Groucho Marx

| Groucho Marx | |

|---|---|

Marx in Copacabana (1947) | |

| Birth name | Julius Henry Marx |

| Born | October 2, 1890 New York City, NY, U.S. |

| Died | August 19, 1977 (aged 86) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Eden Memorial Park Cemetery |

| Medium |

|

| Years active | 1905–1976 |

| Genres | |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | |

| Parent(s) | |

| Relative(s) |

|

Julius Henry "Groucho" Marx (/ˈɡraʊtʃoʊ/; October 2, 1890 – August 19, 1977) was an American comedian, actor, writer, and singer who performed in films and vaudeville on television, radio, and the stage.[1] He was a master of quick wit and is considered one of America's greatest comedians.[2]

Marx made 13 feature films as a team with his brothers, who performed under the name the Marx Brothers, of whom he was the third born. He also had a successful solo career, primarily on radio and television, most notably as the host of the game show You Bet Your Life.[1]

His distinctive appearance, carried over from his days in vaudeville, included quirks such as an exaggerated stooped posture, spectacles, cigar, and a thick greasepaint mustache (later a real mustache) and eyebrows. These exaggerated features resulted in the creation of one of the most recognizable and ubiquitous novelty disguises, known as Groucho glasses: a one-piece mask consisting of horn-rimmed glasses, a large plastic nose, bushy eyebrows and brush mustache.[3]

Early life

[edit]Julius Henry Marx was born on October 2, 1890, in Manhattan, New York City.[4] Marx stated that he was born in a room above a butcher's shop on East 78th Street, "Between Lexington and Third", as he told Dick Cavett in a 1969 television interview.[5] The Marx children grew up in a turn-of-the-century building at 179 East 93rd Street off Lexington Avenue in a neighborhood now known as Carnegie Hill on the Upper East Side of the borough of Manhattan. His older brother Harpo, in his memoir Harpo Speaks, called the building "the first real home I knew".[6] It was populated with European immigrants, mostly artisans. Just across the street were the oldest brownstones in the area, owned by people including the well-connected Loew Brothers and William Orth. The Marx family lived there "for about 14 years", Groucho also told Cavett.

Marx's family was Jewish.[7] His mother was Miene "Minnie" Schoenberg, whose family came from Dornum in northern Germany when she was 16 years old. His father was Simon "Sam" Marx, who changed his name from Marrix, and was called "Frenchie" by his sons throughout his life, because he and his family came from Alsace in France.[8] Minnie's brother was Al Schoenberg, who shortened his name to Al Shean when he went into show business as half of Gallagher and Shean, a noted vaudeville act of the early 20th century. According to Marx, when Shean visited, he would throw the local waifs a few coins so that when he knocked at the door he would be surrounded by adoring fans. Marx and his brothers respected his opinions and asked him on several occasions to write some material for them.[citation needed]

Minnie Marx did not have an entertainment industry career but had intense ambition for her sons to go on the stage like their uncle. While pushing her second son Leonard (Chico Marx) in piano lessons, she found that Julius had a pleasant soprano voice and the ability to remain on key. Julius's early career goal was to become a doctor, but the family's need for income forced him out of school at the age of twelve. By that time Julius had become a voracious reader, particularly fond of Horatio Alger. Marx continued to overcome his lack of formal education by becoming very well-read.[citation needed]

After a few stabs at entry-level office work and jobs suitable for adolescents, Marx took to the stage as a boy singer with the Gene Leroy Trio, debuting at the Ramona Theatre in Grand Rapids, Michigan, on July 16, 1905.[9] Marx reputedly claimed that he was "hopelessly average" as a vaudevillian, but this was typical Marx, wisecracking in his true form. By 1909, Minnie Marx had assembled her sons into an undistinguished vaudeville singing group billed as "The Four Nightingales". The brothers Julius, Milton (Gummo Marx) and Arthur (originally Adolph, but Harpo Marx from 1911) and another boy singer, Lou Levy, traveled the U.S. vaudeville circuits to little fanfare. After exhausting their prospects in the East, the family moved to La Grange, Illinois, to play the Midwest.[citation needed]

After a particularly dispiriting performance in Nacogdoches, Texas, Julius, Milton, and Arthur began cracking jokes onstage for their own amusement. Much to their surprise, the audience liked them better as comedians than as singers. They modified the then-popular Gus Edwards comedy skit "School Days" and renamed it "Fun In Hi Skule". The Marx Brothers performed variations on this routine for the next seven years.[citation needed]

For a time in Vaudeville, all the brothers performed using ethnic accents. Leonard, the oldest, developed the Italian accent he used as Chico Marx to convince some roving bullies that he was Italian, not Jewish. Arthur, the next oldest, donned a curly red wig and became "Patsy Brannigan", a stereotypical Irish character. His discomfort when speaking on stage led to his uncle Al Shean's suggestion that he stop speaking altogether and play the role in mime. Julius Marx's character from "Fun In Hi Skule" was an ethnic German, so Julius played him with a German accent. After the sinking of the RMS Lusitania in 1915, public anti-German sentiment was widespread, and Marx's German character was booed, so he dropped the accent and developed the fast-talking wise-guy character that became his trademark.[citation needed]

The Marx Brothers became the biggest comedic stars of the Palace Theatre in New York, which billed itself as the "Valhalla of Vaudeville". Brother Chico's deal-making skills resulted in three hit plays on Broadway. No other comedy routine had ever so infected the Broadway circuit. All of this stage work predated their Hollywood career. By the time the Marxes made their first movie, they were already major stars with sharply honed skills; and by the time Groucho was relaunched to stardom in television on You Bet Your Life, he had been performing successfully for half a century.[citation needed]

Career

[edit]Vaudeville

[edit]Marx started his career in vaudeville in 1905 when he joined up with an act called The Leroy Trio.[10] He answered a newspaper want ad by a man named Robin Leroy who was looking for a boy to join his group as a singer. Marx was hired along with fellow vaudeville actor Johnny Morris. Through this act, Marx got his first taste of life as a vaudeville performer. In 1909, Marx and his brothers had become a group act, at first called The Three Nightingales and later The Four Nightingales.[10] The brothers' mother, Minnie Marx, was the group's manager, putting them together and booking their shows. The group had a rocky start, performing in less than adequate venues and rarely, if ever, being paid for their performances.[10] Eventually brother Milton (Gummo) left the act to serve in World War I and was replaced by Herbert (Zeppo), and the group became known as the Marx Brothers.[10] Their first successful show was Fun In Hi Skule (1910).[10]

Motion Pictures

[edit]

Marx made 26 movies, including 13 with his brothers Chico and Harpo.[11] Marx developed a routine as a wisecracking hustler with a distinctive chicken-walking lope, an exaggerated greasepaint mustache and eyebrows and an ever-present cigar, improvising insults to stuffy dowagers (frequently played by Margaret Dumont) and anyone else who stood in his way. As the Marx Brothers, he and his brothers starred in a series of popular stage shows and movies.

Their first movie was a silent film made in 1921 that was only shown once in the Bronx,[11] and is believed to have been destroyed shortly afterward. A decade later, the team made their last two Broadway shows—The Cocoanuts and Animal Crackers[11]—into movies. Other successful films were Monkey Business, Horse Feathers, Duck Soup and A Night at the Opera.[11] One quip from Marx concerned his response to Sam Wood, the director of A Night at the Opera. Furious with the Marx Brothers' ad-libs and antics on the set, Wood yelled in disgust: "You can't make an actor out of clay." Marx responded, "Nor a director out of Wood."[12]

Marx also worked as a radio comedian and show host. One of his earliest stints was a short-lived series in 1932, Flywheel, Shyster and Flywheel, costarring Chico. Though most of the scripts and discs were thought to have been destroyed, all but one of the scripts were found in 1988 in the Library of Congress. In 1947, Marx was asked to host a radio quiz program You Bet Your Life. It was broadcast by ABC and then CBS before moving to NBC. It moved from radio to television on October 5, 1950, and ran for eleven years. It was largely sponsored by DeSoto automobiles and Marx sometimes appeared in the commercials. Filmed before an audience, the show consisted of Marx bantering with the contestants and ad-libbing jokes before briefly quizzing them. The announcer for the show was George Fenneman. The show was responsible for popularizing the phrases "Say the secret word and the duck will come down and give you fifty dollars," "Who's buried in Grant's Tomb?" and "What color is the White House?" (asked to reward a losing contestant a consolation prize).[13]

Throughout his career Marx introduced a number of memorable songs in films, including "Hooray for Captain Spaulding" and "Hello, I Must Be Going", in Animal Crackers, "Whatever It Is, I'm Against It", "Everyone Says I Love You" and "Lydia the Tattooed Lady". Frank Sinatra, who once quipped that the only thing he could do better than Marx was sing, made a film with Marx and Jane Russell in 1951 entitled Double Dynamite.

Mustache, eyebrows, and walk

[edit]In public and off-camera, Harpo and Chico were hard to recognize without their wigs and costumes, and it was almost impossible for fans to recognize Groucho without his trademark eyeglasses, fake eyebrows, and mustache.

The greasepaint mustache and eyebrows originated spontaneously prior to a vaudeville performance in the early 1920s when he did not have time to apply the pasted-on mustache he had been using (or, according to his autobiography, simply did not enjoy the removal of the mustache because of the effects of tearing an adhesive bandage off the same patch of skin every night). After applying the greasepaint mustache, a quick glance in the mirror revealed his natural hair eyebrows were too undertoned and did not match the rest of his face, so Marx added the greasepaint to his eyebrows and headed for the stage. The absurdity of the greasepaint was never discussed on-screen, but in a famous scene in Duck Soup, where both Chicolini (Chico) and Pinky (Harpo) disguise themselves as Groucho, they are briefly seen applying the greasepaint, implicitly answering any question a viewer might have had about where he got his mustache and eyebrows.

Marx was asked to apply the greasepaint mustache once more for You Bet Your Life when it came to television, but he refused, opting instead to grow a real one, which he wore for the rest of his life. By this time, his eyesight had weakened enough for him to actually need corrective lenses; before then, his eyeglasses had merely been a stage prop. He debuted this new, and now much-older, appearance in Love Happy, the Marx Brothers's last film as a comedy team.

Marx did paint the old character mustache over his real one on a few rare occasions, including a TV sketch with Jackie Gleason on the latter's variety show in the 1960s (in which they performed a variation on the song "Mister Gallagher and Mister Shean", co-written by Marx's uncle Al Shean) and the 1968 Otto Preminger film Skidoo. In his late 70s at the time, Marx remarked on his appearance: "I looked like I was embalmed." He played a mob boss called "God" and, according to Marx, "both my performance and the film were God-awful!"

The exaggerated walk, with one hand on the small of his back and his torso bent almost 90 degrees at the waist, was a parody of a fad from the 1880s and 1890s.[citation needed] Fashionable young men of the upper classes would affect a walk with their right hand held fast to the base of their spines, and with a slight lean forward at the waist and a very slight twist toward the right with the left shoulder, allowing the left hand to swing free with the gait. Edmund Morris, in his biography The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, describes a young Roosevelt, newly elected to the State Assembly, walking into the House Chamber for the first time in this trendy, affected gait, somewhat to the amusement of the older and more rural members.[14] Marx exaggerated this fad to a marked degree, and the comedic effect was enhanced by how out of date the fashion was by the 1940s and 1950s.

Personal life

[edit]

Marx's three marriages ended in divorce. His first wife was chorus girl Ruth Johnson (m. 1920–1942). He was 29 and she was 19 at the time of their wedding. The couple had two children, Arthur Marx and Miriam Marx. His second wife was Kay Marvis (m. 1945–1951), née Catherine Dittig,[15] former wife of Leo Gorcey. Marx was 54 and Kay was 21 at the time of their marriage. They had a daughter, Melinda Marx. His third wife was actress Eden Hartford (m. 1954–1969). He was 64 and she was 24 at the time of their wedding.

During the early 1950s, Marx described his perfect woman: "Someone who looks like Marilyn Monroe and talks like George S. Kaufman."[16]

Marx was denied membership in an informal symphonietta of friends (including Harpo) organized by Ben Hecht, because he could play only the mandolin. When the group began its first rehearsal at Hecht's home, Marx rushed in and demanded silence from the "lousy amateurs". The musicians discovered him conducting the Los Angeles Symphony Orchestra in a performance of the overture to Tannhäuser in Hecht's living room. Marx was allowed to join the symphonietta.[17]

Later in life, Marx would sometimes note to talk show hosts, not entirely jokingly, that he was unable to actually insult anyone, because the target of his comment would assume that it was a Groucho-esque joke, and would laugh.[citation needed]

Despite his lack of formal education, he wrote many books, including his autobiography, Groucho and Me, (1959) and Memoirs of a Mangy Lover (1963). He was a friend of such literary figures as Booth Tarkington, T. S. Eliot, and Carl Sandburg. Much of his personal correspondence with those and other figures is featured in the book The Groucho Letters (1967) with an introduction and commentary on the letters written by Marx, who donated his letters to the Library of Congress.[18] His daughter Miriam published a collection of his letters to her in 1992 titled Love, Groucho.

In Life with Groucho: A Son's Eye View, Arthur Marx relates that in his latter years, Groucho increasingly referred to himself by the name Hackenbush, referring to the character of that name he played in A Day at the Races.[19]

Marx made serious efforts to learn to play the guitar. In the 1932 film Horse Feathers, he performs the film's love theme "Everyone Says I Love You" for costar Thelma Todd on a Gibson L-5.[20]

In July 1937, an America-vs.-England pro-celebrity tennis doubles match was organized, featuring Marx and Ellsworth Vines playing against Charlie Chaplin and Fred Perry, to open the new clubhouse at the Beverly Hills Tennis Club. Marx appeared on court with twelve rackets and a suitcase, leaving Chaplin—who took tennis seriously—bemused, before he asked what was in it. Marx asked Chaplin what was in his, with Chaplin responding he didn't have one. Marx replied, "What kind of tennis player are you?" After playing only a few games, Marx sat on the court and unpacked an elaborate picnic lunch from his suitcase.[21]

Irving Berlin quipped: "The world would not be in such a snarl, had Marx been Groucho instead of Karl."[22] In his book The Groucho Phile, Marx says "I've been a liberal Democrat all my life", and "I frankly find Democrats a better, more sympathetic crowd.... I'll continue to believe that Democrats have a greater regard for the common man than Republicans do".[23] However, during an episode of Firing Line on July 7, 1967, Marx admitted to voting for Wendell Willkie, the Republican candidate for president in 1940, over Franklin D. Roosevelt, stating that he did not believe that any man should run for more than two terms.[24] Marx mentioned in a television interview that he disliked the women's liberation movement.[citation needed]

Later years

[edit]You Bet Your Life

[edit]Marx's radio career was not as successful as his work on stage and in film, though historians such as Gerald Nachman and Michael Barson suggest that, in the case of the single-season Flywheel, Shyster, and Flywheel (1932), the failure may have been a combination of a poor time slot and the Marx Brothers' returning to Hollywood to make another film.

In the mid-1940s, he weathered a depressing lull in his career. His radio show Blue Ribbon Town had failed, and he was unable to sell his proposed sitcom The Flotsam Family only to see it become a huge hit as The Life of Riley with William Bendix in the title role. By that time, the Marx Brothers as film performers had officially retired.

Marx was scheduled to appear on a radio show with Bob Hope. Annoyed that he was made to wait in the green room for 40 minutes, he went on the air in a foul mood. Hope started by saying "Why, Groucho Marx! Groucho, what are you doing out here in the desert?" Marx retorted, "Huh, desert, I've been sitting in the dressing room for forty minutes! Some desert alright ...". Marx continued to ignore the script, ad-libbing at length, and took it well beyond its allotted time slot.

Listening in on the show was producer John Guedel, who had a brainstorm. He approached Marx about doing a quiz show, to which Marx derisively retorted, "A quiz show? Only actors who are completely washed up resort to a quiz show!" Undeterred, Guedel proposed that the quiz would be only a backdrop for Marx's interviews of people, and the storm of ad-libbing that they would elicit. Marx replied, "Well, I've had no success in radio, and I can't hold on to a sponsor. At this point, I'll try anything!"[citation needed]

You Bet Your Life debuted in October 1947 on ABC radio (which aired it from 1947 to 1949), sponsored by costume jewelry manufacturer Allen Gellman;[25] and then on CBS (1949–50), and finally NBC. The show was on radio only from 1947 to 1950; on both radio and television from 1950 to 1960; and on television only, from 1960 to 1961. The show proved a huge hit, being one of the most popular on television by the mid-1950s, garnering a number one rating in 1953. With George Fenneman as his announcer and straight man, Marx entertained his audiences with rapier wit and improvised conversation with his guests. Since You Bet Your Life was mostly ad-libbed and unscripted — although writers did pre-interview the guests and feed Marx ready-made lines in advance — the producers insisted that the network prerecord it instead of it being broadcast live. There were three reasons for this: prerecording provided Marx with time to fish around for funny exchanges, any intervening dead spots could be edited out; and most importantly to protect the network from what was considered risqué, since Marx was a notorious loose cannon and known to say almost anything. The television show ran for 11 seasons until it was canceled in 1961. Ironically longtime major sponsor, automobile marque DeSoto went out of business for declining sales that same year. For the DeSoto ads, Marx would sometimes say: "Tell 'em Groucho sent you", or "Try a DeSoto before you decide." In the mid-1970s, episodes of the show were syndicated and rebroadcast as The Best of Groucho.[26]

The program's theme music was an instrumental version of "Hooray for Captain Spaulding," which became increasingly identified as Marx's personal theme song. A recording of the song with Marx and the Ken Lane singers with an orchestra directed by Victor Young was released in 1952. Another recording made by Marx during this period was "The Funniest Song in the World," released on the Young People's Records label in 1949. It was a series of five original children's songs with a connecting narrative about a monkey and his fellow zoo creatures.

One of Marx's most oft-quoted remarks may have occurred during a 1947 radio episode. Marx was interviewing Charlotte Story, who had borne 20 children. When Marx asked why she had chosen to raise such a large family, Mrs. Story is said to have replied, "I love my husband," to which Marx responded, "I love my cigar, but I take it out of my mouth once in a while." The remark was judged too risqué to be aired, according to the anecdote, and was edited out before broadcast.[27] Charlotte Story and her husband Marion, indeed parents of 20 children, were real people who appeared on the program.[28] Audio recordings of the interview exist,[29] and a reference to cigars is made ("With each new kid, do you go around passing out cigars?"), but there is no evidence of the claimed remark. "I get credit all the time for things I never said," Marx told Roger Ebert in 1972. "You know that line in You Bet Your Life? The guy says he has seventeen kids and I say, 'I smoke a cigar, but I take it out of my mouth occasionally'? I never said that."[30] Marx's 1976 memoir recounts the episode as fact,[31] but co-writer Hector Arce relied mostly on sources other than Marx himself—who was by then in his mid eighties, in ill health and mentally compromised—and was probably unaware that Marx had specifically denied making the observation.[32] Head writer Bernie Smith recalled in a 1996 interview that the remark was indeed made—but again, well after the fact.[33]

In 1946, as part of the marketing campaign for the Marx Brothers film A Night in Casablanca, Marx created a storyline that Warner Bros. Pictures threatened to sue him, contending that that title was too similar to their 1942 film Casablanca.[34] Groucho wrote open letters "responding" to the four Warner brothers, including one in which he questions their own use of various words, such as: wondering if "in 1471, Ferdinand Balboa Warner, your great-great-grandfather,... stumbled on the shores of Africa and... named it Casablanca"; suggesting that "[David] Burbank's survivors aren't too happy with the fact that" Warner Bros. Burbank, California studios are called their "Burbank studios"; and even suggesting a Marx Brothers legal action addressing "What about 'Warner Brothers'? ... Professionally, we were brothers long before you were."[35][36]

Other work

[edit]On August 5, 1948, Marx's comedy play April Fool premiered at the Lobero Theatre in Santa Barbara, California, to mediocre reviews.[37] Penned by Groucho Marx and Norman Krasna, the play was rewritten and retitled Time for Elizabeth, and opened at the Fulton Theatre in New York City on September 27, 1948,[38] where it closed after only eight performances.[39] [40]

By the time You Bet Your Life debuted on TV on October 5, 1950, Marx had grown a real mustache (which he had already sported earlier in the films Copacabana and Love Happy).

During a tour of Germany in 1958, accompanied by then-wife Eden, daughter Melinda, Robert Dwan and Dwan's daughter Judith, he climbed a pile of rubble that marked the site of Adolf Hitler's bunker, the site of Hitler's death, and performed a two-minute Charleston.[41] He later remarked to Richard J. Anobile in The Marx Brothers Scrapbook, "Not much satisfaction after he killed six million Jews!"

In 1960, Marx, a lifelong devotee of the comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan, appeared as Ko-Ko, the Lord High Executioner, in a televised production of The Mikado on NBC's The Bell Telephone Hour. A clip of this is in rotation on Classic Arts Showcase.

Another TV show, Tell It to Groucho, premiered January 11, 1962, on CBS, but only lasted five months. On October 1, 1962, Marx, after acting as occasional guest host of The Tonight Show during the six-month interval between Jack Paar and Johnny Carson, introduced Carson as the new host.

In 1964, Marx starred in the "Time for Elizabeth" episode of Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre, a truncated version of a play that he and Norman Krasna wrote in 1948.

In 1965, Marx starred in a weekly show for British TV titled Groucho, broadcast on ITV. The program was along similar lines to You Bet Your Life, with Keith Fordyce taking on the Fenneman role. However, it was poorly received and lasted only 11 weeks.

Marx appeared as a gangster named God in the comedy movie Skidoo (1968), directed by Otto Preminger, and starring Jackie Gleason and Carol Channing. It was released by the studio where the Marx Brothers began their film career, Paramount Pictures. The film received almost universally negative reviews. Writer Paul Krassner published a story in the February 1981 issue of High Times, relating how Marx prepared for the LSD-themed movie by taking a dose of the drug in Krassner's company, and had a moving, largely pleasant experience.[42]

Marx developed friendships with rock star Alice Cooper—the two were photographed together for Rolling Stone magazine—and television host Dick Cavett, becoming a frequent guest on Cavett's late-night talk show, even appearing in a one-man, 90-minute interview.[5] When Elton John was visiting California in 1972, he and Marx became friendly. Marx insisted on calling him "John Elton". According to writer Philip Norman, when Elton John was playing the piano at Marx's home, Marx jokingly pointed his index fingers as if holding a pair of six-shooters; John put up his hands and said, "Don't shoot me, I'm only the piano player," thereby giving him the title of the album he had just completed. A film poster for the Marx Bros. film Go West is visible on the album cover photograph as an homage to Marx. Elton John accompanied Marx to a performance of Jesus Christ Superstar. As the lights went down, Marx called out, "Does it have a happy ending?" And during the Crucifixion scene, he declared, "This is sure to offend the Jews."[citation needed]

Marx's previous work regained popularity; new books of transcribed conversations were published by Richard J. Anobile and Charlotte Chandler. In a BBC interview in 1975, Marx called his greatest achievement having a book selected for cultural preservation in the Library of Congress. In a Cavett interview in 1971,[43] Marx said being published in The New Yorker under his own name,[44] Julius Henry Marx, meant more than all the plays he appeared in.[5] As a man who never had formal schooling, to have his writings declared culturally important was a point of great satisfaction.

As he passed his 81st birthday in 1971, Marx became increasingly frail, physically and mentally, as a result of a succession of minor strokes and other health issues.[45][46] In 1972, largely at the behest of his companion Erin Fleming, Marx staged a live one-man show at Carnegie Hall that was later released as a double album, An Evening with Groucho, on A&M Records. He also made an appearance in 1973 on a short-lived variety show hosted by Bill Cosby. Fleming's influence on Marx was controversial. Some close to Marx believed that she did much to revive his popularity, and the relationship with a younger woman boosted his ego and vitality.[47] Others described her as a Svengali, exploiting an increasingly senile Marx in pursuit of her own stardom. Marx's children, particularly Arthur, felt strongly that Fleming was pushing their weak father beyond his physical and mental limits.[46] Writer Mark Evanier concurred.[48]

On the 1974 Academy Awards telecast (which was Groucho Marx's final major public appearance), Jack Lemmon presented him with an honorary Academy Award to a standing ovation. The award honored Harpo, Chico, and Zeppo as well: "in recognition of his brilliant creativity and for the unequalled achievements of the Marx Brothers in the art of motion picture comedy". Noticeably frail, Marx took a bow for his deceased brothers, saying that "I wish that Harpo and Chico could be here to share with me this great honor." (Zeppo, still alive, was in the audience). He also praised the late Margaret Dumont as a great straight woman who never understood any of his jokes.[5][49] Marx's final appearance was a brief sketch with George Burns in the Bob Hope television special Joys (a parody of the 1975 movie Jaws) in March 1976.[50] His health continued to decline the following year; when his younger brother Gummo died at age 83 on April 21, 1977, Marx was never told for fear of eliciting still further deterioration of his health.[51]

Marx maintained his irrepressible sense of humor to the very end, however. George Fenneman, his radio and TV announcer, good-natured foil, and lifelong friend, often related a story of one of his final visits to Marx's home: When the time came to end the visit, Fenneman lifted Marx from his wheelchair, put his arms around his torso, and began to "walk" the frail comedian backwards across the room towards his bed. As he did, he heard a weak voice in his ear: "Fenneman," whispered Marx, "you always were a lousy dancer."[52] When a nurse approached him with a thermometer during his final hospitalization, explaining that she wanted to see if he had a temperature, he responded, "Don't be silly—everybody has a temperature."[47] Actor Elliott Gould recalled a similar incident: "I recall the last time I saw Groucho, he was in the hospital, and he had tubes in his nose and what have you," he said. "And when he saw me, he was weak, but he was there; and he put his fingers on the tubes and played them like it was a clarinet. Groucho played the tubes for me, which brings me to tears."[53]

Death

[edit]

Marx was hospitalized at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center with pneumonia on June 22, 1977, and died there nearly two months later at the age of 86[54] on August 19, four months after Gummo's death.[1] Media coverage of Groucho's death and legacy was overshadowed by the sudden death of Elvis Presley three days earlier.

Marx's body was cremated and the ashes are interred in the Eden Memorial Park Cemetery in Los Angeles. He was survived by his three children and younger brother Zeppo, who outlived him by two years. His gravestone bears no epitaph but in one of his last interviews he suggested one: "Excuse me, I can't stand up."[55]

Litigation over his estate lasted into the 1980s. Eventually, his three children were awarded the bulk of the estate, while Erin Fleming, his companion during his final years, was ordered to repay $472,000.[56]

Legacy

[edit]

Groucho Marx was considered the most recognizable of the Marx Brothers. Groucho-like characters and references have appeared in popular culture both during and after his life, some aimed at audiences who may never have seen a Marx Brothers movie. Marx's trademark eyeglasses, nose, mustache, and cigar have become icons of comedy—glasses with fake noses and mustaches (referred to as "Groucho glasses", "nose-glasses," and other names) are sold by novelty and costume shops around the world.

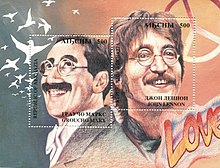

The cover of The Firesign Theatre's 1969 album, How Can You Be in Two Places at Once When You're Not Anywhere at All, subtitled All Hail Marx and Lennon, features images of Groucho Marx and John Lennon.

Nat Perrin, close friend of Groucho Marx and writer of several Marx Brothers films, inspired John Astin's portrayal of Gomez Addams on the 1960s TV series The Addams Family with similarly thick mustache, eyebrows, sardonic remarks, backward logic, and ever-present cigar (pulled from his breast pocket already lit).[58]

Minnie's Boys, a 1970 Broadway musical, focused on the younger years of Marx (played by Lewis J. Stadlen), his brothers, and his mother (played by Shelley Winters). Marx received credit as the show's advisor and appeared on The Dick Cavett Show to promote the production.[59][60]

As Groucho Marx once said, 'Anyone can get old—all you have to do is to live long enough'.

—Queen Elizabeth II speaking at her 80th birthday celebration in 2006.[61]

In 1972, at Cannes, Marx was made a Commander in the French Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, an honor he was very proud of.[62]

A meeting with Elton John led to a press photo of Marx pointing both of his index fingers and thumbs at Elton like revolvers. John's spontaneous response of holding up his hands and replying, "Don't shoot me! I'm only the piano player!" was so amusing that Elton John reused it as the title of a 1973 album. An added Marx homage was that a poster for the Marx Brothers' movie Go West was included on the cover art.[63]

Marx was also known to influence the Warner Bros. cartoon character Bugs Bunny, who recited his famous line "Of course you realize this means war!" in two of his cartoons in the Looney Tunes series, Long-Haired Hare and Bully for Bugs, when his antagonist has offended him.

Two albums by British rock band Queen, A Night at the Opera (1975) and A Day at the Races (1976), are named after Marx Brothers films. In March 1977, Marx invited Queen to visit him in his Los Angeles home; there they performed "'39" a cappella.[64]

A long-running ad campaign for Vlasic Pickles features an animated stork that imitates Marx's mannerisms and voice.[65] On the famous Hollywood Sign in California, one of the "O"s is dedicated to Marx. Alice Cooper contributed over $27,000 to remodel the sign, in memory of his friend.[66]

Actor Frank Ferrante has performed as Groucho Marx on stage since 1986. He continues to tour under rights granted by the Marx family in a show entitled An Evening with Groucho in theaters throughout the United States and Canada with supporting actors and piano accompanist Jim Furmston. In the late 1980s, Ferrante starred as Marx in the off-Broadway and London show Groucho: A Life in Revue, penned by Marx's son Arthur. Ferrante portrayed the comedian from age 15 to 85. The show was later filmed for PBS in 2001. In 1982, Gabe Kaplan filmed a version of the same show, entitled Groucho.[67]

In the Hungarian dubbed version of Woody Allen's film Annie Hall, a famous quotation told by Alvy Singer (Allen) at the beginning of the film is not attributed to Groucho Marx as in the original, but to Buster Keaton. The reason was that in communist Hungary, the name 'Marx' was associated with Karl Marx, and the name was not allowed to be used in such a light, humorous context.[68]

Woody Allen's 1996 musical Everyone Says I Love You, in addition to being named for one of Marx's signature songs, ends with a Groucho-themed New Year's Eve party in Paris, which some of the stars, including Allen and Goldie Hawn, attend in full Groucho costume. The highlight of the scene is an ensemble song-and-dance performance of "Hooray for Captain Spaulding"—done entirely in French.

In 2008, Minnie's Boys was remounted Off-Broadway with Erik Liberman as Groucho and Pamela Myers as Minnie Marx.[69] Liberman later played Marx in a musical based on Flywheel, Shyster, and Flywheel called The Most Ridiculous Thing You Ever Hoid (2010) and at the Obama White House.[70][71]

Groucho, a supporting character in the Italian horror comics series Dylan Dog, is a Groucho Marx impersonator whose character became his permanent personality, and he works with Dylan Dog as his professional sidekick. In the English-language version by Dark Horse Comics, to avoid legal complications regarding Groucho Marx's estate, the art was altered so that Groucho no longer sports the Marx brother's signature moustache, and was renamed Felix.[72]

Throughout the M*A*S*H television series, several Groucho homage traits are mirrored in Alan Alda's portrayal of Hawkeye, including the 1972 season one episode "Yankee Doodle Doctor" that had a full Groucho impression complete with nose, moustache and glasses.[73]

In 2023, notable artist William Kentridge included a drawing of Marx in his solo museum exhibition at The Broad in Los Angeles.[74]

Filmography

[edit]Features

[edit]| Title | Year | Role | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humor Risk | 1921 | Villain | Previewed once and never released; thought to be lost | |

| The Cocoanuts | 1929 | Hammer | Released by Paramount Pictures; based on a 1925 Marx Brothers Broadway musical | |

| Animal Crackers | 1930 | Captain Jeffrey Spaulding | Released by Paramount; based on a 1928 Marx Brothers Broadway musical | |

| The House That Shadows Built | 1931 | Caesar's Ghost | Short subject; non-theatrical promotional release by Paramount | |

| Monkey Business | 1931 | Groucho | Released by Paramount | |

| Horse Feathers | 1932 | Professor Quincy Adams Wagstaff | Released by Paramount | |

| Duck Soup | 1933 | Rufus T. Firefly | Released by Paramount | |

| Post-Zeppo | ||||

| A Night at the Opera | 1935 | Otis B. Driftwood | Released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer | |

| A Day at the Races | 1937 | Dr. Hugo Z. Hackenbush | Released by MGM | |

| Room Service | 1938 | Gordon Miller | Released by RKO Radio Pictures; based on a 1937 Broadway play | |

| At the Circus | 1939 | J. Cheever Loophole | Released by MGM | |

| Go West | 1940 | S. Quentin Quale | Released by MGM | |

| The Big Store | 1941 | Wolf J. Flywheel | Released by MGM (intended to be their last film) | |

| A Night in Casablanca | 1946 | Ronald Kornblow | Released by United Artists | |

| Love Happy | 1949 | Detective Sam Grunion | Released by United Artists | |

| Showdown at Ulcer Gulch | 1957 | Stage Conductor (voice) | Cameo | |

| The Story of Mankind | 1957 | Peter Minuit | Cameo | |

| General Electric Theater | 1959 | Suspect in a Police Lineup | Episode: "The Incredible Jewel Robbery" | |

| Title | Year | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yours for the Asking | 1936 | Sunbather | Uncredited cameo |

| The King and the Chorus Girl | 1937 | — | Co-writer with Norman Krasna |

| Instatanes | 1943 | Unknown | |

| Copacabana | 1947 | Lionel Q. Deveraux | Released by United Artist |

| Mr. Music | 1950 | Himself | Released by Paramount Pictures |

| You Bet Your Life | 1950–61 | Himself (host) | Quiz show |

| Double Dynamite | 1951 | Emile J. Keck | Released by RKO |

| A Girl in Every Port | 1952 | Benjamin Linn | Released by RKO |

| Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? | 1957 | George Schmidlap | Uncredited; released by 20th Century Fox |

| The Bell Telephone Hour | 1960 | Ko-Ko | Episode: "The Mikado" (aired April 29, 1960) |

| General Electric Theater | 1962 | John Graham | Episode: "The Hold-Out" |

| Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre | 1964 | Ed Davis | Episode: "Time For Elizabeth" |

| I Dream of Jeannie | 1967 | Himself | Episode: "The Greatest Invention in the World"[75] |

| Skidoo | 1968 | God | Released by Paramount |

| Julia | 1968 | Mr. Flywheel | Episode: "Farewell, My Friends, Hello" |

Short subjects

[edit]- Hollywood on Parade No. 11 (1933)

- Screen Snapshots Series 16, No. 3 (1936)

- Sunday Night at the Trocadero (1937)

- Screen Snapshots: The Great Al Jolson (1955)

- Showdown at Ulcer Gulch (1956) (voice)

- Screen Snapshots: Playtime in Hollywood (1956)

Bibliography

[edit]Books by Groucho Marx

[edit]- Beds (Farrar & Rinehart, 1930)

- Beds: revised & updated edition (Bobbs-Merrill, 1976 ISBN 0-672-52224-1)

- Many Happy Returns: An Unofficial Guide to Your Income-Tax Problems Illustrated by Otto Soglow (Simon & Schuster, 1942)

- Groucho and Me (B. Geis Associates, 1959)

- Memoirs of a Mangy Lover (B. Geis Associates, 1963)

- The Groucho Letters: Letters From and To Groucho Marx (Simon & Schuster, 1967, ISBN 0-306-80607-X)

- The Marx Bros, Scrapbook with Richard Anobile (Darien House/W W Norton, 1973, ISBN 0-393-08371-3)

- The Secret Word Is Groucho with Hector Arce (Putnam, 1976)

- The Groucho Phile: An Illustrated Life by Groucho Marx with Hector Arce (Galahad, 1976, ISBN 0-88365-433-4)

Essays and reporting

[edit]- Marx, Julius H. (April 4, 1925). "Boston again". New York, Etc. The New Yorker. Vol. 1, no. 7. p. 25.

- — (April 11, 1925). "Vaudeville talk". New York, Etc. The New Yorker. Vol. 1, no. 8. p. 25.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Groucho Marx, Comedian, Dead. Movie Star and TV Host Was 86. Master of the Insult. Groucho Marx, Film Comedian and Host of 'You Bet Your Life,' Dies". The New York Times. August 20, 2007. p. 1.

- ^ Billboard Magazine May 4, 1974, pg 35: "Groucho Marx was the best comedian this country ever produced – Woody Allen"

- ^ Giddins, Gary (2001). The New York Times Book Reviews 2000, volume 1. Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. ISBN 1-57958-058-0. "The most enduring masks of the 20th century—likely to take their place alongside Comedy and Tragedy or Pulcinella and Pierrot"

- ^ The WWI draft registration of 1917 as Julius Henry Marx in Chicago, Illinois uses October 2, 1890. The 1900 census has him born in October 1890.

- ^ a b c d "The Dick Cavett Show - 6/13/1969". Dickcavettshow.com. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ Marx, Harpo; Rowland, Barber (with) (1961). Harpo Speaks (1985 with new Afterwords ed.). New York: Limelight Editions. p. 19. ISBN 0-87910-036-2. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ^ Gary Baum (June 23, 2011). "L.A.'s Power Golf Clubs: Where the Hollywood Elite Play". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Bland, Frank. "The Marx Brothers Family". Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ Bader, Robert S. (2016). Four of the Three Musketeers: The Marx Brothers on Stage. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. p. 31. ISBN 9780810134164.

- ^ a b c d e DesRochers, Rick (2014). The New Humor in the Progressive Era. New York, New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 83, 84, 85. ISBN 978-1-137-35742-7.

- ^ a b c d "Groucho Marx Biography". Groucho-marx.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

- ^ Boller, Paul F.; Davis, Ronald L. (1988). Hollywood Anecdotes (reprint ed.). Ballantine Books. p. 220. ISBN 0-345-35654-3.

- ^ Kanfer, Stefan (2000). The Essential Groucho: Writings by, for and about Groucho Marx. New York: Random House. p. 209. ISBN 037570213X.

- ^ Morris, Edmund (2001). The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt (Modern Library Paperback ed.). New York: Modern Library. pp. 143–144. ISBN 0-375-75678-7. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

- ^ Boxoffice, 3 June 1939, p. 89[permanent dead link].

- ^ Marx, Arthur (1954). Life With Groucho. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 294. LCCN 54-9802 – via Internet Archive text collection.

- ^ Friedrich, Otto (1997). "Ingatherings (1940)". City of Nets: A Portrait of Hollywood in the 1940s (reprint ed.). Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 43. ISBN 0520209494.

- ^ "Groucho Marx papers, 1930-1967". Library of Congress Online Catalog. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- ^ Marx, Arthur (1954). Life With Groucho. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 200. LCCN 54-9802 – via Internet Archive text collection.

- ^ Jerry McCulley, The Surprisingly Serious Tale of Comedian Groucho Marx and His Lifelong Quest to Master Guitar. Archived May 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Leigh, Danny (January 2, 2015). "The Marx brothers on film: souped-up comedy". Financial Times. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ Irving Berlin, Robert Kimball, Linda Emmet. The Complete Lyrics of Irving Berlin, p. 489. Hal Leonard Corporation, 2005. ISBN 1-55783-681-7

- ^ Marx, Groucho. The Groucho Phile, p. 238. Wallaby, 1977.

- ^ "Firing Line with William F. Buckley Jr.: Is the World Funny?". YouTube. January 25, 2017.

- ^ Charlotte Chandler. Hello, I must be going: Groucho and his friends. Doubleday, 1978, p 190

- ^ Kleiner, Dick (August 23, 1975). "Groucho's straight man back". The Anniston Star. Anniston, Alabama. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Dwan, R. As Long As They're Laughing : Groucho Marx and You Bet Your Life. Baltimore, Midnight Marquee, 2000, p. 129. ISBN 188766436X

- ^ Kanfer, S. Groucho: The Life and Times of Julius Henry Marx. New York, Vintage, May 2001, p. 136. ISBN 0375702075

- ^ "The Secret Words". Snopes.com. February 15, 2001. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ Ebert, R. A Living Legend, Rated R. Esquire, July 1972, p. 143. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ^ Marx, G. and Arce, H. The Secret Word is Groucho. New York, G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1976, pp. 33–4. ISBN 0399116907.

- ^ Kaltenbach, C. Also 20 Years Dead: Groucho. Baltimore Sun, August 19, 1997, p. E-1.

- ^ Stoliar, S. Raised Eyebrows: My Years Inside Groucho's House. New York, BearManor Media, October 2011, pp. 124–5. ISBN 1593936524

- ^ Clifton Fadiman (ed), Little Brown Book of Anecdotes, Boston 1985, p. 387

- ^ "Groucho Marx letter to Warner Brothers". Retrieved February 5, 2007 – via Internet Archive text collection.

- ^ David Mikkelson (September 10, 2000), A Night in Casablancaː Did Warner Bros. threaten to sue the Marx Brothers over their 1946 film titled 'A Night in Casablanca'?, Wikidata Q123469979

- ^ "The Los Angeles Times 07 Aug 1948, page 8". Newspapers.com. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ "Daily News 28 Sep 1948, page 280". Newspapers.com. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ "Groucho Marx "APRIL FOOL" Otto Kruger / Norman Krasna 1948 FLOP Tryout Playbill | #1860471580". Worthpoint. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ "Daily News 01 Oct 1948, page 1013". Newspapers.com. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ Hallett, Judith Dwan. "What's So Funny & Why?". Sarah Lawrence College. Archived from the original on December 16, 2007. Retrieved July 29, 2007.

- ^ Krassner, Paul (October 2, 2019). "High Times Greats: My Acid Trip With Groucho". High Times. Archived from the original on July 2, 2022. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

- ^ "The Dick Cavett Show - 5/25/1971". Dickcavettshow.com. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ "Groucho Marx - Contributors". newyorker.com. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- ^ Point of View Archived October 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, Mark Evanier, 1999-06-04, retrieved, August 9, 2007.

- ^ a b Point of View Archived July 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Mark Evanier, 1999-06-11, retrieved, August 9, 2007.

- ^ a b "They Dressed like Groucho" NY Times Opinionator (April 20, 20120 Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ Erin Fleming, R.I.P., Mark Evanier, March 7, 2004

- ^ "Groucho Marx receiving an Honorary Oscar®". Oscars.org. November 24, 2009. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2013.

- ^ "Bob Hope Special: Bob Hope in Joys". Hope Enterprises. March 5, 1976. Archived from the original on February 10, 2017. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ^ "Gummo Marx, Managed Comedians". The New York Times.

Palm Springs, California, April 21, 2007 (Reuters) Gummo Marks, an original member of the Marx brothers' comedy team, died here today. He was 84 years old.

- ^ "George Fenneman, Sidekick To Groucho Marx, Dies at 77". The New York Times. Associated Press. June 5, 1997. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ Famed Actor Elliott Gould Recalls Groucho Marx's Final Days (July 10, 2013). Compassion & Choices Magazine archive Archived January 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ^ "Groucho Marx Dies at 86 After Two-Month Illness". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. August 20, 1977.

Officials at Cedar-Sinai Medical Center, where Marx had been hospitalized for the past two months with a respiratory ailment, said he died at 7:25 p.m. PDT of pneumonia

- ^ Groucho the Great. legacy.com. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ Los Angeles Times, April 15, 2011, Obituary of Arthur Marx, "In his father's declining years, Marx became a central figure behind a successful legal battle to wrest back control of Groucho's affairs from his late-in-life companion, Erin Fleming."

- ^ Philatelists Just Wanna Have Fun, The New York Times, April 28, 1995.

- ^ "The return of Gomez Addams". Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "Minnie's Boys". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ Jones, J. R. (September 22, 2014). "The Marx Brothers TV Collection follows the legendary comedy team into the 1950s, '60s, and '70s". Chicago Reader. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ "Groucho marks Queen's 80th" Archived August 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. SBS. Retrieved June 27, 2017

- ^ "Attempted Bloggery: Groucho's French Order of Arts and Letters". Attemptedbloggery.blogspot.com. March 11, 2014. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ Buckley, David (2007). Elton The Biography. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1556527135.

- ^ Queen: The Ultimate Illustrated History of the Crown Kings of Rock. p.96. Voyageur Press, 2009

- ^ Stuart Elliott, Pink or Blue? These Bundles of Joy Are Always Green, The New York Times, May 30, 2007.

- ^ "A Sign is Reborn: 1978". The Hollywood Sign. June 29, 2017. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ Erickson, Hal (2013). "Gabe Kaplan As Groucho". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 21, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ "Már 40 éve nem szeretnénk olyan klubhoz tartozni, amelyik elfogadna tagnak". hvg.hu. April 20, 2017. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- ^ Gans, Andrew (May 16, 2008). "Liberman Will Join Myers in Mufti Minnie's Boys". Playbill. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ "Erik Liberman To Star As Groucho In IN MOST RIDICULOUS THING YOU EVER HOID 9/31". Broadway World. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ Markowitz, Joel (April 2, 2012). "Erik Liberman on Playing The Baker in Centerstage's 'Into the Woods' by Joel Markowitz". DC Metro Theater Arts. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ "Groucho (character)". Comic Vine. July 20, 2020. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ RJ (October 6, 2014). "Episode Spotlight: Yankee Doodle Doctor". mash4077tv.com. Archived from the original on December 10, 2022. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ^ Amadour (December 7, 2022). "15 Minutes With Visionary Artist William Kentridge". LAmag - Culture, Food, Fashion, News & Los Angeles. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ "Groucho Marx on Television Part Two - The Sixties and Seventies". TVparty.com. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Miriam Marx Allen, Love, Groucho: Letters From Groucho Marx to His Daughter Miriam (1992, ISBN 0-571-12915-3)

- Charlotte Chandler, Hello, I Must Be Going! (1979, ISBN 0-14-005222-4)

- Robert Dwan, As Long as They're Laughing: Groucho Marx and You Bet Your Life (2000, ISBN 1-887664-36-X)

- Stefan Kanfer, Groucho: The Life and Times of Julius Henry Marx (2000, ISBN 0-375-70207-5)

- Simon Louvish, Monkey Business: The Lives and Legends of the Marx Brothers (2001, ISBN 0-312-25292-7)

- Arthur Marx, Son of Groucho (1972, ISBN 0-679-50355-2)

- Glenn Mitchell, The Marx Brothers Encyclopedia (1996, ISBN 0-7134-7838-1)

- Steve Stoliar, Raised Eyebrows: My Years Inside Groucho's House (1996, ISBN 1-881649-73-3)

- Julius H. (Groucho) Marx v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 29 T.C. 88 (1957)

External links

[edit]- "Groucho Marx - Contributors". newyorker.com.

- Groucho Marx at IMDb

- Groucho Marx at the TCM Movie Database

- Groucho Marx at the Internet Broadway Database

- Works by or about Groucho Marx at the Internet Archive

- Groucho Marx Interview – Press Conference London June 1965 (audio file)

- FBI Records: The Vault - Groucho Marx at vault.fbi.gov

- The Marx Brothers Museum

- 1890 births

- 1977 deaths

- 20th-century American comedians

- 20th-century American Jews

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American male singers

- 20th-century American singers

- Academy Honorary Award recipients

- American game show hosts

- American male comedians

- American male film actors

- American male musical theatre actors

- American male stage actors

- American male television actors

- American people of German-Jewish descent

- American radio personalities

- Burials at Eden Memorial Park Cemetery

- California Democrats

- Comedians from Manhattan

- Deaths from pneumonia in California

- Jewish American male actors

- Jewish American comedians

- Jewish American musicians

- Jewish male comedians

- Male actors from Manhattan

- Marx Brothers

- People from the Upper East Side

- American vaudeville performers

- Jews from New York (state)

- Jewish film people