The Water-Babies

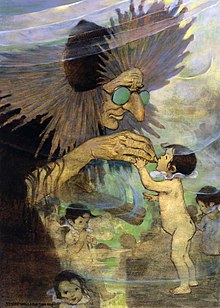

The Water Babies (illustrated by Linley Sambourne), Macmillan & Co., London 1885 | |

| Author | Charles Kingsley |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Satire |

| Published | London: Macmillan, 1863[1] |

| Media type | Book |

The Water-Babies: A Fairy Tale for a Land-Baby is a children's novel by Charles Kingsley.[2] Written in 1862–1863 as a serial for Macmillan's Magazine, it was first published in its entirety in 1863. It was written as part satire in support of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species. The book was extremely popular in the United Kingdom and was a mainstay of British children's literature for many decades.

Story

[edit]The protagonist is Tom, a young chimney sweep, who falls into a river after encountering an upper-class girl named Ellie and being chased out of her house. There he appears to drown and is transformed into a "water-baby",[3] as he is told by a caddisfly – an insect that sheds its skin – and begins his moral education. The story is thematically concerned with Christian redemption, though Kingsley also uses the book to argue that England treats its poor badly, and to question child labour, among other themes.

Tom embarks on a series of adventures and lessons, and enjoys the community of other water-babies on Saint Brendan's Island once he proves himself a moral creature. The major spiritual leaders in his new world are the fairies Mrs. Doasyouwouldbedoneby (a reference to the Golden Rule), Mrs. Bedonebyasyoudid, and Mother Carey. Weekly, Tom is allowed the company of Ellie, who became a water-baby after he did.

Grimes, his old master, drowns as well, and in his final adventure, Tom travels to the end of the world to attempt to help the man where he is being punished for his misdeeds. Tom helps Grimes to find repentance, and Grimes will be given a second chance if he can successfully perform a final penance. By proving his willingness to do things he does not like, if they are the right things to do, Tom earns himself a return to human form, and becomes "a great man of science" who "can plan railways, and steam-engines, and electric telegraphs, and rifled guns, and so forth". He and Ellie are united, although the book states (perhaps jokingly) that they never marry, claiming that in fairy tales, no one beneath the rank of prince and princess ever marries.

The book ends with the caveat that it is only a fairy tale, and the reader is to believe none of it, "even if it is true".

Interpretation

[edit]In the style of Victorian-era novels, The Water-Babies is a didactic moral fable. In it, Kingsley expresses many of the common prejudices of that time period, and the book includes dismissive or insulting references to Americans,[a] Jews,[b] Blacks,[c] and Catholics,[d] particularly the Irish.[f]

The book had been intended in part as a satire, a tract against child labour,[6] as well as a serious critique of the closed-minded approaches of many scientists of the day[7] in their response to Charles Darwin's ideas on evolution, which Kingsley had been one of the first to praise. He had been sent an advance review copy of On the Origin of Species, and wrote in his response of 18 November 1859 (four days before Darwin's book was published) that he had "long since, from watching the crossing of domesticated animals and plants, learnt to disbelieve the dogma of the permanence of species," and had "gradually learnt to see that it is just as noble a conception of Deity, to believe that He created primal forms capable of self development into all forms needful pro tempore and pro loco, as to believe that He required a fresh act of intervention to supply the lacunas which He Himself had made", asking "whether the former be not the loftier thought."[8]

In the book, for example, Kingsley argues that no person is qualified to say that something that they have never seen (like a human soul or a water-baby) does not exist.

"How do you know that? Have you been there to see? And if you had been there to see, and had seen none, that would not prove that there were none ... And no one has a right to say that no water-babies exist, till they have seen no water-babies existing ; which is quite a different thing, mind, from not seeing water-babies... You must not talk about " ain’t ” and " can’t ” when you speak of this great wonderful world round you, of which the wisest man knows only the very smallest corner, and is, as the great Sir Isaac Newton said, only a child picking up pebbles on the shore of a boundless ocean. You must not say that this cannot be, or that that is contrary to nature. You do not know what nature is, or what she can do ; and nobody knows ; not even Sir Roderick Murchison, or Professor Owen, or Professor Sedgwick, or Professor Huxley, or Mr. Darwin, or Professor Faraday, or Mr. Grove."[9]

In his Origin of Species, Darwin mentions that, like many others at the time, he thought that changed habits produce an inherited effect, a concept now known as Lamarckism.[10] In The Water-Babies, Kingsley tells of a group of humans called the Doasyoulikes who are allowed to do "whatever they like" and who gradually lose the power of speech, degenerate into gorillas and are shot by the African explorer du Chaillu. He refers to the movement to end slavery in mentioning that one of the gorillas shot by du Chaillu "remembered that his ancestors had once been men, and tried to say, 'Am I Not A Man And A Brother?', but had forgotten how to use his tongue".[11]

The Water-Babies alludes to debates among biologists of its day, satirising what Kingsley had previously dubbed the "great hippocampus question" as the "great hippopotamus test". At various times the text refers to "Sir Roderick Murchison, Professor (Richard) Owen, Professor (Thomas Henry) Huxley, (and) Mr. Darwin", and thus they become explicitly part of the story. In the accompanying illustrations by Linley Sambourne, Huxley and Owen are caricatured, studying a captured water-baby. In 1892 Thomas Henry Huxley's five-year-old grandson Julian saw this engraving and wrote his grandfather a letter asking:

Dear Grandpater – Have you seen a Waterbaby? Did you put it in a bottle? Did it wonder if it could get out? Could I see it some day? – Your loving Julian.[12]

Huxley wrote back a letter (later evoked by the New York Sun's "Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus" in 1897):

My dear Julian – I could never make sure about that Water Baby.

I have seen Babies in water and Babies in bottles; the Baby in the water was not in a bottle and the Baby in the bottle was not in water. My friend who wrote the story of the Water Baby was a very kind man and very clever. Perhaps he thought I could see as much in the water as he did. – There are some people who see a great deal and some who see very little in the same things.

When you grow up I dare say you will be one of the great-deal seers, and see things more wonderful than the Water Babies where other folks can see nothing.[12]

Environmentalism

[edit]Only where men are wasteful and dirty, and let sewers run into the sea, instead of putting the stuff upon the fields like thrifty reasonable souls ; or throw herrings’ heads, and dead dog-fish, or any other refuse, into the water ; or in any way make a mess upon the clean shore, there the water-babies will not come, sometimes not for hundreds of years (for they cannot abide anything smelly or foul) : but leave the sea-anemones and the crabs to clear away everything, till the good tidy sea has covered up all the dirt in soft mud and clean sand, where the water-babies can plant live cockles and whelks and razor shells and sea-cucumbers and golden-combs, and make a pretty live garden again, after man’s dirt is cleared away. And that, I suppose, is the reason why there are no water-babies at any watering-place which I have ever seen.

Charles Kingsley, The Water-Babies

Literary critic, Naomi Wood, treats Kingsley's "characteristically Victorian naturalism as proto-environmentalism," since it both educates the reader about the environment but also advocates political action to protect the environment.[13] Kingsley is critical of industrial and urban pollution and wastefulness. Catherine Judd points out that the city, the loud coal mining engines, and the stultifying country manor of a British landowner are all contrasted with an Edenic Northern English landscape.[14] With detailed descriptions of native fauna, Kingsley immerses his protagonist into a variety of biodiverse terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems so that readers are drawn to see themselves as part of nature.[13]

Adaptations

[edit]The book was adapted into an animated film The Water Babies in 1978 starring James Mason, Bernard Cribbins and Billie Whitelaw. Though many of the main elements are there, the film's storyline differs substantially from the book's, with a new sub-plot involving Tom saving the Water-Babies from imprisonment by a kingdom of sharks.

It was also adapted into a musical theatre version produced at the Garrick Theatre in London, in 1902. The adaptation was described as a "fairy play", by Rutland Barrington, with music by Frederick Rosse, Albert Fox, and Alfred Cellier.[15] The book was also produced as a play by Jason Carr and Gary Yershon, mounted at the Chichester Festival Theatre in 2003, directed by Jeremy Sams, starring Louise Gold, Joe McGann, Katherine O'Shea, and Neil McDermott.[citation needed]

The story was also adapted into a radio series[16] featuring Timothy West, Julia McKenzie, and Oliver Peace as Tom.

A 2013 update for BBC Radio 4 brought the tale to a newer age, with Tomi having been trafficked from Nigeria as a child labourer.[17]

In 2014 it was adapted into a musical;[18] a shortened version premiered at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 2014,[19] with the full version being produced at the Playhouse Theatre, Cheltenham in 2015 by performing arts students of the University of Gloucestershire. It was performed, again by students, in the same venue in June 2019.[20]

In 2019 the story was adapted into a folk opera performed at The Sydney Fringe[21] Australia from a musical score and libretto composed by musician and librettist Freddie Hill in 1999.[22]

Notes

[edit]- ^ When Tom has "everything that he could want or wish," the reader is warned that sometimes this does bad things to people: "Indeed, it sometimes makes them naughty, as it has made the people in America". Murderous crows that do whatever they like are described as being like "American citizens of the new school".[4]

- ^ Jews are referred to twice in the text, first as archetypal rich people ("as rich as a Jew"), and then as a joking reference to dishonest merchants who sell fake religious icons – "young ladies walk about with lockets of Charles the First's hair (or of somebody else's, when the Jews' genuine stock is used up)".[4]

- ^ The Powwow man is said to have "yelled, shouted, raved, roared, stamped, and danced corrobory like any black fellow," and a seal is described as looking like a "fat old greasy negro".[4]

- ^ "Popes" are listed among Measles, Famines, Despots, and other "children of the four great bogies."[4]

- ^ Pater o'pee is an intricate solo dance involving stepping in and around sticks or staves laid crosswise on the ground.[5]

- ^ Ugly people are described as "like the poor Paddies who eat potatoes"; an extended passage discusses St. Brandan among the Irish who liked "to brew potheen, and dance the pater o'pee,[e] and knock each other over the head with shillelaghs, and shoot each other from behind turf-dykes, and steal each other's cattle, and burn each-other's homes". One character (Dennis) lies and says whatever he thinks others want to hear because "he is a poor Paddy, and knows no better". The statement that Irishmen always lie is used to explain why "poor ould Ireland does not prosper like England and Scotland".[4]

References

[edit]- ^ Hale, Piers J. (November 2013). "Monkeys into men and men into monkeys: Chance and contingency in the evolution of man, mind, and morals in Charles Kingsley's Water Babies". Journal of the History of Biology. 46 (4): 551–597. doi:10.1007/s10739-012-9345-5. PMID 23225100. S2CID 20627244.

- ^ Coles, Richard (11 July 2016). "Reverend Richard Coles on The Water Babies: how a vicar saved a chimney sweep". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Hoagwood, Terrence (Summer 1988). "Kingsley's young and old". Explicator. 46 (4): 18. doi:10.1080/00144940.1988.9933841.

- ^ a b c d e Sandner, David (2004). Fantastic Literature: A Critical Reader. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 328. ISBN 0-275-98053-7.

- ^ Wild Sports of the West. London, UK: W.H. Maxwell, E.P. 1850.

- ^ Holt, Jenny (September 2011). "'A Partisan Defence of Children'? Kingsley's The Water-Babies Re-Contextualized". Nineteenth-Century Contexts. 33 (4): 353–370. doi:10.1080/08905495.2011.598672. S2CID 192155414.

- ^ Milner, Richard (1990). The Encyclopedia of Evolution: Humanity's search for its origins. p. 458.

- ^ Darwin (1887), p. 287.

- ^ Kingsley, Charles (1863). The water-babies : a fairy tale for a land-baby. Fisher - University of Toronto. London ; Cambridge : Macmillan. p. 71.

- ^ Darwin (1860), p. 134

- ^ Kingsley, Charles. The Water-Babies. chapter VI, page 12. Retrieved 14 January 2013 – via Pagebypagebooks.com.

- ^ a b Huxley, Leonard (ed.). The Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley. Vol. 3. p. 256.

- ^ a b Wood, Naomi (1995). "A (Sea) Green Victorian: Charles Kingsley and The Water-Babies". The Lion and the Unicorn. 19 (2): 233–252. ISSN 1080-6563 – via Project Muse.

- ^ Judd, Catherine Nealy (March 2017). "Charles Kingsley's The Water Babies: Industrial England, The Irish Famine, and The American Civil War". Victorian Literature and Culture. 45 (1): 179–204. doi:10.1017/S1060150316000498. ISSN 1060-1503 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Garrick Theatre". The Times. London, UK. 19 December 1902. p. 4.

- ^ Kingsley, Charles (7 September 1998). The Water Babies (audio cassette). BBC Radio Collection. BBC Audiobooks. ISBN 978-0-563-55810-1.

A BBC Radio 4 full cast dramatisation.

- ^ Farley, P. (30 March 2013). Classic serial, The Water Babies: A modern fairy tale. Harding, Emma (director). BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ Ross, Fiona; Colverd, Fiona (2014). The Water Babies (musical). Last, David (music by).

- ^ "Stephanie Wickmere". mandy.com. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ "The Water Babies". cheltplayhouse.org.uk. What's On. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ The Water Babies (video) – via YouTube.

- ^ "The Water Babies : An opera in four acts with a prologue by Fred Hill". Australian Music Centre.

- Kingsley, Charles (1863). The Water-Babies. Oxford, UK & New York, NY: Oxford University Press (published 1995). ISBN 0-19-282238-1.

- Darwin, C. (1860). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (2nd ed.). London, UK: John Murray. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- Darwin, C. (1887). Darwin, F. (ed.). The life and letters of Charles Darwin, including an autobiographical chapter. London, UK: John Murray. Retrieved 20 July 2007. (contains The Autobiography of Charles Darwin)

External links

[edit]- Kingsley, C. (1915) [1863].

The full text of The Water-Babies, A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby at Wikisource. Robinson, W.H. (illustrator).

The full text of The Water-Babies, A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby at Wikisource. Robinson, W.H. (illustrator).  Media related to The Water Babies at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The Water Babies at Wikimedia Commons- The Water-Babies at Standard Ebooks

- The Water-Babies at Project Gutenberg

The Water-Babies public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Water-Babies public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Kingsley, C. (c. 1899) [1863]. "The Water-Babies" (full text & illustrations). Altemus, Henry (illustrator). Philadelphia, PA: H. Altemus – via Internet Archive (archive.org).

- 1863 British novels

- 1863 fantasy novels

- 1860s children's books

- Anti-Catholic publications

- British children's novels

- British fantasy novels

- British satirical novels

- Novels by Charles Kingsley

- British novels adapted into films

- Novels adapted into radio programs

- British novels adapted into plays

- Novels first published in serial form

- Works originally published in Macmillan's Magazine

- Charles Darwin

- Criticism of creationism

- Antisemitic novels

- Race-related controversies in literature

- Children's books set on islands