he received the news that Ypres had surrendered and Jourdan had recrossed the Sambre, both on that same day.[20]

With no siege to relieve, but also freed of the immediate need to fight on two fronts, Coburg returned to Tournai, where he opted to seek a decisive battle on the Sambre by uniting the Allied main army, now freed up, with Orange's forces for an all-out attack on the French on the Sambre wing.[citation needed]

Securing the Duke of York's cooperation

[edit]Coburg planned to bring the 12,000 Austrians under his command at Tournai towards Charleroi to join with Orange's and Beaulieu's 40,000 in the theatre for the decisive battle against Jourdan.[21] However, the concentration of Austrian forces on the left wing for a decisive battle created two complications:

- It also meant denuding the wing that was defending the Scheldt on the Allied right wing, leaving only the forces in English pay, under the Duke of York, as well as Clerfayt’s corps, to hold the river and cover Brussels. These would be severely outnumbered by the French forces facing them.[citation needed]

- Under their standing orders, the departure of these Austrians to the east could be construed by the British and British-paid troops as a ruse to cover the abandonment of the Low Countries, and would lead to them immediately withdrawing to protect their allies in Holland and the Netherlands, as they were unwilling and unable to fight alone to defend Austrian interests if the Austrians themselves had withdrawn their forces.[citation needed]

Coburg needed to convince the Duke of York to take command of the forces around Tournai for a few weeks, guard the line of the Scheldt against Pichegru, and delay his withdrawal to the Netherlands.[citation needed]

However, this at first met with refusal, as the English suspected that the Austrians were trying to use them to cover a retreat from the Low Countries. This was exacerbated by a letter which Orange had sent to the high command at Tournai, in which he assessed that Kleber’s attack on his forces at Chapelle-lez-Herlaimont on 20 June was probably intended to cover a retreat, proven by the fact that he was able to reoccupy the town on the 21st with no resistance.[citation needed]

The impression given by Orange that the Sambre front was no cause for concern initially confirmed York’s suspicions that Coburg’s was using the Sambre as an excuse to begin an Austrian withdrawal towards the Meuse and out of the Low Countries. However, after a further exchange of letters in which Coburg clarified that Orange was mistaken and clarified that the situation was truly urgent, York finally agreed to take command on the Scheldt, but only on condition that a garrison of Austrians remain to defend Tournai, the main Allied base, because York's force was too weak to defend both the river and the town.[22]

York also offered to bring his corps of British-paid troops to join in the relief of Charleroi, on the basis that this concentration would give Coburg even greater numbers to secure a strong victory that would free him up to then attack the other wing. He also argued that if Coburg was defeated, York would not be able to hold the Scheldt alone anyway, so he might as well join in the attack on the Sambre.[23] However, Coburg declined this offer, preferring to leave York on the Scheldt with the Austrian garrison he requested.[citation needed]

The two generals also agreed that York could commence a retreat to Holland if Coburg was defeated on the Sambre. York then positioned his troops between Tournai and Oudenaarde to guard the river while still affording them a good route of retreat to Holland if needed.[22]

Opposing forces

[edit]Coburg marches to Charleroi

[edit]

After getting York's agreement and arranging for the army's stores to be moved rearward from Tournai to Brussels and Antwerp in case of defeat, Coburg commenced a forced march with his 12,000 men in 13 battalions and 26 squadrons.[24] Setting out from Tournai on 21 June, he reached Ath by the end of the day, Soignies at the end of the 22nd, and Nivelles at the end of the 23rd. These marches were conducted in blazing heat, which left the troops exhausted and in need of rest.[citation needed]

Coburg's arrival brought the total Allied forces available to relieve the siege of Charleroi to 52,000:[citation needed]

- Coburg's 12,000 from Tournai, at Nivelles

- Orange's 28,000 between Rouveroy and Bray, with detachments under Nesslinger towards Seneffe and Spiegel towards Quatre-Bras

- 4,000 men under Prince Frederick of Orange near Croix

- 8,000 men under Beaulieu near Gembloux

Coburg decided to give battle on 26 June after resting his men and reconnoitering the situation.[citation needed]

French preparations

[edit]

Jourdan quickly detected Coburg's arrival, but overestimated that the Allied forces numbered 70,000, on par with his strength. As a result, Jourdan opted to act defensively, receiving the imminent Allied attack from within his fortifications. To prevent Allied penetrations from destabilising his entire line like at the battle of Lambusart, he pulled Duhesme's division of Kleber's corps back from the Pieton river to Jumet to act as a reserve on the left, while positioning Hatry to the east of Ransart as a reserve for the right.[citation needed]

During this period, Jourdan also sought to call in Muller's and Scherer's divisions, guarding the right bank of the Sambre further west, to reinforce his army, but he was not given authority over them by the Committee of Public Safety. Jourdan then contacted General Ferrand, the garrison commander of Maubeuge further to the west, and requested any troops he could spare from the division-sized garrison. Ferrand sent the 6,000 men of Daurier's brigade to Jourdan, who took position at Leernes, beyond the heights of l’Espinette, with a vanguard at Fontaine l’Eveque.[citation needed]

While reserves were now available, Jourdan's left wing was now considerably weakened, consisting solely of Montaigu's now-overstretched division, pushed far forward to Trazegnies-Miaucourt (within modern Courcelles), and Daurier's brigade.[citation needed]

Despite this weakness, Jourdan opted to keep Montaigu far forward in this vulnerable position as he wanted maximum time and space to protect both the pontoon bridges on the Sambre near Marchienne-au-Pont which the army depended on for retreat, as well as the reserve artillery at Montigny-sur-Tilleul, which he had not yet had time to bring into Charleroi.[25]

To minimise Montaigu's losses, he instructed the division commander to slowly give ground if enemy pressure grew too great, withdrawing on Marchienne-au-Pont. Daurier's brigade meanwhile would conduct a fighting withdrawal if needed to defend heights of l’Espinette, within artillery range of the crossings at Marchienne-au-Pont, to prevent the enemy from occupying it and interdicting the army's route of retreat.[citation needed]

French strength

[edit]The French army's paper strength on the eve of battle consisted of:[citation needed]

- The divisions of Hatry, Morlot, Lefebvre and Championnet of the Army of the Moselle (42,000 men)

- The divisions of Duhesme and Montaigu under Kleber, of the Army of the North (18,000 men)

- The Army of the Ardennes, made up of the divisions of Marceau and Mayer, minus detachments to Dinant, under overall command of Marceau (11,500 men)

- Daurier’s brigade (6,000 men)

- Dubois’ cavalry division (2,300 men)

Subtracting 3,000 men as casualties from the battle of Lambusart, and 2,000 men assigned to garrison Charleroi, this left Jourdan some 75,000 men available for battle.[26]

Allied attack plans

[edit]

Coburg, with his headquarters at Nivelles, planned two major attacks. Like at Lambusart, his main blow was to be at the French right flank, which he hoped to break to get behind the French centre and envelop them. This would be accompanied by an attack on the French left, divided from the rest of the army by the river Pieton, intended to capture the river crossings the French needed to retreat, making doubly sure they would be trapped on the left bank of the Sambre. They would be supported with attacks in the centre delivered by smaller columns.[citation needed]

Coburg divided his attack force into five columns, positioned from east to west as follows:[27]

Archduke Charles' and Beaulieu's columns

[edit]Consisting of 20 battalions of infantry, 36 squadrons of cavalry, and 36 guns, these were to be the main attack force, and were placed under the overall command of Archduke Charles, the brother of the Austrian emperor. Their mission was to crumple the French right. The combined force was to march at 2 am on the 26th from the tavern of Point-du-Jour (at the modern intersection of the N29 and N93) to near Gros-Buisson (the plain north of Fleurus),[9] where they would split into two columns:[citation needed]

- General Johann Peter Beaulieu’s column, with 13 battalions, 20 squadrons and 18 guns, would turn south just before reaching Fleurus, and attack Lambusart, Baulet and Wanfersee, before turning parallel to the Sambre, outflanking the entire line, and getting into the rear of Jourdan's army

- Charles’ own column, with 7 battalions, 16 squadrons and 18 guns, would march through Fleurus and attack the tavern of Campinaire.

Prince Kaunitz's column

[edit]Consisting of 8 battalions of infantry, 18 squadrons of cavalry and 17 guns, the column under Wenzel Anton, Prince of Kaunitz-Rietberg, was to march from the tree of Bruyere (which still stands today at the southern tip of the La Bruyere golf course), where he was encamped, to the village of Chassart[9] to spend the night of the 25th, then march towards Fleurus and attack Heppignies and Wagnee once Charles’ column had engaged at Campinaire.

Quosdanovich's column

[edit]Consisting of 7 battalions, 16 squadrons and 16 guns, Peter Vitus von Quosdanovich’s column was to move from Nivelles, where it was located, to Grand-Champ, the plain north of the village of Mellet, on the night of the 25th. It was then to wait for Kaunitz's column to reach the forest of Lombue (modern Domaine du Bois-Lombut)[7] at daybreak on the 26th before moving on Gosselies, via Pont-a-Migneloup (modern Pont-a-Mignetoux), Mellet and the forest of Lombue, attacking together with Kaunitz.

The Prince of Orange's column

[edit]Based at Chapelle-lez-Herlaimont at 2 am on 26 June with 24 battalions, 32 squadrons and 22 guns, Orange's column was generally to capture Courcelles and Forchies-la-Marche, then capture the forest of Moncaux (the modern Charleroi suburb of Monceau-sur-Sambre),[7] the heights of l’Espinette, and the Sambre crossing at Landelies.

Orange intended to split his column into three:

- One sub-column under Christian August, Prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont, would attack from Trazegnies and Forchies towards Marchienne-au-Pont

- Another sub-column, under his son Prince Frederic of Orange, was to capture Anderlues and Fontaine l’Eveque, the heights of l’Espinette, then cross the Sambre at Rus and converge on Marchienne-au-Pont

- The third sub-column under General Riese was to march between Waldeck and Frederic to keep them in communication and reinforce either column as needed

Battle

[edit]

The battle of Fleurus was tactically indecisive, with the French successfully holding the line despite intense fighting, and counterattacking against the Allies in the afternoon despite initial defeats on both their flanks in the morning.

At some point in the afternoon, Count Radetzky, who had discovered that Charleroi had been captured, finally made it back to report to Coburg. With no siege to relieve, and with the inconclusive fighting and the strength of the French defences and numbers, Coburg decided further attack was not worth the potential gain, and ordered a withdrawal around 3 pm.

Archduke Charles' attack

[edit]On the French right, Lefebvre's division had moved forward from its fortifications at Campinaire and occupied an advance position at Fleurus before the 26th. Charles’ advance towards Fleurus brought his column into contact with Lefebvre, and fighting commenced beyond and in the town between 5.30 and 6 am.[28]

Meanwhile, at around the same time, Beaulieu's column attacked Marceau's division at Baulet and Velaine, pushing them back into the forest of Gopiaux between 9 and 9.30 am. These held until 10.30 am, when the capture of an important strongpoint broke this line, causing this part of Marceau's forces to flee towards the Sambre crossings at Tamines and Tergnee.[28]

Beaulieu immediately marched towards Marceau's entrenched camp at Baratre, 800m east of Lambusart. Although Marceau's main force was located here, panic from the defeat of his vanguard had spread and many of the soldiers fled without offering much resistance, and despite Marceau's best efforts to rally them. Beaulieu subsequently captured Baratre with ease, and continued his advance on Lambusart.[28]

Marceau's withdrawal into Gopiaux and Baratre had uncovered Lefebvre's right flank, and Lefebvre ordered a retreat around 9.30 am from Fleurus to his main line of French fortifications at Campinaire and Lambusart. Once there, Lefebvre sent Colonel Jean-de-Dieu Soult, his chief of staff, to check on Marceau and report on the situation on his right. After Soult reported on the capture of Baratre, Lefebvre sent forces east to Lambusart to plug the gap there. Marceau, who managed to rally some of his forces around 12 pm, later returned and joined these units in the defence of the town.[28]

Seizing Fleurus at 10 am, Charles arrived in front of Campinaire just as Beaulieu captured Baratre and reached Lambusart. They launched relentless combined assaults against the French line throughout the afternoon, but the terrain greatly favoured the defenders, and the Allies made no progress apart from capturing a toehold in Lambusart itself. Between 4 and 5 pm, Charles and Beaulieu received Coburg's orders calling off the attack.[28]

The columns began to disengage at around 5 pm, but for Beaulieu, who was attempting to retreat to Gembloux, this coincided with a counterattack on his left flank, launched by Lefebvre, Marceau and reinforcements from Hatry sent by Jourdan. Beaulieu's cavalry rearguard was routed by Lefebvre, although Beaulieu's main force got away. By 6 pm, the Allies on this part of the front had vacated the field.[28]

Orange's attack

[edit]On the French left, the prince of Orange commenced his advance at 1.30 am on the morning of the 26th.[29]

Waldeck's column crossed the Pieton near Mont-A-Gouy (modern Gouy-lez-Pieton),[7] and advanced on Trazegnies, where he clashed with Montaigu, who retreated back across the Sambre by 9 am to defend Marchienne-au-Pont, harried by Waldeck's forces, who occupied the forest of Moncaux behind them.[29]

Meanwhile, Frederic's column had encountered almost no resistance on its advance from Chapelle-lez-Herlaimont, capturing Anderlues and Fontaine l’Eveque and the castle of Wespes[30] before finally being stopped at the heights of l’Espinette by Daurier's brigade, also between 9 and 10 am.

When Orange's forces attacked Montaigu, Kleber had immediately despatched 3 battalions and 3 guns from Duhesme's division in reserve to support Montaigu, but these arrived too late to help. With Montaigu in full retreat, these forces withdrew back to Kleber at the Pieton.[29]

At around 8 am, Kleber decided to secure the bridges across the Pieton with General of Brigade Jean Bernadotte’s brigade of Duhesme's division to create a new refused French left flank after Montaigu's retreat. Later in the morning, with Montaigu holding the Sambre against Waldeck and Daurier holding l'Espinette against Frederic, Kleber decided to counterattack with Duhesme's reserve division in 3 columns.[29]

On the left, Kleber personally took command of one column against the forest of Moncaux. In the centre, Bernadotte would advance west from the bridge at Roux, and Duhesme would advance on the right against Courcelles and Trazegnies.[29]

Beginning their advance between 11 am and noon, the columns of Duhesme's division pinned down Waldeck's forces throughout the afternoon, finally forcing him back to Forchies-la-Marche at 5 pm.[29]

Meanwhile, Prince Frederic's column had been pushing hard against Daurier, and by noon, was threatening to capture the bridges further west at d’Aulnes and Lobbes, from which he could cross and cut off Daurier's retreat at Landelies. It was at this moment that Poncet's brigade of Montaigu's division, having retreated back across the Sambre at Rus and Marchienne-au-Pont, was ordered to recross and counterattack Frederic at Aulnes to support Daurier's defence.[29]

Poncet's brigade counterattacked in the early afternoon, and, combined with Daurier, drove Frederic back to the heights of Anderlues by 3 pm.[29]

At this point, Orange, seeing that the French still stood strong and were even reinforcing their left, and concerned that he was too far forward to be supported by the next column on his left under Quosdanovich, decided to withdraw at around 5 pm to Haine-Saint-Paul. Coburg's orders for a general withdrawal arrived soon after Orange had commenced his own withdrawal.

Kaunitz's attack

[edit]Opposite the French centre, Kaunitz's column had been ordered to attack once he heard Archduke Charles’ column commence fighting. At 5.30 am, hearing Charles’ and Lefebvre's guns, Kaunitz ordered his column forward to capture Heppignies.[31]

Championnet's division was defending this section of the front, and had been standing to since 2 am in preparation for Kaunitz's attack, after Championnet spotted Kaunitz moving into his attack position near the tree of Bruyere the previous evening. Thus, when Kaunitz ran into one of Championnet's advanced brigades under General Grenier near Chassart to the north, they were ready, and conducted a fighting withdrawal into Saint-Fiacre, which had been fortified beforehand.[31]

The brigade at Saint-Fiacre held until 9.30 am, when Lefebvre's division evacuated Fleurus and fell back on Campinaire. Championnet then ordered Saint-Fiacre's evacuation to the main line of fortifications on the heights of Heppignies. This evacuation opened a gap in the French lines as Wagnee, between Championnet and Lefebvre, was only held one battalion of Championnet's division. Jourdan then sent a half-brigade from Hatry's division to reinforce the defenders of Wagnee.[31]

Kaunitz attempted to advance on Championnet's entrenchments, but the terrain in front of Championnet's division strongly favoured the defensive. Kaunitz himself had also not committed to a full attack as he did not want to advance too quickly, because the cordon system of war, then prevalent, dictated that columns had to advance in line with each other to exert equal pressure on the enemy front, and Archduke Charles’ column, whom he was to take his cue from, had at the time been checked by Lefebvre's defence.[31]

However, although he was holding well against Kaunitz's attacks, at 11 am things changed. Championnet heard that Kleber's left wing (actually only Montaigu's division) had retreated all the way to Marchienne-au-Pont, and that Lefebvre now had to cover Marceau's front as well as his own after Marceau's corps broke. With Archduke Charles and Beaulieu resuming their advance on Lambusart, Kaunitz now also resolutely took the offensive and pushed Championnet hard, while an Allied detachment worked its way into the northwest sector of Heppignies, on Championnet's flank, via a sheltered defile.[31]

The combination of these factors with the failure of a counterattack at 2 pm by one of Championnet's brigades and d'Hautpoul's brigade of cavalry, and the inability of Championnet's messengers to find, reach, and report on the true situation of Lefebvre's division, led Championnet to believe the worst. He requested permission from Jourdan to withdraw from what he thought was an exposed position, and, with the permission granted, began retreating from Heppignies at 3.30 pm.[31]

However, just as the division was descending the rear slopes of Heppignies ridge, news arrived from Jourdan that Lefebvre had stopped Charles and Beaulieu and reinforcements from Hatry's division were coming up. With his division/s right flank safe, Championnet was ordered to counterattack Kaunitz with his division, Dubois’ cavalry from the 2 pm attack, and Hatry's reinforcements.[31]

Launching a bayonet charge at 4 pm, Championnet's infantry and Dubois’ cavalry surprised Kaunitz's forces, who were forming up for pursuit. Dismayed at the revival of an enemy they had thought was beaten, and caught in disorder just as they were redeploying into columns of pursuit, Kaunitz's column broke and fled the battlefield within the hour. Having also received Coburg's order to withdraw at about this time, Kaunitz made no effort to renew the fight, and withdrew his remaining forces.[31]

Quosdanovich's attack

[edit]Opposite the French left centre, Quosdanovich's column marched from Nivelles on the evening of 25 June, passed through Quatre-Bras in the night, and seized Frasne at daybreak on the 26th from a detachment of Morlot's division.[32]

Advancing through Frasne, Quosdanovich deployed his column at 4 am on the Grandchamp, a plain that lay between Frasne and Mellet. However, units of Dubois’ cavalry division, in their element on the open plain, managed to delay Quosdanovich for 3 hours while Morlot deployed his division behind them, around the village of Mellet.[32]

Morlot then attacked on Quosdanovich's front as well as on his right flank via Thumeon. The fighting continued until Morlot's right was uncovered by Grenier's withdrawal from Chassart to Saint-Fiacre. This, coupled with a successful counterattack by Quosdanovich against Morlot's flanking force at Thumeon, forced the French general to withdraw to the south bank of the stream running through Pont-a-Migneloup.[32]

Quosdanovich's artillery then pinned Morlot's division down under heavy fire until about 3 pm, with neither side able to advance. At 3 in the afternoon, Morlot received orders from Jourdan to withdraw to Gosselies, in conjunction with Championnet's withdrawal. Quosdanovich was unable to pursue, as the French had broken the bridge at Pont-a-Migneloup and he had to call up his pontoon train to bridge the stream before he could resume his advance.[32]

The artillery engagement at Pont-a-Migneloup was the last engagement on this sector of the front. Just after 4 pm, before he was able to cross and engage Morlot again, Quosdanovich received Coburg's order to withdraw, and immediately complied.[32]

French observation balloon

[edit]

The battle of Fleurus was the first battle in history that incorporated aerial reconnaissance and observation of an enemy force. This was provided by a French reconnaissance balloon, l'Entreprenant, operated by a crew under Captain Coutelle of the Aerostatic Corps, which continuously informed Jourdan of Austrian movements.

During the battle, l’Entreprenant was deployed on the 190-metre (620 ft) tall hill where the Jumet windmill was located (modern Bellevue, a Charleroi suburb),[7] as it was the highest location in the area. For much of the morning, Jourdan based himself on the hill to receive and better understand the reports from the aeronauts in real time. Representative of the People Guyton, one of the three attached to Jourdan's army, also mentioned in his reports to the Committee of Public Safety that Morlot, whose headquarters was located in Gosselies, spent two hours airborne in the balloon in the morning observing the enemy.[33]

Despite the presence of the balloon, its intelligence value was questionable due to its altitude limitations and instability as a platform, and it apparently had no appreciable influence over the course of the battle. Soult, in his memoirs written after the fall of Napoleon, declared that the balloon was useless:

“I will not say anything about the balloon that we put up during the battle over the heads of the combatants, and this ridiculous innovation would not even deserve to be mentioned, if it hadn’t been made out to be something important. The truth is, this balloon was just plain embarrassing...At the beginning of the action, a general and an engineer entered the gondola to observe, it was said, the enemy movements…but at the height where we let them go up, the details escaped their view and everything was confused. We were no better informed, and no one paid any attention to it, neither the enemy nor ourselves.”[34]

Championnet likewise said in his memoirs about the balloon that "nothing of importance came from this post."[35]

Most tellingly, on 3 Pluviose Year VII (22 January 1799), Jourdan recommended in a letter to Barthelemy Scherer, who was Minister of War at the time, that "aerostats (balloons) are not necessary for the army, unless some other way of using them is found." Despite being with the balloon for most of the morning of the battle, Jourdan also made no mention of it, or its usefulness, at all in his memoirs.

Aftermath

[edit]The battle of Fleurus had been intense and unrelenting, and both French and Allied armies were exhausted by the fighting. Indeed, Soult wrote that it was "fifteen hours of the most desperate fighting I ever saw in my life."[36] The French did not pursue the retreating Allied army in any way, and made no movements for two days to rest. The Allies, meanwhile, retreated to Braine l’Alleud and Waterloo.

It is generally agreed that the battle was a costly one for the French, with casualties estimated between five and six thousand. The Allied losses have always been in dispute: the French claimed significantly higher losses than their own, while the Allies claimed far less. Traditional estimates attribute "considerable casualties" to Coburg's army,[37] and hover near five thousand Allied killed and wounded.[5][38][39] However, according to historian Digby Smith (1998), Austrian-Dutch losses numbered 208 killed, 1,017 wounded, and 361 captured. In addition, the French captured one mortar, three caissons, and one standard, while the Austrians captured one cannon and one standard.[40]

While tactically indecisive, Fleurus was the strategically the decisive battle of the French campaign of 1794 in the Low Countries, after which the Austrians gave up on contesting the Low Countries, and left it to the French. Smith (1998) wrote:

By this stage of the war the court in Vienna was convinced that it was no longer worth the effort to try to hold on to the Austrian Netherlands and it is suspected that Coburg gave up the chance of a victory here so as to be able to pull out eastwards.[4]

After Fleurus, Jourdan's force was formally consolidated as the Army of Sambre and Meuse, and given the mission of capturing the eastern Low Countries and going after Coburg's army. Just a month after Fleurus, Jourdan had occupied Mechelen and Louvain (15 July), Namur (17 July) and Liege (27 July), while Pichegru had entered Brussels (11 July) and captured Antwerp (27 July).

Unable and unwilling to contest the French advance further, and threatened with destruction by the combined pressure from Pichegru's and Jourdan's armies acting in concert (which did not happen only because the Committee of Public Safety diverted Pichegru's forces elsewhere at the crucial time), Coburg began a retreat eastward to the Meuse on 15 July, and crossed the river at Maastricht, the eastern border of the Low Countries, into Germany on the 24th. The main battlefields of the war against Austria would now shift from Belgium to Germany and the Rhine.

The Austrian defeat at Fleurus also led to the breakup of the Allied army in the north as the Austrian abandonment of the Low Countries also led to the withdrawal of English and Dutch forces northwards, away from the Austrians, to defend the Netherlands. The Duke of York's forces crossed into the Netherlands at Roosendaal on 24 July, the same day Coburg crossed the Meuse at Maastricht, leaving the Low Countries completely vacated. Divided and outnumbered, the English and Dutch were incapable of holding back the French on their own, and, overturned by the Batavian revolution in Amsterdam on 18 January 1795, the Dutch Republic was extinguished and replaced by the pro-French Batavian Republic instead.

Politically, the battle invalidated the argument that continuation of the revolutionary Reign of Terror was necessary because of the military threat to France's very existence. Thus, some would argue, victory at Fleurus was a leading cause of the Thermidorian Reaction a month later. Saint-Just arrived in Paris after such a great victory only to die with Maximilien Robespierre and the other leading Jacobins.

References

[edit]- ^ A Short History of France. Taylor & Francis. p. 147. GGKEY:W8BKL8DP129. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ^ Origins of Political Extremism: Mass Violence in the Twentieth Century and Beyond. Cambridge University Press. 2011. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-139-50077-7. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ Smith 1998, p. 86.

- ^ a b Smith 1998, p. 87.

- ^ a b Rothenberg 1980, p. 247.

- ^ Dupuis 1907, pp. 303–305.

- ^ a b c d e f KBR: The Royal Library of Belgium (1770–1778). "The Ferraris Map". p. 81: Charleroi. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ a b c KBR: The Royal Library of Belgium (1770–1778). "The Ferraris Map". p. 98: Fleuru. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ a b c KBR: The Royal Library of Belgium (1770–1778). "The Ferraris Map". p. 97: Gembloux. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ KBR: The Royal Library of Belgium (1770–1778). "The Ferraris Map". p. 66: Merbes le Chateau. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ Dupuis 1907, p. 305.

- ^ Dupuis 1907, pp. 308, 320.

- ^ Dupuis 1907, pp. 311–313.

- ^ Dupuis 1907, p. 309.

- ^ Marescot, Armand Samuel de (1795). Relation des trois attaques de la place de Charleroy. Vol. B1 34. Vincennes: Archives du Service Historique de l'Armee.

- ^ Dupuis 1907, p. 322.

- ^ Dupuis 1907, p. 320.

- ^ Dupuis 1907, p. 321.

- ^ Dupuis 1907, p. 311.

- ^ Dupuis 1907, p. 314.

- ^ Dupuis 1907, p. 315.

- ^ a b Dupuis 1907, pp. 316–319.

- ^ Fortescue, Sir John William (1918). British Campaigns in Flanders, 1690–1794. Vol. 4. London: Macmillan. p. 354.

- ^ Dupuis 1907, p. 319.

- ^ Dupuis 1907, p. 324.

- ^ Dupuis 1907, p. 323.

- ^ Dupuis 1907, pp. 327–332.

- ^ a b c d e f Dupuis 1907, pp. 357–360.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dupuis 1907, pp. 336–342.

- ^ KBR: The Royal Library of Belgium (1770–1778). "The Ferraris Map". p. 82: Thuin. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dupuis 1907, pp. 345–357.

- ^ a b c d e Dupuis 1907, p. 344.

- ^ Dupuis 1907, p. 377.

- ^ Soult, Jean-de-Dieu (1854). Memoires du Marechal Soult, Duc de Dalmatie (in French). Vol. 1. Paris: Librairie Amyot. p. 171.

- ^ Championnet, Jean-Etienne; Faure, Maurice (1904). Souvenirs du General Championnet (in French). Paris: Flammarion. p. 75.

- ^ Glover 1987, p. 162.

- ^ Chandler 1973, p. 169.

- ^ Dodge 1904, p. 114.

- ^ Jobson 1841, p. 312.

- ^ Smith 1998, pp. 86–87.

Bibliography

[edit]- Chandler, David G. (1973). The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-02-523660-8. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Dodge, Theodore Ayrault (1904). Napoleon; a History of the Art of War. Boston; New York: Houghton, Mifflin and company. p. 114. OCLC 1906371. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Dupuis, Victor César Eugène (1907). Les opérations militaires sur la Sambre en 1794: Bataille de Fleurus (in French). Paris: R Chapelot et Cie.

- Glover, Michael (1987). "Jourdan: The True Patriot". In Chandler, David G. (ed.). Napoleon's Marshals. New York: Macmillan Pub Co. pp. 156–175. ISBN 9780029059302. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- Jobson, David Wemyss (1841). History of the French revolution till the death of Robespierre. London: Sherwood & Co. p. 312. OCLC 23929885. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- Rothenberg, Gunther E. (1980). The Art of Warfare in the Age of Napoleon. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-31076-8.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Greenhill Napoleonic Wars Data Book: Actions and Losses in Personnel, Colours, Standards and Artillery, 1792–1815. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

External links

[edit]- U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission: "Military Use of Balloons During the Napoleonic Era". Accessed April 1, 2007.

Media related to Battle of Fleurus (1794) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Fleurus (1794) at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Battle of Tournay (1794) |

French Revolution: Revolutionary campaigns Battle of Fleurus (1794) |

Succeeded by Chouannerie |