Thomas Peel

Thomas Peel | |

|---|---|

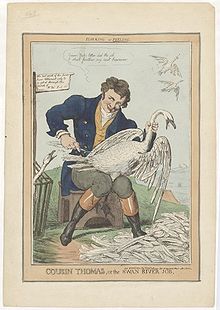

No photograph or portrait of Thomas Peel is known to exist. This is a contemporary caricature. | |

| Born | 1793 Lancashire, England |

| Died | 22 December 1865 Mandurah, Western Australia |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Harrow School |

| Occupation | Settler |

| Relatives | Sir Robert Peel (second cousin) |

Thomas Peel (1793 – 22 December 1865)[1] organised and led a consortium of the first British settlers to Western Australia. He was a leader of the colonial militia that participated in Pinjarra massacre in 1834, which saw 70-80 of the Aboriginal Binjareb people killed.[2] He was a second cousin of two-times British Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel.

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Thomas Peel was born in Lancashire, England, the second son of Thomas Peel and his wife Dorothy, née Bolton.[1] He was educated at Harrow School and was employed by attorneys.

Adult life in Australia

[edit]In 1828, he went to London with plans to migrate to New South Wales. However, Peel and three others including an MP, Potter McQueen, formed a consortium to found a colony at the Swan River in Western Australia by sending settlers there with stock and necessary materials. The consortium requested a grant from the British Colonial Office in London of 4,000,000 acres (16,000 km²). The government declined this and offered a grant of 1,000,000 acres (4,000 km²) on certain conditions.

Early in 1829, all the members of the consortium withdrew except Peel. Fresh conditions were made, the final arrangement being that if Peel landed 400 settlers before 1 November 1829, he would receive 250,000 acres (1,000 km²), constituting a block extending to the south east from the south bank of the entire Swan River.[1]: 219 If the conditions were fulfilled, Peel would receive further grants. Solomon Levey was a silent partner.[1]

To deliver the 400 settlers Peel chartered three vessels, Gilmore, Hooghly, and Rockingham. Gilmore, the first to leave, sailed from St Katherine Docks in July 1829 with Thomas Peel and 182 settlers in all.

Gilmore arrived in the Swan River Colony (later expanded and renamed Western Australia) on 15 December, around six weeks later than the government had stipulated. As he had not fulfilled the conditions, the agreed land was no longer reserved for him. On arrival, his settlers established a base ln the beach near Woodman's Point, 13 miles from Fremantle, which Peel called Clarence, after the Duke of Clarence, the heir apparent.[1]: 75 Stores and stock, which were to be sent from Sydney by Cooper & Levey did not arrive.[1]

Hooghly (173 passengers), arrived at Clarence on 13 February 1830. Rockingham (180 passengers), arrived in mid-May 1830. She was wrecked shortly after landing her passengers, but all survived, though supplies were lost.

The settlers stayed at Clarence about a year and then built boats to enable them to go to Perth.

The land eventually granted to him, 250,000 acres (1,000 km²), extended from Cockburn Sound to the Murray River. This settlement, referred to as the Peel Estate, struggled due to lack of labour and limited good-quality farming land. One of the things he tried on the coast was whaling. Peel's poor organising skills, meant that he was soon in difficulties. Within less than two years, he had spent between £20,000 and £50,000 and most of his settlers deserted him.[1] Eventually Peel discharged all but a few from their indentures. In September 1834, Peel was granted further land, but he had little success in developing it. Peel became a member of the Western Australian Legislative Council, but resigned fourteen months later.[1] Some other pioneers (like James Henty) moved to Tasmania and the Port Phillip district.

Peel died on 22 December 1865 at age 72. He was buried in the churchyard in Mandurah.

Pinjarra massacre

[edit]In October 1834, Peel was a part of the British colonial militia, which included Governor James Stirling and John Septimus Roe, involved in the Pinjarra Massacre. It resulted in the murder of 70 to 80 Binjareb people.[2] Peel participated so that he could attract settlers to his land at Mandurah and to take revenge for the killing of his servant Hugh Nesbitt. In later years, he pejoratively described the local Binjareb people as a "nest of hornets".[citation needed]

In 2017, a campaign was started to rename the Peel region because of its ties to Peel, in part as a means to come to terms with the past. The MLA for Murray-Wellington Robyn Clarke supported the project but Premier Mark McGowan dismissed the idea of a renaming.[3][4]

Legacy and cultural references

[edit]Karl Marx referred to Peel in his analysis of capitalism, in a passage where he criticised colonist Edward Gibbon Wakefield:[5]

Mr. Peel, he moans, took with him from England to Swan River, West Australia, means of subsistence and of production to the amount of £50,000. Mr. Peel had the foresight to bring with him, besides, 3000[sic] persons of the working-class, men, women, and children. Once arrived at his destination, "Mr. Peel was left without a servant to make his bed or fetch him water from the river." Unhappy Mr. Peel who provided for everything except the export of English modes of production to Swan River!

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Alexandra Hasluck, 'Peel, Thomas (1793 - 1865)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol. 2, MUP, 1967, pp 320-322. retrieved 2009-11-04

- ^ a b Bates, Daisy M. (5 August 1926). "Battle of Pinjarra: Causes and consequences". The Western Mail. p. 40. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ "Traditional Owners campaign to rename Peel region". Green Left Weekly. 28 October 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ^ Hondros, Nathan (26 October 2017). "'I'm not into changing the names of regions': Premier rejects Peel name change". WAtoday. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1867). Engels, Frederick (ed.). Das Kapital: Kritik der politischen Ökonomie [Capital: A Critique of Political Economy] (in German). Vol. 1. Translated by Moore, Samuel; Bibbins Aveling, Edward; Untermann, Ernest (4th ed.). New York: The Modern Library. p. 840. OCLC 70747658.

Further reading

[edit]- Appleyard R T and Manford T The Beginning: European discovery and early settlement of Swan River, Western Australia (University of Western Australia Press, Nedlands 1979) ISBN 0-85564-146-0

- Hasluck, Alexandra: Thomas Peel of Swan River (Oxford University Press, Melbourne 1965)

- Hitchcock, JK, 1929, The History of Fremantle, The Front Gate of Australia 1829-1929, Fremantle City Council: pp17,19.

- Serle, Percival (1949). "Peel, Thomas". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus & Robertson.

- Peel Family (timeline) at Mandurah Community Museum

- 1793 births

- 1865 deaths

- Settlers of Western Australia

- Aboriginal genocide perpetrators

- English mass murderers

- Mandurah

- Members of the Western Australian Legislative Council

- 19th-century Australian politicians

- People educated at Harrow School

- English emigrants to colonial Australia

- Australian people in whaling